Neurochemical and inflammatory mechanisms in head and neck nerve injury: implications for neuromonitoring and neuroprotection

Article information

Abstract

Peripheral nerve injury in the head and neck region remains a critical cause of postoperative morbidity despite advances in microsurgery and intraoperative neuromonitoring. Beyond mechanical disruption, such injuries trigger complex neurochemical and inflammatory cascades that determine neuronal survival and functional recovery. This review synthesizes current evidence on the interplay between inflammatory signaling, oxidative stress, and neurotrophic modulation in peripheral nerve regeneration, emphasizing recurrent laryngeal and facial nerves. Experimental and molecular data reveal that Schwann cell–macrophage crosstalk, activation of NF-κB, MAPK, and PI3K/Akt pathways, and redox regulation via Nrf2 orchestrate the transition from degeneration to repair. Disruption of glutamatergic signaling, calcium homeostasis, and mitochondrial integrity further shapes the regenerative outcome. Translational research demonstrates that biomaterial scaffolds, photobiomodulation, and antioxidant or growth-factor therapies can enhance reinnervation, while clinical studies confirm that real-time electromyography monitoring predicts postoperative nerve function and reduces injury risk. Understanding these molecular–electrophysiological connections provides a foundation for developing predictive biomarkers and personalized neuroprotective strategies. The convergence of molecular neuroscience and precision surgery heralds a paradigm shift toward proactive, regenerative nerve care in head and neck surgery.

Introduction

Peripheral nerve injury (PNI) in the head and neck—especially damage to the recurrent laryngeal and facial nerves—remains a major source of postoperative morbidity, with large cohort data showing Recurrent laryngeal nerve (RLN) injury in ~6% of thyroid surgeries, underscoring the clinical impact in this region [1]. Beyond the immediate mechanical insult, accumulating evidence indicates that neuronal outcome is critically shaped by inflammatory cascades and the timing/quality of immune responses within the endoneurial milieu; appropriately tuned inflammation can facilitate axon regeneration and remyelination, whereas dysregulated signaling sustains damage [2].

Schwann cells (SCs) orchestrate much of this response by transitioning into a repair phenotype, coordinating debris clearance, guiding axonal regrowth, and modulating neurotrophic support—functions that are central to recovery in cranial-motor nerves as well [3]. A complementary dimension is redox biology: oxygen tension and reactive oxygen species (ROS) act as double-edged regulators—driving injury when excessive, yet providing essential signals for regeneration when controlled—implicating oxidative pathways as therapeutic targets during perioperative nerve protection [4]. Meanwhile, rapid advances in Schwann-cell–centered strategies (e.g., SC or SC-like cell therapies and microenvironmental modulation) are redefining translational opportunities to accelerate reinnervation and functional recovery [5].

The aim of this review is to integrate current knowledge on neurochemical alterations, inflammatory signaling, and redox regulation following PNI—particularly in the head and neck region—and to discuss how these mechanisms can inform intraoperative neuromonitoring (IONM) and molecularly targeted neuroprotective strategies for improved surgical outcomes.

Pathophysiology of Peripheral Nerve Injury

PNI triggers a cascade of inflammatory, oxidative, and neurotrophic events that together determine whether axonal regeneration or permanent degeneration ensues. Immediately after mechanical trauma—traction, compression, thermal, or ischemic insult—typical in head and neck surgeries involving the recurrent laryngeal or facial nerves, the distal nerve stump undergoes axonal and myelin disintegration, breakdown of the blood-nerve barrier, and infiltration of macrophages, while SCs in the area rapidly activate to initiate repair [6].

1. Wallerian degeneration

Wallerian degeneration (WD) represents a stereotyped sequence of events involving SC activation, macrophage recruitment, and up-regulation of cytokines and chemokines that coordinate debris clearance. This innate immune response removes inhibitory myelin remnants and generates a growth-permissive environment essential for regeneration [7]. The efficiency and timing of WD strongly influence functional recovery; delayed debris removal is associated with chronic inflammation and neuropathic pain.

