Neuromonitoring in transoral endoscopic thyroidectomy for recurrent laryngeal nerve preservation

Article information

Abstract

Transoral endoscopic thyroidectomy vestibular approach (TOETVA) is a novel scarless thyroid surgery that presents unique challenges for preserving the recurrent laryngeal nerve (RLN). Ensuring RLN integrity during TOETVA is paramount to avoid complications such as vocal cord paralysis and dysphonia. Intraoperative neuromonitoring (IONM) has emerged as an essential adjunct to optimize nerve identification and preservation in thyroid surgery. This review critically examines neuromonitoring strategies in the context of TOETVA, evaluating the use of intermittent versus continuous nerve monitoring and their integration into the transoral surgical workflow. Advances in neuromonitoring technology are also discussed, highlighting their potential to improve surgical precision and patient outcomes. Representative case studies and current evidence are synthesized to illustrate the practical benefits and limitations of IONM in TOETVA. By analyzing the existing literature and clinical practices, this review underscores the crucial role of IONM in enhancing the safety and efficacy of the transoral thyroidectomy approach while maintaining a formal, evidence-based perspective.

Introduction

Transoral endoscopic thyroidectomy vestibular approach (TOETVA) has gained traction as a scarless alternative to conventional open thyroidectomy in high-volume endocrine surgery centers [1]. To be widely adopted, TOETVA must meet the same safety benchmarks as open surgery, particularly with respect to recurrent laryngeal nerve (RLN) preservation. Injury to the RLN is one of the most significant complications of any thyroidectomy, with transient RLN paresis reported in approximately 2.6% to 5.9% of cases and permanent RLN paralysis in about 0.5% to 2.4% [2]. Such injuries can lead to vocal cord paralysis, resulting in hoarseness, swallowing difficulties, and even airway compromise in severe cases. These complications negatively impact patient quality of life and carry medico-legal implications, emphasizing the need for strategies to minimize nerve injury.

Intraoperative neuromonitoring (IONM) has become a well-established tool in open thyroid surgery for protecting the RLN. Its use provides real-time feedback on the functional integrity of nerves during surgery, which has revolutionized surgical practice by enhancing the surgeon’s ability to identify and preserve critical neural structures [3,4]. Integrating IONM into thyroidectomy protocols represents a significant advancement in improving surgical precision and patient safety [5]. By facilitating the identification and continuous functional assessment of the RLN and other relevant nerves, IONM can reduce the incidence of iatrogenic nerve injuries, thereby improving postoperative outcomes such as voice and swallowing function [6].

TOETVA introduces a different anatomical perspective and working space compared to open surgery, which can make visual identification of the RLN more challenging. The transoral approach requires meticulous technique to avoid nerve injury, heightening the value of neuromonitoring in this setting. This review provides a comprehensive overview of current neuromonitoring strategies for TOETVA, examining how intermittent and continuous monitoring modalities are applied, evaluating their efficacy in nerve preservation, and exploring emerging technologies and future directions. In doing so, we synthesize clinical evidence and case experiences to underscore the indispensable role of IONM in optimizing TOETVA procedures and ensuring they are as safe and effective as their open counterparts.

Neuromonitoring Techniques in Transoral Thyroidectomy

IONM encompasses a variety of techniques designed to assess nerve function during thyroid surgery [7]. In the context of TOETVA, the primary focus is on monitoring the RLN to prevent inadvertent injury while operating in a confined anatomical space. Two main neuromonitoring modalities are employed: intermittent intraoperative neuromonitoring (I-IONM) and continuous intraoperative neuromonitoring (C-IONM), each offering distinct advantages and limitations [8].

