Evoked potential-based sensory monitoring in chronic itch: toward objective assessment of neural hyperexcitability

Article information

Abstract

Chronic itch is a neuro–immune disorder in which inflammatory cytokines and neurotrophic factors drive sensory hyperexcitability across peripheral and central pathways. Persistent inflammation sensitizes C- and Aδ-fibers, alters conduction properties, and disrupts inhibitory circuits within the spinal cord and cortex, ultimately producing central sensitization. Despite these well-characterized neurophysiologic alterations, clinical assessment continues to rely on subjective scales such as the visual analogue scale and numerical rating scale, highlighting the lack of objective biomarkers. Evoked potentials (EPs), which reflect cortical responses within hundreds of milliseconds after sensory stimulation, provide quantitative measures of latency and amplitude that correspond to conduction velocity and cortical synchrony. In chronic inflammatory itch, prolonged N₂–P₂ latency and reduced amplitude have been consistently reported, indicating impaired sensory conduction and heightened central excitability. This review synthesizes current insights into inflammation-induced neural sensitization, explains EP principles and fiber-specific activation patterns, and evaluates the potential of integrating electroencephalography and EPs for clinical assessment. Overall, accumulating evidence supports EPs as a noninvasive biomarker for visualizing sensory hyperexcitability in chronic itch and underscores their promise in establishing evoked potential–based sensory monitoring as an objective framework for evaluating sensory neural function.

Introduction

Pruritus is a common sensory symptom across all age groups, and when it persists for more than 6 weeks, it is classified as chronic itch. Chronic itch is accompanied by sleep disturbance and functional impairment, markedly reducing quality of life [1]. In population-based studies, the lifetime prevalence has been reported as approximately 22%, the 12-month prevalence as 16.4%, and the cumulative prevalence as 7% [2]. Epidemiologic data from the United States indicate that itch accounts for approximately seven million outpatient visits each year, with particularly high prevalence among the elderly and in patients with chronic inflammatory diseases [1].

Nevertheless, standard clinical evaluation in practice still depends on patient-reported scales. The visual analogue scale (VAS) and numerical rating scale (NRS) are the most widely used tools, but their results vary substantially according to patient perception and situational factors, making objective comparison difficult [3]. Consequently, itch remains a universal yet unquantified sensory phenomenon. To complement these limitations, functional assessments such as quantitative sensory testing (QST), nerve conduction studies, and evoked potentials (EPs) have been proposed, although their application has so far been restricted to research or special cases [4].

In chronic inflammatory diseases such as atopic dermatitis (AD), psoriasis, and chronic kidney disease (CKD), itch often extends beyond superficial skin inflammation to involve functional changes in the peripheral and central nervous systems. In these disorders, inflammatory cytokines and activated immune cells increase the sensitivity of sensory fibers, disturb the balance of opioid receptor activity, or induce small-fiber neuropathy [1]. This inflammation-induced alteration of neural function defines the concept of neuropathic itch, in which injury or hyperexcitability of C- and Aδ-fibers, together with central sensitization within the spinal cord and brain, contributes to the persistence of pruritus. Thus, chronic inflammatory itch should be understood not merely as a dermatologic condition but as a complex neurogenic disorder combining sensory hyperexcitability and central sensitization [4].

Despite this, objective biomarkers or electrophysiologic indicators that can quantify itch intensity, neural alterations, or therapeutic response are nearly absent. Most clinical assessments still rely on subjective self-report measures such as the VAS or NRS. Although these scales are convenient, their outcomes fluctuate according to cognitive, emotional, and environmental factors and show inconsistent correlations with actual scratching behavior (actigraphy) or neural responses [5]. Consequently, there are persistent limitations in quantitatively comparing therapeutic effects or objectively characterizing neuropathic changes. The development of an objective, clinically applicable assessment tool remains an urgent unmet need in both research and practical medicine.

Against this background, the present review explores the potential of EPs as an objective method for evaluating the presence and progression of neuropathic itch in chronic inflammatory conditions. Specifically, EPs record neural and cortical electrical responses to pruritic stimuli transmitted through C- and Aδ-fibers, thereby providing a possible bridge between sensory neurophysiology and clinical monitoring. Following this introduction, the paper is organized into the following structure: pathophysiology, principles of EP measurement, clinical evidence, and the applicability of EP-based sensory monitoring and future perspectives.

The literature reviewed in this work was identified through searches conducted in PubMed and Scopus databases between January 1990 and May 2024 using the keywords “chronic itch,” “pruritus,” “evoked potential,” “LEP,” and “CHEP.” Only peer-reviewed English-language studies investigating electrophysiologic assessment of chronic pruritus in humans were included.