2. Schwann cell “repair” phenotype

Upon axonal loss, mature SCs dedifferentiate into a “repair” phenotype, characterized by proliferation, alignment into Bands of Büngner, and secretion of trophic and extracellular-matrix molecules that guide regenerating axons. They simultaneously regulate inflammatory mediators and neurotrophic factors (nerve growth factor [NGF], brain-derived neurotrophic factor [BDNF], glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor [GDNF]), while reprogramming metabolism to support sustained regeneration [3].

3. Immune cell polarization and debris clearance

Recruited hematogenous macrophages cooperate with resident immune cells to phagocytose myelin and axonal debris. A well-timed polarization shift from pro-inflammatory M1 to pro-regenerative M2 phenotype is critical for restoring a permissive microenvironment. Failure to achieve this transition results in persistent cytokine production and fibrosis, delaying remyelination [8].

4. Molecular signaling interplay

Early activation of NF-κB and MAPK pathways drives the transcription of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin (IL)-1β, and IL-6, promoting immune recruitment but, when excessive, amplifying secondary axonal injury. In contrast, Nrf2 signaling induces antioxidant genes (heme oxygenase-1 [HO-1], superoxide dismutase, glutathione peroxidase [GPx]), mitigates oxidative stress, and promotes remyelination. Experimental deletion of Nrf2 impairs functional recovery, slows myelin debris clearance, and reduces axonal remyelination, confirming its protective role [9].

5. Implications for head and neck nerves

Although most mechanistic insights originate from limb nerve models, cranial motor nerves in the head and neck exhibit comparable pathophysiology under distinct anatomical constraints—shorter axonal length, denser motor units, and higher surgical exposure. Consequently, traction or thermal insults may trigger WD and inflammatory cascades more rapidly, narrowing the therapeutic window. Timely suppression of overactive NF-κB/MAPK signaling and concurrent activation of Nrf2- and PI3K/Akt-mediated neurotrophic pathways could therefore promote a transition toward regeneration-friendly conditions, offering molecular guidance for IONM and neuroprotective strategies.

Inflammatory Response after Nerve Injury

PNI evokes a highly coordinated inflammatory response that plays a dual role—facilitating debris clearance and regeneration when properly regulated, but exacerbating degeneration if excessive or prolonged. Immediately following trauma, SCs and resident macrophages in the endoneurial compartment secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6, which promote vascular permeability and recruit circulating immune cells [10]. These mediators initiate a transient inflammatory milieu necessary for WD and the removal of inhibitory myelin debris.

1. Macrophage recruitment and polarization

Within 48–72 hours after injury, monocyte-derived macrophages infiltrate the nerve and cooperate with SCs to phagocytose degenerated axons and myelin. The functional phenotype of these macrophages evolves dynamically—from a classically activated M1 phenotype, which produces nitric oxide and ROS, to an alternatively activated M2 phenotype, characterized by secretion of anti-inflammatory cytokines (IL-10, transforming growth factor-β [TGF-β]) and neurotrophic factors (NGF, BDNF). The temporal regulation of this M1–M2 switch determines the balance between chronic inflammation and regeneration [8,11]. Dysregulated polarization, as observed in metabolic or ischemic conditions, delays functional recovery.

2. Schwann cell–immune cell crosstalk

Activated SCs act as both inflammatory and reparative mediators. They release chemokines (CCL2, CXCL10) that guide macrophage infiltration and upregulate major histocompatibility complex (MHC II) molecules, allowing limited antigen presentation in the injured nerve microenvironment. Concurrently, SCs secrete neurotrophic and extracellular-matrix molecules that direct axonal regrowth. Recent transcriptomic analyses reveal that SC–macrophage communication via NF-κB, MAPK, and JAK/STAT pathways orchestrates the transition from degeneration to regeneration [12].