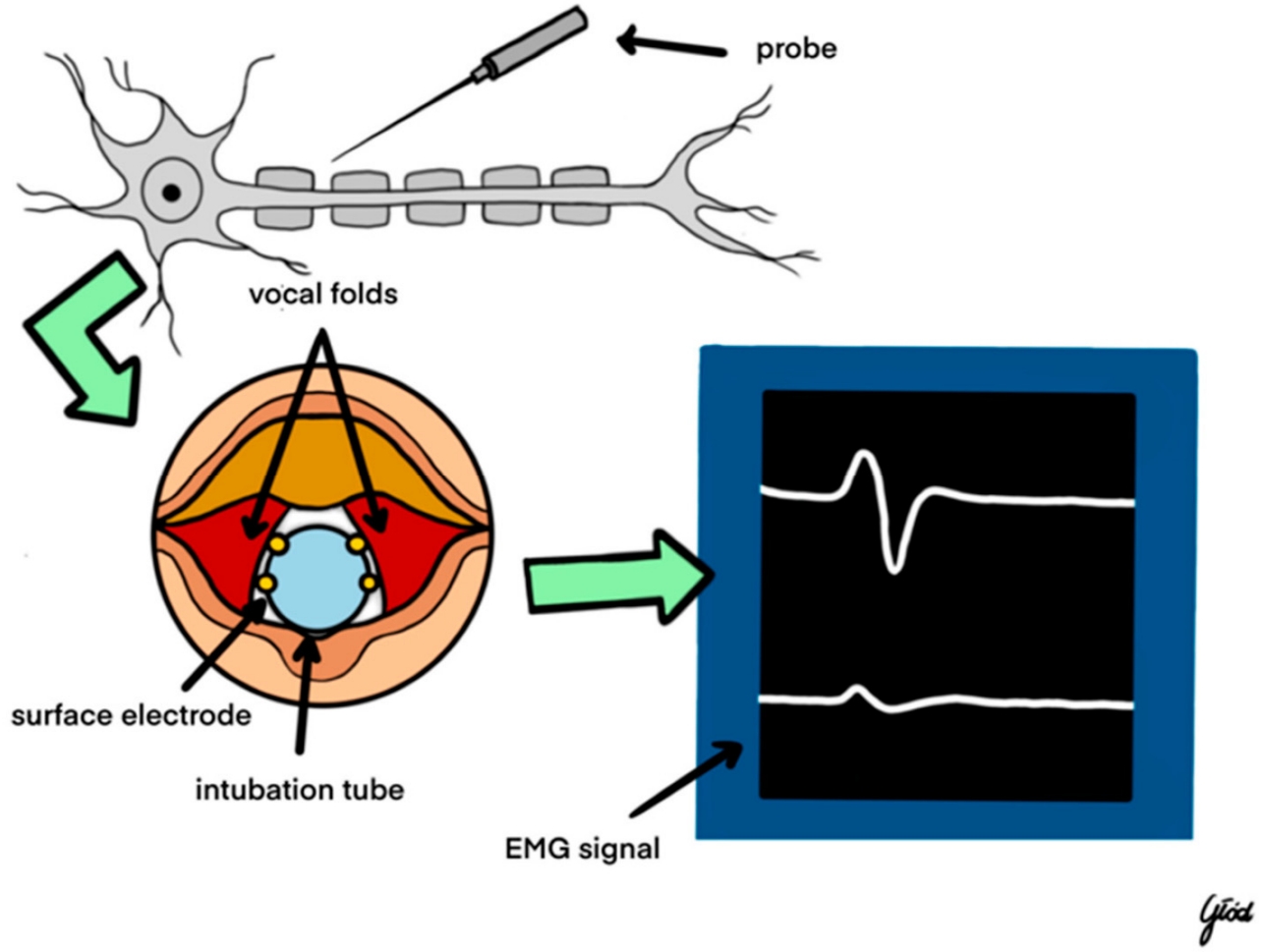

I-IONM involves periodic electrical stimulation of the RLN at specific surgical milestones, typically before and after critical steps such as thyroid lobe resection, to assess nerve integrity in those moments (Figure 1) [9]. This approach is valued for its simplicity and ease of integration into standard surgical workflows. In practice, the surgeon visually identifies the RLN (often at the ligament of Berry in TOETVA, where the nerve enters the larynx) and uses a handheld nerve stimulator probe to intermittently verify the nerve’s functionality throughout the operation [10]. This technique does not require any specialized continuous stimulation equipment; the anesthetized patient is usually intubated with an electrode-equipped endotracheal tube, and stimulation elicits an electromyographic (electromyography, EMG) response in the laryngeal muscles confirming nerve viability. However, I-IONM has limitations in detecting dynamic or transient nerve insults that may occur between stimulation points, potentially allowing some nerve stress or stretching to go unnoticed during critical maneuvers [10]. Despite this limitation, intermittent monitoring remains widely adopted due to its cost-effectiveness and straightforward implementation in thyroid surgery [11]. For example, in a recent bilateral thyroidectomy case, intermittent monitoring was used to test RLN function before and after each thyroid lobe removal, successfully confirming intact nerve function at each step and preventing any injury despite the procedure’s complexity [12].

C-IONM provides ongoing, real-time assessment of RLN function throughout the surgical procedure. This technique typically involves continuous or rapid repetitive stimulation of the vagus nerve (or RLN) and concurrent EMG recording from the laryngeal muscles, yielding a live readout of nerve activity. C-IONM setups often use a nerve electrode on the vagus nerve (which may be introduced percutaneously in TOETVA, since the vagus is not directly exposed in the transoral field) that delivers constant low-current stimuli, with any changes in the EMG signal indicating alterations in nerve function. Continuous monitoring allows immediate detection of evolving nerve stress or traction injury during the course of dissection [13]. This modality offers a more sensitive approach to nerve preservation, enabling the surgical team to respond promptly to adverse changes in nerve signals. C-IONM is particularly beneficial in complex or prolonged thyroid surgeries where the risk of nerve injury is elevated, such as large goiters or reoperative cases with scar tissue [14]. The real-time feedback provided by continuous monitoring has been shown to be instrumental in prompting immediate surgical adjustments, highlighting its critical role in enhancing surgical outcomes. For instance, the instantaneous EMG alerts from C-IONM can warn the surgeon of impending nerve strain before a loss of function occurs, allowing for timely intervention.