Pathophysiology: From Inflammation to Neural Sensitization

1. Peripheral sensitization

Chronic inflammatory skin is not merely an outer barrier but a neuro-immune interface in which immune, epithelial, and neural signaling intersect. During this process, inflammatory cytokines enhance the excitability of sensory neurons and induce peripheral sensitization [6].

Interleukin (IL)-4 and IL-13 activate IL-4Rα/IL-13R α1 receptors on sensory neurons to trigger JAK1-dependent neuronal sensitization, while IL-31 stimulates IL-31Rα/OSMRβ pathways to increase the activity of TRPV1- and TRPA1-positive dorsal root ganglion neurons [6,7]. These type 2 cytokines lower the threshold for itch signal transmission and sustain excitability even through non-histaminergic pathways [6].

At the epidermal level, the nerve growth factor (NGF)-TrkA axis promotes nerve fiber outgrowth, while imbalance of Sema3A fails to suppress it, resulting in increased intraepidermal nerve density [8,9]. This correlates with the hyperinnervation and itch intensity observed in AD lesions [9]. Activated keratinocytes also release thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP) following PAR2 and TRPV3 stimulation, and this TSLP acts on neuronal TSLP receptor to establish a self-amplifying skin-nerve excitatory loop [10]. In addition, mechanical stress or inflammatory conditions lead keratinocytes to release adenosine triphosphate (ATP), which activates P2Y2 receptors on adjacent neurons and induces Ca2+ waves [11].

Altogether, the interactions among IL-4, IL-13, IL-31, NGF, TSLP, and ATP reorganize the cutaneous sensory network, forming a pathophysiologic basis in which skin inflammation is directly linked to C- and Aδ-fiber hyperexcitability.

2. Central sensitization

When peripheral stimulation persists, the inhibitory circuits within the spinal dorsal horn (GABA, glycine) gradually weaken, while excitatory neurotransmission via glutamate, substance P, and calcitonin gene-related peptide increases [12]. This imbalance produces long-term potentiation of excitatory synapses, resulting in hyperactivation of wide-dynamic-range neurons and gastrin-releasing peptide receptor (GRPR) interneurons [13]. The GRPR circuit specifically amplifies pruritic signals originating from C-fiber input, while the loss of Bhlhb5+ inhibitory interneurons further stabilizes the sensitized state [12,13].

Activated spinal neurons transmit signals through the spinothalamic tract to the thalamus, which then projects to the somatosensory cortex (S1/S2) and insula to mediate the sensory and affective dimensions of itch [14]. This pathway partly overlaps with the pain transmission system, and in chronic conditions, inputs for pain and itch can mutually facilitate each other—a phenomenon known as cross-facilitation [13]. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies have demonstrated abnormally enhanced connectivity among the thalamus, insula, and prefrontal cortex, together with reduced activation thresholds in sensory cortical regions (S1/S2), indicating cortical sensitization [14,15].

Ultimately, the collapse of inhibitory mechanisms and persistent excitation across the peripheral–spinal–cortical continuum creates an “itch–pain continuum,” where the boundaries between the two sensory modalities become blurred.

3. Systemic integration

In summary, chronic inflammation extends beyond a local cutaneous reaction to induce a systemic hyperexcitable neural state. Cytokine-neurotransmitter interactions alter the conduction properties of sensory neurons and weaken spinal and cortical inhibitory circuits, thereby stabilizing central sensitization [16]. The collapse of these inhibitory networks and enhancement of excitatory signaling form a pathophysiologic continuum in which cutaneous stimulation is excessively amplified at the cortical level.

During this process, the electrophysiologic responses of the brain and spinal cord—such as EPs and motor evoked potentials (MEPs)—exhibit alterations in latency and amplitude under inflammatory or metabolic conditions, providing objective visualization of the nervous system’s hyperexcitable state [17]. As a result, chronic inflammatory itch can be conceptualized as a neural sensitization disorder that transcends the skin, reflecting system-wide alterations in neuro-immune interactions.

Evoked Potentials: Principles and Measurement

1. Basic concept

EPs are electrophysiologic techniques that quantitatively record the brain’s electrical responses to external stimuli such as thermal, electrical, mechanical, or visual inputs [18,19]. Voltage changes occurring within several hundred milliseconds after stimulation are extracted from electroencephalographic (electroencephalography, EEG) signals, and by analyzing latency and amplitude, the conduction speed and response strength of sensory transmission can be evaluated [20,21].