3. Molecular signaling pathways

Inflammatory cascades are initiated primarily through NF-κB and MAPK activation, which regulate transcription of cytokines, adhesion molecules, and oxidative enzymes. These pro-inflammatory pathways are counterbalanced by Nrf2-dependent antioxidant responses that limit oxidative stress. The precise coordination between these signaling systems determines the outcome of the inflammatory phase. Excessive NF-κB activity leads to SC apoptosis and persistent demyelination, whereas timely Nrf2 activation promotes remyelination and resolution of inflammation [2].

4. Resolution and regenerative transition

As regeneration progresses, pro-inflammatory cytokine expression subsides, and M2 macrophages dominate, secreting IL-10, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and TGF-β to promote angiogenesis and matrix remodeling. SCs revert to a differentiated myelinating phenotype, restoring nerve conduction. However, incomplete resolution can lead to fibrosis and neuroma formation. Understanding these time-dependent inflammatory dynamics is particularly relevant to head and neck nerves such as the recurrent laryngeal and facial nerves, where intraoperative traction or thermal stress may trigger molecular inflammation even without visible structural damage.

Neurochemical Alterations after Peripheral Nerve Injury

PNI induces a complex series of neurochemical alterations that modulate neuronal excitability, axonal degeneration, and SC function. These alterations involve dysregulation of glutamate signaling, oxidative stress, ionic imbalance, and mitochondrial dysfunction, ultimately influencing whether regeneration or chronic neuropathy ensues.

1. Glutamatergic signaling and excitotoxicity

Glutamate, the predominant excitatory neurotransmitter in the nervous system, is also active within the peripheral nervous system. After nerve injury, increased extracellular glutamate activates ionotropic receptors (AMPA, NMDA, kainate) and metabotropic receptors expressed on SCs and sensory neurons [13]. Overactivation of these receptors promotes intracellular calcium influx and excitotoxicity, thereby disrupting myelin stability and axonal metabolism. SCs themselves respond to glutamate through specific receptor signaling cascades that regulate proliferation and differentiation, suggesting that controlled glutamatergic signaling contributes to regeneration rather than degeneration [14].

2. Schwann cell metabolic regulation

SCs are metabolically active and undergo extensive reprogramming after injury. One key mechanism involves the regulation of glutamine synthetase (GS), which converts glutamate to glutamine. Proteasomal degradation of GS in injured SCs reduces glutamate detoxification capacity, altering the balance between excitatory and inhibitory signaling within the microenvironment. Restoration of GS expression supports remyelination and SC redifferentiation [15]. These findings reveal a molecular link between neurotransmitter homeostasis and glial differentiation during nerve repair.

3. Calcium dysregulation and mitochondrial dysfunction

Excessive calcium influx is a hallmark of neurochemical disruption following axonal injury. After trauma, the release of calcium from intra-axonal endoplasmic reticulum stores triggers mitochondrial overload, leading to depolarization, energy depletion, and activation of proteolytic enzymes such as calpains [16]. The resulting mitochondrial dysfunction not only initiates axonal fragmentation but also amplifies oxidative stress, forming a self-perpetuating degenerative loop. Stabilizing calcium homeostasis is therefore considered a key strategy to limit secondary degeneration.

4. Oxidative stress and redox imbalance

ROS are produced both by mitochondrial dysfunction and enzymatic sources during nerve injury. Although physiological ROS levels participate in regeneration signaling, excessive accumulation damages lipids, proteins, and DNA. Experimental data demonstrate that controlled oxygen tension and balanced ROS signaling are essential for axonal regrowth and remyelination. Excessive oxidative stress, however, impairs SC proliferation and delays [4]. Thus, maintaining redox equilibrium is a critical determinant of successful recovery.

5. Integrated neurochemical landscape

Collectively, these studies highlight that neurochemical alterations after PNI are not passive consequences but active determinants of regeneration. Interventions that modulate glutamate metabolism, calcium buffering, and oxidative stress can shift the injured nerve from a degenerative to a regenerative trajectory. A deeper understanding of these intertwined biochemical pathways will support the development of targeted molecular therapies and intraoperative neuroprotective strategies for cranial and peripheral nerves in the head and neck region.