In TOETVA, however, continuous vagal stimulation is technically constrained, because the vagus nerve is not routinely exposed in the transoral corridor and placement of a stimulation electrode requires either a small transcervical access or a percutaneous approach. These methods may prolong operative time, crowd the narrow working space, and increase the risk of vascular or soft tissue trauma, which explains why C-IONM is still less widely implemented in TOETVA than in open surgery. Emerging techniques such as percutaneous vagal electrodes and transcartilage recording aim to provide TOETVA-compatible continuous monitoring while minimizing additional dissection.

EMG serves as the cornerstone of IONM in thyroidectomy, providing quantitative measurements of nerve function. By recording the muscle responses (typically from the vocalis or cricothyroid muscles) to nerve stimulation, EMG helps detect nerve irritation, stretching, or transection during the operation [15]. Key EMG parameters monitored include the amplitude (signal strength) and latency (signal timing) of muscle responses, which offer insight into the conduction integrity of the RLN. A significant drop in amplitude or a prolongation of latency can be early indicators of nerve compromise. Advances in EMG techniques, such as high-frequency stimulation paradigms and refined signal-processing algorithms, have improved the precision and reliability of neuromonitoring, contributing to better surgical outcomes [9,16]. These advancements help filter out background noise and reduce false-positive or false-negative readings, which is especially valuable in the busy electrical environment of an endoscopic surgery.

Beyond EMG-based methods, other neuromonitoring modalities can provide additional layers of nerve assessment. Somatosensory evoked potentials (SSEP) and motor evoked potentials (MEP) are occasionally employed in advanced cases to monitor neural pathways, though their use in thyroid surgery (and particularly in TOETVA) is far less common than EMG. The focus in thyroidectomy is predominantly on motor function preservation of the RLN, making EMG the most directly relevant modality [17]. SSEP and MEP may offer supplementary information in complex scenarios involving multiple neural structures or when the surgeon wishes to monitor additional nerves (for example, the superior laryngeal nerve or vagus nerve function) in real time [18]. However, the additional complexity and equipment required for SSEP/MEP mean they are not routinely used for standard TOETVA cases. The predominant reliance on EMG-based IONM in thyroid surgery underscores its suitability and effectiveness in addressing the specific neural preservation challenges posed by the transoral approach [19].