Latency reflects the conduction time required for a stimulus to travel from peripheral receptors to the cerebral cortex, whereas amplitude represents the strength of the response or the number of activated nerve fibers [22]. In particular, the magnitude and temporal characteristics of the cortical N2–P2 complex show a linear correlation with stimulus intensity and perceived pain, and such waveform changes directly reflect the excitability and sensitivity of the nervous system to stimulation [23].

Clinically, EP parameters are utilized as objective indicators for detecting functional changes in peripheral nerves. For instance, in patients with diabetic small-fiber neuropathy, a decrease in N2–P2 amplitude and a delay in latency have been observed, suggesting impaired conduction in C- and Aδ-fibers. Moreover, in small-fiber neuropathy cohorts, laser-evoked potentials (LEPs) show a significant correlation with intraepidermal nerve fiber density obtained from skin biopsy, demonstrating approximately 80% sensitivity and over 80% specificity [24].

Therefore, analysis of EP latency and amplitude enables an integrated functional evaluation of both peripheral and central sensory pathways and serves as a major neurophysiologic index reflecting the functional state of C- and Aδ-fibers [25]. Consequently, when sensory fibers are damaged or become hyperexcitable due to inflammation, characteristic waveform changes—such as latency prolongation and amplitude reduction—are typically observed.

2. Fiber-specific evoked potential responses

Peripheral sensory fibers that respond to external stimuli are primarily classified into C-fibers and Aδ-fibers, each differing distinctly in stimulus type, conduction velocity, and cortical potential characteristics [25].

C-fibers are unmyelinated small fibers with extremely slow conduction velocities ranging from 0.5–2 m/sec, and they are involved in continuous and diffuse sensations such as itch, heat, and dull pain. These fibers are activated through receptors such as TRPV1, TRPA1, and PAR2, and they generate ultra-late cortical potentials that arrive slowly at the cortex [25]. EPs originating from C-fibers generally exhibit low-amplitude potentials occurring several hundred milliseconds after stimulation (approximately 700–1,200 msec) and tend to be modulated more by stimulus duration and attention than by stimulus intensity.

In contrast, Aδ-fibers are thinly myelinated fibers with conduction velocities of 4–30 m/sec, primarily responding to sharp pain or rapid heat stimuli [25]. The N2–P2 complex elicited by LEPs or contact heat-evoked potentials (CHEPs) reflects the activity of these Aδ-fibers and typically appears 200–400 ms after stimulation [23,25]. Intracortical recording studies have demonstrated that the amplitudes of N2 and P2 components increase linearly with stimulus intensity, indicating that these components represent the degree of Aδ-fiber excitation and the cortical synchrony of sensory processing [23].

Furthermore, CHEPs—which stimulate both Aδ-fibers and mixed C/Aδ-fiber populations—exhibit systematic variations in latency and amplitude depending on the stimulation site (e.g., hand, foot, or face). With advancing age, CHEP latency becomes prolonged and amplitude decreases, reflecting either fiber dysfunction or conduction delay related to demyelination [24].

Taken together, C-fibers reflect slow and persistent itch or pain stimuli, while Aδ-fibers respond rapidly to intense, sharp sensations. Thus, the early N2–P2 complex of EP waveforms primarily represents Aδ-fiber activity, whereas the ultra-late components correspond to C-fiber responses. Integrative analysis of these two components allows objective evaluation of functional changes in peripheral sensory fibers and conduction impairments resulting from inflammation or demyelination.

3. Measurement principles and interpretation

EPs are electrophysiologic techniques that quantitatively evaluate the central nervous system’s responses to peripheral stimulation. Under controlled stimulus conditions, they are used to analyze the temporal and spatial dynamics of neural pathway activity. EP measurement generally consists of three stages: stimulation, recording, and signal analysis [18,21].

1) Stimulation phase

EPs can be elicited by thermal, electrical, or mechanical stimuli, and depending on the characteristics of the stimulus, specific sensory fibers such as Aδ- or C-fibers are selectively activated. In pruritus and pain research, CO2 or Thulium:YAG laser stimulation (LEP) and contact thermode stimulation (CHEP) are most commonly used [25]. These stimuli activate both myelinated and unmyelinated peripheral fibers to induce sensory input, and factors such as stimulus intensity, duration, and interstimulus interval critically determine reproducibility and accuracy.