Molecular Crosstalk between Inflammation and Neuroregeneration

Peripheral nerve regeneration is not merely a structural process but a tightly coordinated molecular dialogue between inflammatory, oxidative, and trophic signaling pathways. The transition from degeneration to regeneration requires the timely suppression of excessive inflammation and activation of intracellular cascades that promote SC survival, axonal elongation, and remyelination.

1. Inflammatory signaling as a double-edged regulator

Inflammation after PNI serves both protective and destructive roles. Activated macrophages and SCs release cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6, which initiate debris clearance and recruit additional immune cells. However, prolonged activation of NF-κ B and MAPK pathways can extend the inflammatory phase, leading to secondary axonal damage. Recent analyses have emphasized that balanced inflammatory signaling is essential for transitioning toward a regenerative phase [2].

2. Growth factors and intracellular signaling cascades

Following the resolution of acute inflammation, growth factors including NGF, BDNF, fibroblast growth factors (FGFs), and VEGF orchestrate neuronal survival and axonal outgrowth. These molecules activate the PI3K/Akt and ERK/MAPK pathways in both neurons and SCs, enhancing cell survival and myelin repair [17]. Among these, Akt plays a particularly critical role in suppressing apoptotic signaling while facilitating regeneration in vivo [18].

3. Redox modulation and regenerative transition

Oxidative stress is a key mediator linking inflammation and regeneration. Low-to-moderate levels of ROS serve as signaling molecules that stimulate neurotrophic pathways and angiogenesis, whereas excessive ROS accumulation impairs SC proliferation and axonal growth. The redox-sensitive transcription factor Nrf2 counteracts oxidative stress by upregulating antioxidant enzymes such as HO-1 and GPx, promoting the resolution of inflammation and tissue repair [4]. Thus, precise modulation of ROS levels appears fundamental to sustaining the regenerative phase.

4. Integration of PI3K/Akt signaling with oxidative control

Experimental evidence shows that the PI3K/Akt pathway not only promotes neuronal survival but also reduces oxidative damage by attenuating mitochondrial dysfunction and enhancing Nrf2 activity. Administration of FGF10, for instance, enhances peripheral nerve regeneration through activation of the PI3K/Akt axis and concomitant reduction in ROS generation [19]. These findings reveal an interdependent relationship in which trophic factor signaling, redox homeostasis, and inflammatory resolution collectively determine regenerative success.

5. Translational implications for head and neck nerves

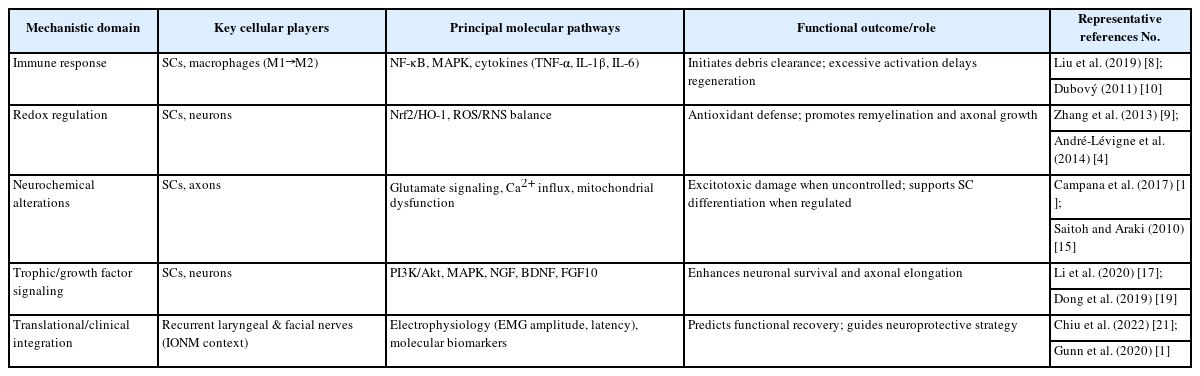

In the head and neck region, where recurrent laryngeal and facial nerves are particularly vulnerable to surgical injury, understanding this molecular crosstalk is vital. The temporal coordination between NF-κB–mediated inflammation, PI3K/Akt–driven survival signaling, and Nrf2-regulated oxidative defense may guide perioperative strategies for neuroprotection. Pharmacological agents or biomaterials designed to fine-tune these pathways could enhance outcomes in reconstructive or oncologic procedures involving cranial and peripheral nerves. A summary of the key molecular and cellular mechanisms linking inflammation, oxidative stress, and neuroregeneration is provided in Table 1.