Efficacy of Intraoperative Neuromonitoring in Nerve Preservation

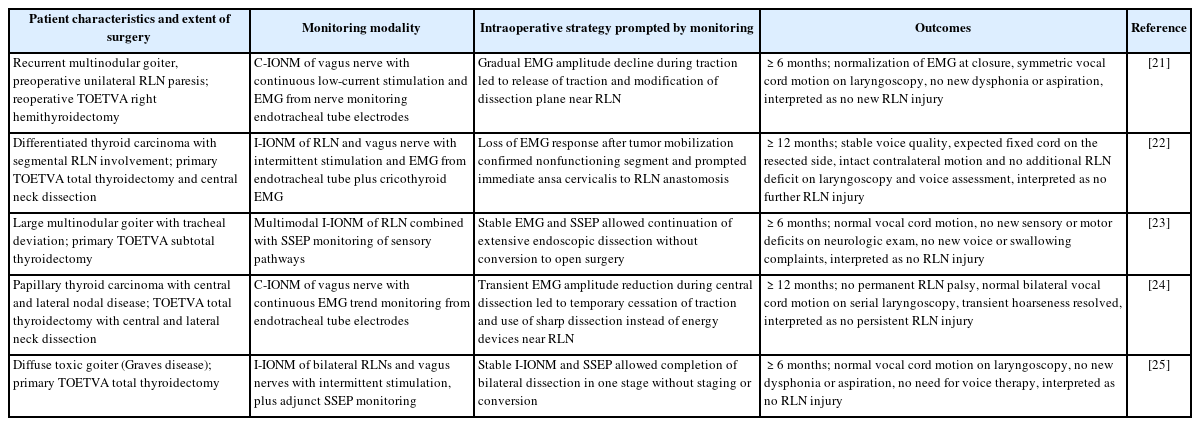

The efficacy of IONM in reducing RLN injury rates during thyroidectomy (including TOETVA) is supported by a growing body of clinical studies and meta-analyses [20-24]. Evidence from open thyroid surgeries suggests that the use of IONM is associated with a statistically significant reduction in both transient and permanent RLN palsy compared to surgeries performed without neuromonitoring. This reduction is attributed to the real-time feedback provided by IONM, which allows immediate detection and correction of maneuvers that might jeopardize nerve integrity. Although large-scale data specific to TOETVA are still maturing, initial reports indicate that neuromonitoring can enable TOETVA to be performed with RLN injury rates comparable to those of traditional open approaches, thereby upholding the principle that TOETVA’s minimally invasive nature does not come at the cost of nerve safety. Table 1 [21-25] highlights several representative case studies and clinical experiences involving IONM in TOETVA, illustrating its impact on nerve preservation and surgical outcomes in various scenarios.

Beyond statistical reductions in nerve injury rates, IONM provides qualitative enhancements to surgical technique and patient outcomes. Neuromonitoring actively enhances surgical precision by giving the surgeon continuous insight into nerve function during TOETVA. With real-time feedback, the surgeon can perform more accurate and confident dissections, knowing immediately if a maneuver is stimulating or stretching the nerve beyond safe limits. This heightened precision translates into better postoperative neural function. For example, when IONM is employed, surgeons can often preserve vocal cord mobility and avoid even transient neuropraxia that might otherwise occur without warning. Studies have noted that patients who undergo thyroidectomy with IONM assistance tend to experience fewer instances of postoperative voice changes, hoarseness, or swallowing difficulties, compared to those without IONM, contributing to higher patient satisfaction and quicker recovery [26-28]. In essence, IONM acts as a safeguard that maintains the physiologic integrity of the nerve throughout the procedure, resulting in outcomes that closely resemble the patient’s preoperative baseline function.