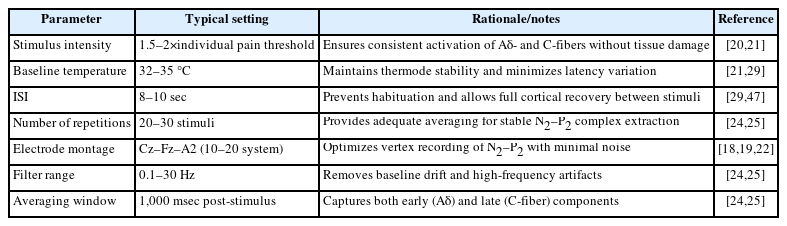

Accordingly, the International Federation of Clinical Neurophysiology recommends standardized parameters for stimulus intensity, frequency, and interval to minimize inter-experimental variability [21]. Based on normative studies, under identical stimulation conditions, the latency and amplitude of the N2–P2 complex are stably reproducible, supporting the validity of EPs as objective and quantitative tools [20,24].

2) Recording phase

Recordings are typically conducted according to the international 10–20 electrode placement system, where the Cz–Fz–A2 configuration yields the most distinct cortical responses [18,19]. EEG signals are filtered within the 0.1–300 Hz range, and averaging of 20–100 stimuli removes background EEG noise, isolating the stimulus-related potentials.

The representative waveform, the N2–P2 complex, primarily reflects synchronous excitation within the secondary somatosensory cortex (SII) and insula [23,25]. Intracortical electrode studies have shown that the amplitudes of N2 and P2 increase linearly with stimulus intensity, while latency remains unaffected by changes in stimulus strength [23]. This finding indicates that latency reflects the conduction velocity between peripheral and central structures, whereas amplitude represents the synchrony and recruitment of cortical neuronal activity.

3) Signal analysis

EP analysis mainly focuses on three quantitative indices: latency, amplitude, and waveform morphology. The latency, defined as the interval from stimulus onset to the appearance of specific components (N1, N2, P2), reflects the conduction velocity and structural integrity of the sensory pathway [19,24]. In cases of peripheral nerve injury or demyelination, latency prolongation is a characteristic finding [24].

The amplitude represents the number of activated sensory fibers and the degree of cortical synchrony. A decrease in N2–P2 amplitude indicates weakened sensory input or cortical hypoexcitability, while proportional increases in amplitude with greater stimulus intensity suggest normal cortical responsiveness [23,25].

Finally, waveform morphology evaluates the spatial distribution of cortical responses. In healthy individuals, a distinct biphasic N2–P2 waveform appears at the vertex, whereas in pathological conditions, the waveform becomes attenuated or delayed [25].

4) Interpretive considerations

In pathologic conditions such as chronic itch, diabetic neuropathy, or inflammatory skin diseases, consistent findings of N2–P2 latency prolongation and amplitude reduction have been reported [24,25]. These alterations are interpreted as reflecting either impaired peripheral sensory conduction or neural hyperexcitability caused by central sensitization. In addition, latency prolongation and amplitude reduction associated with aging suggest that EPs sensitively reflect both structural and functional alterations within peripheral and central sensory pathways [24].

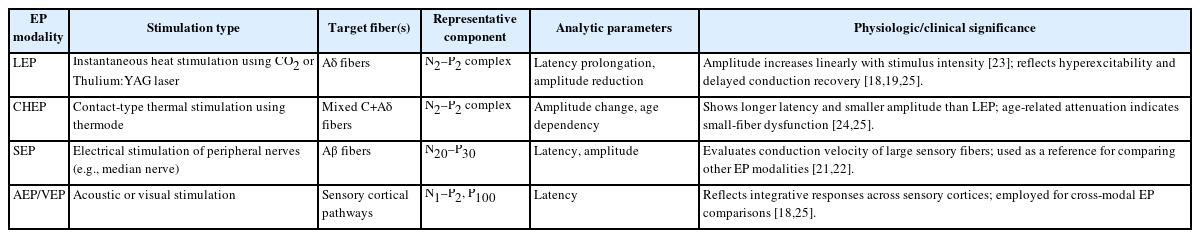

Therefore, EPs serve as a noninvasive neurophysiologic technique that allows temporal and quantitative visualization of central responses to sensory stimulation. They provide a useful tool for objectively evaluating abnormalities in neural transmission and sensory hyperexcitability in chronic itch and pain-related disorders (Table 1).

Electroencephalography–Evoked Potential Interpretation and Expansion of Clinical Monitoring in Chronic Itch

As described in the previous section, EPs provide a quantitative electrophysiologic measure of the nervous system’s responses to sensory stimuli, objectively visualizing the functional integrity of the peripheral–central sensory circuit. In particular, EEG-based EP analysis enables real-time tracking of the temporal sequence and intensity of cortical responses to sensory input. This capability has made EEG–EP analysis an emerging core method for investigating cortical sensitization in sensory hyperexcitability disorders such as chronic itch.