Experimental and Translational Insights in Head and Neck Nerve Injury

Experimental and translational models have played a crucial role in elucidating the mechanisms of PNI and recovery within the head and neck region. These studies bridge the gap between fundamental neurobiology and clinical applications such as IONM, nerve grafting, and photobiomodulation (PBM) therapy.

1. Animal models of recurrent laryngeal nerve injury

The RLN serves as one of the most frequently injured cranial-motor nerves during thyroid and paratracheal surgeries. Preclinical studies using rat RLN transection and traction models have revealed distinct electrophysiological and histologic patterns of injury and recovery. In the rat model developed by Tessema et al. [20], compound muscle action potentials progressively improved over weeks, paralleling reinnervation and axonal regeneration observed histologically. These findings established a foundation for assessing therapeutic interventions and the timing of nerve recovery.

2. Functional monitoring and clinical correlation

Translational advances in IONM have significantly improved nerve preservation during head and neck procedures. Continuous electromyography (EMG) monitoring allows for real-time identification of amplitude reduction and latency prolongation, indicators of traction-induced neuropraxia. A prospective study by Chiu et al. [21] demonstrated that specific EMG recovery patterns correlated with postoperative vocal fold mobility, providing evidence that intraoperative amplitude recovery predicts functional outcomes. Moreover, a meta-analysis by Zheng et al. [22] confirmed that the use of IONM significantly reduces the incidence of RLN palsy compared with visual identification alone, emphasizing its role as both a diagnostic and preventive tool.

3. Biomaterial and molecular strategies for nerve repair

Recent bioengineering approaches have focused on enhancing RLN regeneration through scaffolds and molecular modulation. In an experimental rat model [23] demonstrated that a collagen conduit loaded with laminin and laminin-binding neurotrophic factors (BDNF and GDNF) improved axonal regeneration and restored muscle reinnervation. This combinatorial approach represents a promising platform for cranial-motor nerve reconstruction, particularly in cases of transection or segmental loss.

4. Photobiomodulation and regenerative enhancement

PBM using low-level laser or light-emitting diode (LED) sources has emerged as a noninvasive strategy to augment nerve recovery. Er-Rouassi et al. [24] reported that LED irradiation after facial nerve section–suture in rats significantly accelerated axonal regeneration and improved functional recovery. The study demonstrated enhanced myelination and reduced fibrosis, likely through modulation of oxidative stress and mitochondrial activity. These data provide a rationale for incorporating PBM as an adjunct to microsurgical repair or postoperative rehabilitation in head and neck nerve injuries.

5. Translational outlook

Collectively, animal and clinical evidence suggest that successful regeneration depends on the integration of structural, electrophysiological, and molecular factors. Experimental models have clarified how electrophysiologic monitoring, biomaterial scaffolds, and PBM can synergistically improve outcomes. For head and neck surgery, especially thyroidectomy and parotidectomy, a multidisciplinary approach combining precise IONM, optimized microenvironmental repair, and molecularly guided neuroprotection may represent the future standard for nerve preservation and recovery.

Clinical Implications for Head and Neck Surgery

The integration of electrophysiologic monitoring and molecular neurobiology has reshaped the surgical management of head and neck nerve injuries. In thyroid and paratracheal procedures, real-time assessment of RLN function using IONM provides both diagnostic and prognostic information, enabling safer dissection and more accurate prediction of postoperative outcomes.