Continuous EMG monitoring in particular can detect subtle fluctuations in nerve activity that might not be evident to the surgeon’s eyes. This sensitivity allows for immediate intraoperative corrections. In cases where an EMG alert prompted a change in strategy (such as releasing traction on the thyroid or skeletal muscle, or dividing a threatening fibrous band), postoperative evaluations have confirmed intact vocal cord mobility—underscoring that IONM was pivotal in preventing what could have become a permanent palsy. Another important, if intangible, benefit of IONM is the increased surgeon confidence it fosters, especially in novel or high-risk situations like TOETVA. Knowing that there is continuous surveillance of RLN function can reduce the surgeon’s stress and uncertainty, which often results in a more relaxed yet attentive operative performance. Surgeons report greater assurance in their ability to identify and protect the RLN when IONM is in use, and this confidence can contribute to more consistent outcomes across different cases and even among different surgeons. Moreover, the presence of neuromonitoring encourages a team culture of nerve awareness and safety. Anesthesiologists, nurses, and surgeons become attuned to the importance of nerve preservation, for instance by avoiding deep neuromuscular blockade that could dampen EMG signals, or by carefully securing the endotracheal tube to maintain electrode contact. Altogether, these factors promote the adoption of best practices for nerve monitoring and preservation across institutions, solidifying IONM as not just a technological tool but a critical component of the surgical safety paradigm.

Outcomes and Clinical Implications

The integration of IONM into TOETVA has shown promise in improving surgical outcomes and maintaining high standards of patient safety. The primary benefit is the reduction in nerve injury rates, which, as noted earlier, is supported by data from open surgery and early transoral series. By providing real- time feedback on RLN integrity, neuromonitoring enables surgeons to avoid and immediately correct maneuvers that could lead to nerve trauma. As a result, the incidence of transient RLN palsy in experienced centers performing TOETVA with IONM appears to be low and on par with published rates in open thyroidectomy. Equally important, no permanent RLN paralysis has been reported in many TOETVA series to date, reflecting careful patient selection and the protective influence of neuromonitoring in these cases.

Beyond nerve injury statistics, patient-centered outcomes are positively influenced by the use of IONM. Patients who emerge from surgery with their RLN function intact will have normal voice and swallowing function, which translates to a smoother recovery and better quality of life. The avoidance of vocal cord paralysis means patients generally do not require additional interventions like vocal cord medialization procedures or prolonged speech therapy, thereby reducing overall healthcare utilization and cost. From a clinical implications standpoint, this reinforces that employing IONM is not merely about nerve monitoring during surgery, but about ensuring the patient’s postoperative experience is as optimal as possible.

Enhanced surgical precision is another outcome associated with routine use of neuromonitoring. Knowing the nerve’s functional status at all times encourages surgeons to be more meticulous and can even enable more aggressive yet safe dissections when removing thyroid tissue adjacent to the nerve. For instance, a surgeon might be able to remove a cancerous lymph node adherent to the RLN with greater confidence using IONM, because any sign of impending nerve dysfunction would be immediately apparent and they could adjust accordingly. This precision helps maximize the completeness of thyroid resection or nodal dissection (important for oncologic outcomes) while still preserving nerve function. Therefore, IONM has implications not only for safety but potentially for the efficacy of the thyroidectomy in disease control, by allowing thorough surgery without crossing the line into nerve damage.

The cumulative effect of these benefits positions neuromonitoring as a critical component of modern TOETVA practice. As IONM technology and techniques continue to evolve, we can expect their integration into the transoral approach to become even more refined. For example, improvements in monitoring specific to the transoral route (such as specialized transoral stimulators or better methods for continuous vagal stimulation through a minimally invasive approach) will further smooth out the process. The consistent improvement in RLN preservation outcomes and patient satisfaction with IONM has led many experts to advocate for the broader adoption of neuromonitoring as a standard of care in thyroid surgery, even more so for approaches like TOETVA where visual access to the nerve is different from the traditional open field. In summary, IONM’s positive impact on outcomes supports its routine use to ensure that TOETVA can be performed with the highest level of safety and effectiveness.