This section reviews the characteristic EP alterations observed in patients with chronic itch and discusses their underlying neurophysiologic implications. Furthermore, it explores the potential for EEG–EP technology to evolve into a clinical sensory-nerve monitoring tool comparable to intraoperative neuromonitoring (IONM). Through this perspective, EPs are proposed not only as research-grade neurophysiologic indicators but also as objective biomarkers of sensory hyperexcitability, paving the way for their development into practical, real-time clinical monitoring instruments.

1. Integrated electroencephalography– evoked potential analysis for elucidating the electrophysiologic mechanisms of chronic itch

As described above, EPs serve as quantitative indicators that evaluate functional changes in neural conduction and cortical responses by recording the temporal sequence of the central nervous system’s electrical reactions to sensory stimuli. EPs are fundamentally derived from EEG signals, and by isolating only the response components that are synchronized in time with the stimulus, they allow analysis of the temporal and spatial dynamics of cortical responses to sensory input [26,27].

In other words, while EEG reflects the overall electrical activity of the brain, EPs specifically visualize the cortical selectivity of responses evoked by particular stimuli. This characteristic enables quantitative assessment of pathway integrity, temporal delays in sensory processing, and changes in neural activity occurring during stimulus processing [27,28].

For example, in thermal-stimulation paradigms, a stable N2–P2 complex originating from the somatosensory cortex is typically observed between 300–500 msec after stimulation, representing the temporal transmission of nociceptive signals via Aδ-fibers to the cerebral cortex [29-31]. The N2 component primarily reflects the onset of nociceptive perception, whereas the P2 component corresponds to late cortical processing associated with intensity coding [26,29]. Moreover, the latency of this complex indicates conduction velocity and cortical integration speed, while the amplitude represents the synchrony and recruitment of neuronal populations [27,28]. Thus, prolonged latency or reduced amplitude may suggest functional deterioration of peripheral-to-central sensory transmission or an abnormal inhibitory state at the cortical level.

Recent EEG–EP hybrid analyses have extended beyond simple potential recording to delineate the temporal activation patterns of cortical networks in response to sensory stimuli [26,27]. For instance, combining phase-locking analysis of EEG with simultaneous EP waveform interpretation allows real-time tracking of cortical information flow and its pathologic alterations. This integrative approach has contributed to the quantitative assessment of cortical reorganization and abnormal synchronization of neural circuits in sensory hyperexcitability disorders such as chronic pain and chronic itch [28].

Consequently, integrated analysis of EEG and EP data represents a high–temporal-resolution neurophysiologic tool that enables simultaneous interpretation of both the temporal sequence and cortical activation dynamics of sensory processing. By precisely capturing minute transmission delays, variations in conduction velocity, and dynamic patterns of cortical activity, this approach plays an essential role not only in the evaluation of sensory nerve function but also in elucidating the mechanisms underlying pathophysiologic central sensitization.

2. Evoked potential alterations in patients with chronic itch

EPs reflect not only the functional integrity of sensory pathways but also the degree of hyperexcitability under pathologic conditions [32]. Recent studies have demonstrated that in patients with chronic pruritus, persistent skin inflammation and continuous peripheral stimulation induce functional reorganization of the somatosensory cortex, which can be electrophysiologically visualized through EP analysis [32-34].

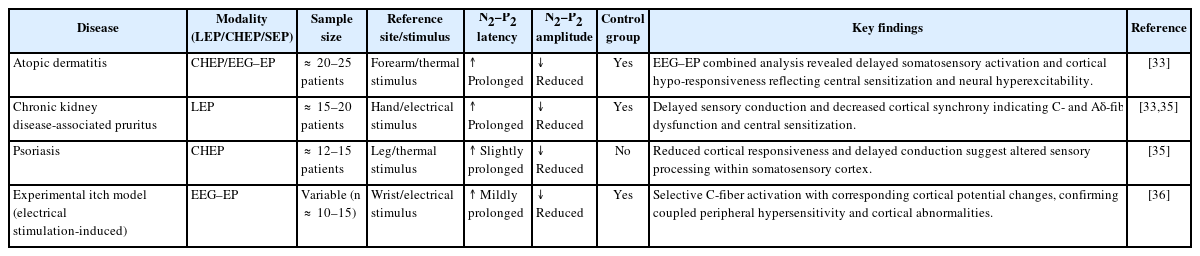

In various chronic inflammatory skin disorders such as AD, CKD-associated pruritus (CKD-pruritus), and psoriasis, EP waveforms elicited by thermal or electrical stimuli consistently show prolonged latency and reduced amplitude, reflecting delayed sensory conduction and decreased neural synchrony [33,35]. In particular, EEG–EP combined studies in AD patients have revealed reduced spatial activation and temporal delays in somatosensory cortical responses to thermal stimuli, indicating a state of cortical sensitization associated with neural hyperexcitability [33].