1. Incidence and risk stratification

Large clinical datasets have underscored the continuing relevance of RLN injury as a major source of postoperative morbidity. In a multicenter review of 11,370 thyroidectomies, Gunn et al. [1] reported RLN injury in approximately 6% of cases, highlighting risk factors such as malignancy, reoperation, and anatomic variation. Early identification of vulnerable cases allows stratification of surgical risk and appropriate use of neuromonitoring technologies.

2. Intraoperative neuromonitoring and surgical decision-making

Continuous IONM enables real-time detection of signal loss or amplitude reduction, allowing for staged or limited surgery on the contralateral side when necessary. The International Neural Monitoring Study Group (INMSG) recommends staging bilateral thyroid surgery upon loss of signal on the first side, to prevent bilateral paralysis [25]. This “staged thyroidectomy” approach has significantly reduced permanent RLN palsy rates worldwide and represents a benchmark in endocrine surgical safety. These recommendations, established by the INMSG, remain the reference standard for bilateral staging after loss of signal and integrate surgical–laryngeal–electrophysiologic data for invasive disease.

For invasive thyroid cancer, the same group emphasized that appropriate preoperative imaging and meticulous dissection guided by IONM improve oncologic control while minimizing functional deficits [26]. These guidelines integrate molecular and electrophysiological perspectives, reflecting a new standard of precision surgery.

3. Evidence from systematic and prospective studies

Meta-analytic evidence supports the protective value of neuromonitoring. In a pooled analysis of over 25 studies, Zheng et al. [22] demonstrated that IONM significantly lowers both transient and permanent RLN palsy rates compared with visual identification alone. The benefit was most pronounced in high-risk procedures, confirming the role of IONM as an essential adjunct rather than a purely diagnostic tool.

Recent clinical data further show that intraoperative EMG recovery patterns can predict postoperative nerve function. Chiu et al. [21] observed that immediate or early EMG amplitude recovery following traction-related signal loss correlated with normal vocal fold motion at follow-up. This real-time physiologic feedback enables dynamic intraoperative decision-making and prognostication.

4. Translational perspective

The convergence of electrophysiologic monitoring, molecular insight, and surgical strategy underscores a translational paradigm: nerve injury prevention is most effective when intraoperative detection, physiologic recovery assessment, and postoperative neurochemical modulation are integrated. Understanding how inflammation, oxidative stress, and neurotrophic signaling affect EMG recovery may allow development of perioperative neuroprotective interventions— linking laboratory discovery directly to clinical practice.

Conclusion

PNI in the head and neck region embodies the intersection of clinical precision and fundamental neurobiology. Beyond mechanical disruption, these injuries initiate complex cascades of neurochemical and inflammatory responses that ultimately determine functional recovery. Accumulating evidence from molecular and electrophysiologic studies demonstrates that inflammatory mediators, oxidative stress, and glutamatergic signaling profoundly influence SC plasticity, axonal regeneration, and neuronal survival.

The sections of this review collectively highlight that post-injury neurochemistry functions not as a passive consequence but as an active determinant of regeneration. SC–macrophage interactions, redox homeostasis mediated by Nrf2, and trophic signaling via PI3K/Akt and MAPK pathways orchestrate the transition from degeneration to repair. Translational and experimental advances—including biomaterial scaffolds, PBM, and targeted delivery of neurotrophic factors—further demonstrate that modulation of these molecular networks can enhance reinnervation and functional restoration.

Clinically, the integration of IONM with this biological insight has transformed nerve management in thyroid and head-and-neck surgery. Real-time electrophysiologic feedback not only prevents iatrogenic injury but also reflects the underlying molecular state of neural recovery, offering a bridge between basic science and surgical application.

Future directions should emphasize biochemical and electrophysiologic biomarkers capable of predicting nerve recovery and guiding personalized neuroprotective strategies. Advances in molecular imaging, bioelectronic monitoring, and machine-learning analysis of IONM data may soon enable proactive rather than reactive nerve preservation. Ultimately, the convergence of molecular neuroscience and precision surgery holds promise for establishing a new paradigm of predictive, regenerative nerve care in head and neck surgery.

Notes

Funding

None.

Conflict of Interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Data Availability

None.

Author Contributions

All work was done by HSR.