Discussion

IONM has become a valuable asset in thyroid surgery, and its role is increasingly being explored in the TOETVA. Early investigations in conventional thyroidectomy demonstrated that when IONM is used alongside meticulous surgical technique, the incidence of RLN palsy can be reduced compared to surgery without monitoring. Initial clinical experiences with TOETVA, though limited in number, have been encouraging: high-volume centers report low rates of RLN injury, suggesting that neuromonitoring helps maintain nerve safety even as surgeons adopt this new approach. However, not all studies show uniform benefit, implying that the effectiveness of IONM may depend on factors beyond the technology itself—such as the surgeon’s expertise, the complexity of the case, and adherence to proper monitoring protocols. In some series, experienced surgeons have achieved excellent outcomes with TOETVA even without IONM, whereas others have found the monitoring feedback critical, especially during their early learning curve. TOETVA also introduces specific challenges that are less prominent in open thyroidectomy, including the risk of mental nerve neuropraxia from vestibular incisions and the very narrow working corridor that tends to increase traction forces on the thyroid gland and the RLN. In this context, IONM is particularly useful because it can detect traction-related changes in EMG signal before structural nerve damage occurs and can support careful dissection strategies that respect both the RLN and the mental nerve.

The variability in reported outcomes underscores the influence of inconsistencies in neuromonitoring technique and interpretation. Without uniform standards, one surgeon’s “IONM-assisted” thyroidectomy might differ markedly from another’s. This situation highlights the importance of establishing standardized guidelines and training for the use of IONM specifically in TOETVA. Consistency in how neuromonitoring is applied—from electrode placement and stimulation settings to alert criteria and responses—will ensure that results from different practitioners are comparable and that the technique’s true value can be assessed. Comprehensive training programs can help surgeons and operating room staff become adept at using the neuromonitoring equipment and interpreting its signals correctly. With proper training, issues like inadvertent electrode displacement or misinterpretation of EMG changes can be minimized, thereby harnessing the full protective benefit of IONM. Without these measures, the potential of neuromonitoring might be undermined by operator-dependent variability and technical pitfalls, ultimately affecting patient outcomes in unpredictable ways.

Looking ahead, ongoing technological innovations are poised to further enhance neuromonitoring’s capabilities and address some current limitations. For example, research into continuous vagal nerve stimulation techniques that are more easily compatible with TOETVA (such as minimally invasive or externally applied stimulators) could simplify continuous monitoring in the transoral setting. Improved sensor designs and smarter software will likely reduce false alarms and increase reliability, even in less-than-ideal conditions. While these developments are promising, their true clinical impact will need validation through rigorous prospective studies and real-world cost–benefit analyses to determine if they justify widespread adoption in terms of improved outcomes or efficiency.

Conclusion

The application of IONM in TOETVA should be viewed as a complementary strategy that enhances surgical safety and precision, rather than as a replacement for meticulous surgical technique. When used appropriately, IONM serves as an important safeguard, especially during the learning phase of TOETVA or in anatomically challenging cases, by providing immediate functional assessment of the RLN. Surgeons are encouraged to employ neuromonitoring particularly in complex or high-risk transoral thyroidectomies, while also remaining mindful that the technology’s utility is maximized only when coupled with sound surgical judgment. Continued efforts to standardize neuromonitoring protocols and to educate surgical teams will help mitigate current limitations and variability. By harmonizing technological innovation with surgical expertise, IONM can be more effectively leveraged to improve patient safety and outcomes in TOETVA. This synergy between advanced neuromonitoring and skilled surgery paves the way for broader, evidence-based adoption of the transoral approach in thyroid surgery, ensuring that patients benefit from innovation without compromising on the standards of care for nerve preservation.

Notes

Funding

None.

Conflict of Interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Data Availability

None.

Author Contributions

All work was done by KW.