Similarly, EP analyses in patients with chronic itch have demonstrated decreased N2–P2 amplitude and prolonged latency in response to both nociceptive and pruritic stimuli. These findings are interpreted as electrophysiologic indicators of C- and Aδ-fiber dysfunction and central sensitization [35]. Moreover, studies combining QST with EP measurements have shown that higher thermal or mechanical thresholds are associated with lower EP amplitudes, suggesting that skin sensory thresholds and cortical response magnitudes are interrelated [36].

Furthermore, experimental models using electrical stimulation-induced itch have confirmed selective activation of C-fibers and corresponding changes in cortical potentials through EEG analysis, providing direct evidence that EPs simultaneously reflect both peripheral sensory hypersensitivity and cortical functional abnormalities [36]. Collectively, these findings suggest that EPs hold high clinical potential as a noninvasive electrophysiologic tool for objectively assessing sensory neural excitability in patients with chronic itch (Table 2, 3).

3. Clinical applicability of evoked potential-based neural monitoring for assessing therapeutic response in chronic itch

EP technology was originally developed for IONM to prevent neural injury during surgery and has been widely used in clinical practice [37,38]. IONM records sensory or MEP in real time along neural pathways, allowing early detection of functional impairment caused by stimulation, ischemia, or mechanical compression during surgery [37,39]. In this process, somatosensory evoked potentials (SEPs) and MEPs serve as the principal indicators for assessing the integrity of sensory and motor pathways, respectively. By analyzing changes in latency and amplitude, these techniques quantitatively determine the occurrence of neural injury [38,40]. Specifically, SEPs reflect abnormalities in the dorsal column–medial lemniscus pathway, whereas MEPs directly indicate functional disruption of the corticospinal tract. Thus, IONM represents a cornerstone of real-time intraoperative neurophysiologic monitoring that minimizes neural injury risk and significantly enhances patient safety through continuous feedback during surgery [37-40].

However, in sensory hyperexcitability disorders such as chronic itch, an analogous objective, real-time evaluation system has yet to be established. In current clinical settings, itch intensity is typically assessed using subjective self-reported scales such as the VAS, NRS, or 5-D itch scale. These methods fail to capture dynamic changes in neural function and are highly influenced by subjective bias or recall variability [41-43]. Especially in evaluating treatment response, such scales do not directly reflect functional recovery within peripheral or central sensory circuits [42,43].

Consequently, an EEG–EP–based sensory nerve monitoring framework has emerged as a promising electrophysiologic approach to bridge this clinical gap. For instance, CHEPs, which are elicited by thermal stimulation through Aδ- and C-fiber activation, enable noninvasive assessment of small-fiber dysfunction or hyperexcitability [44]. Unlike subjective VAS or NRS scores, CHEPs quantitatively measure both latency (stimulus transmission time) and amplitude (response magnitude), providing an objective visualization of neural function before and after treatment.

Accordingly, by comparing EP waveforms derived from C- and Aδ-fibers before and after treatment with biologic agents (e.g., dupilumab, JAK inhibitors), it becomes possible to directly evaluate the normalization of neural responsiveness associated with therapeutic effects. This approach could form the foundation for establishing a standardized “EP-based pruritus monitoring protocol”, offering a noninvasive neurophysiologic biomarker capable of tracking real-time changes in sensory hyperexcitability in patients with chronic itch.

In most studies, CHEPs have been elicited from the forearm or calf and LEPs from the hand or face, as these regions provide stable activation of Aδ- and C-fiber pathways with minimal interference. Alternative stimulation sites, including the trunk or lower limbs, may be selected to evaluate segmental variations in sensory conduction. For longitudinal EP monitoring before, during, and after treatment, latency and amplitude should be reported as both absolute values and percent changes from baseline to facilitate reproducibility and inter-session comparison.

In essence, just as IONM protects neural integrity intraoperatively, EP technology can be extended to evaluate, monitor, and quantify sensory nerve function in chronic itch patients in real time—providing an objective clinical tool for assessing therapeutic response and functional recovery.

4. Current limitations and future directions

Several structural limitations remain in current EP research.

First, there is no clearly established disease-specific reference range for EP parameters, and demographic or technical factors—such as age, sex, stimulation site, and stimulus intensity—have not been sufficiently controlled [45,46]. For example, the latency and amplitude of CHEPs recorded from the lower limbs significantly change with increasing age, highlighting the need for standardized reference values [45,46]. Even under identical stimulation conditions, considerable inter-experimental variability exists, and the absence of a reference normalization framework has been identified as a major challenge for clinical interpretation of EP data [45,46].

Second, inconsistencies in stimulation conditions and signal-analysis parameters across studies hinder direct data comparison. Variables such as stimulus intensity, repetition rate, baseline temperature, analysis filters, and averaging (windowing) methods differ widely, resulting in significant variation in EP waveform morphology and amplitude [47-49]. Particularly, discrepancies in the habituation rate and amplitude attenuation of LEPs during repetitive stimulation have been reported among studies, raising concerns about the reliability of EPs as indices of neural plasticity. This technical heterogeneity lowers clinical reproducibility and poses a major obstacle to establishing EPs as standardized objective evaluation markers.

Third, quantitative evidence linking EP alterations to inflammatory biomarkers (e.g., IL-6, IL-31, CRP) remains insufficient. Most existing studies have focused solely on neurophysiologic changes without integrating serum inflammatory data, making it difficult to clearly delineate the inflammatory-neurophysiologic linkage [1,50,51]. Future research should therefore perform simultaneous measurement and integrated analysis of EPs and biologic markers to elucidate this relationship.

To overcome these challenges, multimodal neuroimaging approaches—integrating EEG, EP, and fMRI—are needed to analyze the spatiotemporal coupling between cortical and peripheral sensory circuits at multiple levels [52,53]. Simultaneous EEG–fMRI recordings can combine the millisecond temporal resolution of EPs with the spatial resolution of fMRI, allowing visualization of the spatiotemporal dynamics of sensory transmission from periphery to cortex [49,50]. This integrated approach provides a network-level perspective of sensory processing that cannot be captured by EP analysis alone and represents a critical direction for the future expansion of EP research.

At the clinical research level, prospective studies are required to validate EPs as objective biomarkers of therapeutic response. Standardized stimulation and analysis protocols should be applied to assess EP changes before and after pharmacologic interventions (e.g., anti-inflammatory agents or biologics), thereby determining their sensitivity and specificity [1,52]. Notably, CHEPs, which reflect sensory hyperexcitability of small-fiber pathways, have shown distinct waveform alterations in capsaicin-induced sensitization models, demonstrating strong potential as quantitative indices for tracking treatment response [52].

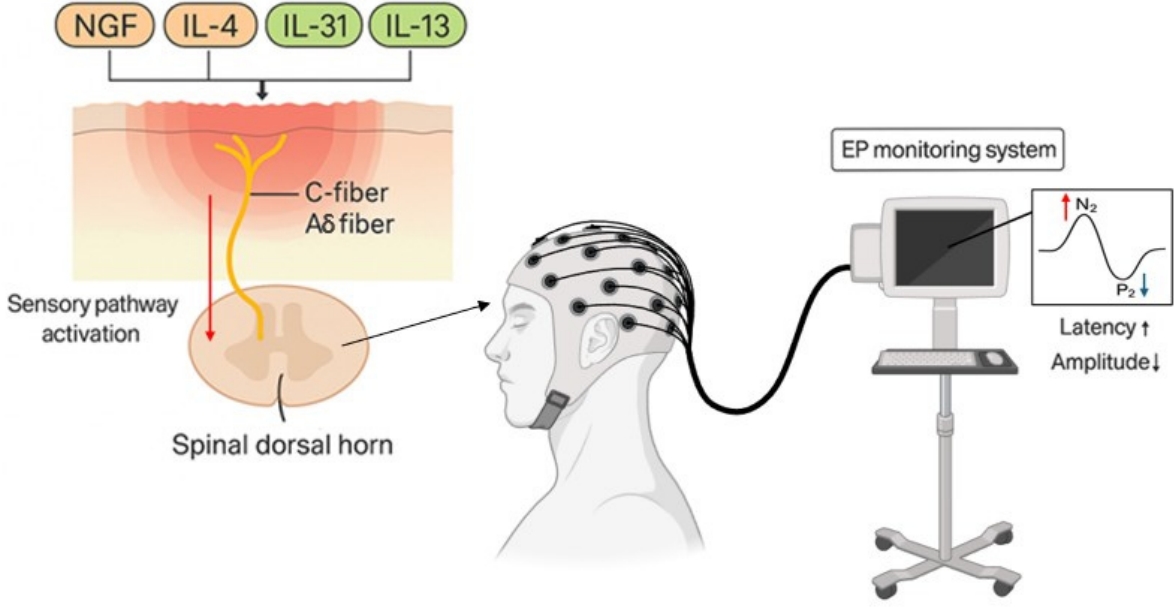

Therefore, establishing disease-specific reference ranges and defining the minimal clinically important difference through international standardization studies are essential for building reproducible EP databases. Such efforts will be key to enhancing the clinical reliability and translational applicability of EPs as objective neurophysiologic tools (Figure 1).

EP-based sensory monitoring framework for chronic itch. Inflammatory mediators such as IL-4, IL-13, IL-31, and NGF induce hyperexcitability of C- and Aδ-fibers, which transmit abnormal sensory signals to the spinal dorsal horn and higher cortical centers. This sensory pathway activation leads to altered evoked potential responses, characterized by prolonged latency and reduced amplitude of the N2–P2 complex. These electrophysiologic features can serve as objective biomarkers reflecting sensory hyperexcitability and can be applied to evaluate therapeutic responses in chronic itch. EP, evoked potential; IL, interleukin; NGF, nerve growth factor.

Conclusion

Chronic itch is not merely a sensory abnormality but a neuro-immune disorder in which inflammatory cytokines (IL-4, IL-13, IL-31), neurotrophic factors (NGF), and sensory-nerve receptors (TRPV1, TRPA1, PAR2) interact to induce sensory hyperexcitability and central sensitization at both peripheral and central levels. These pathophysiologic alterations extend beyond cutaneous inflammation, leading to reorganization of the somatosensory network in the brain. Ultimately, this process manifests as a form of persistent neural plasticity—the so-called “brain that itches” [3].

In this context, EPs have emerged as a promising noninvasive tool for visualizing electrophysiologic adaptations and neural hyperexcitability within the nervous system. Particularly, EEG-based EP analysis can simultaneously capture the temporal dynamics of sensory transmission and the amplitude of cortical responses, allowing quantitative assessment of both processing speed and activation patterns within sensory networks. This approach provides critical insight into not only peripheral fiber pathology but also functional abnormalities of the cortico-peripheral sensory circuit. Moreover, the concept of real-time neurophysiologic monitoring, already well established in IONM, can be extended to sensory hyperexcitability disorders such as chronic itch [24].

By comparing EP waveforms derived from C- and Aδ-fibers before and after treatment with biologic agents such as dupilumab or JAK inhibitors, it is possible to objectively and quantitatively evaluate the normalization of neural responsiveness. This strategy highlights the potential for developing EP-based platforms for real-time neurophysiologic monitoring of therapeutic response. Nevertheless, current EP research still faces several limitations, including the lack of disease-specific reference ranges, non-standardized stimulation and analysis protocols, and insufficient correlation with inflammatory biomarkers. To overcome these issues, multimodal neuroimaging approaches integrating EEG, EP, and fMRI are needed to enhance both temporal and spatial resolution and to elucidate the spatiotemporal coupling between cortical and peripheral sensory processing [45,46].

Future priorities include conducting prospective clinical trials to validate EPs as objective biomarkers of therapeutic response and advancing global standardization of stimulation protocols, data analysis, and signal normalization. In particular, small-fiber-dominant potentials such as CHEPs and LEPs are highly sensitive to inflammatory and sensitization states and therefore hold strong potential as quantitative clinical indices for tracking sensory hyperexcitability in chronic itch.

In summary, EPs are not merely EEG-derived waveforms but represent an electrophysiologic language through which sensory information is processed across the entire nervous system. The convergence of EEG, EP, and IONM technologies enables real-time visualization of sensory-nerve function, offering a new paradigm that integrates diagnosis, therapeutic evaluation, and neural function monitoring across chronic itch and other sensory hyperexcitability disorders.

Notes

Funding

This work was supported by the Dankook Institute of Medicine & Optics in 2025. This research was supported and funded by SNUH Lee Kun-hee Child Cancer & Rare Disease Project, Republic of Korea (grant number: 23C-023-0100), the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (RS-2023-00247651).

Conflict of Interest

Seung Hoon Woo is the Editor-in-Chief of the journal, but was not involved in the review process of this manuscript. Otherwise, there is no conflict of interest to declare.

Data Availability

None.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: HSK; Data curation: HSK; Formal analysis: HSK; Investigation: HSK; Methodology: HSK; Project administration: SHW; Software: HSK; Validation: SHW; Visualization: HSK; Writing–original draft: HSK; Writing–review & editing: all authors.