Reinnervation of a transected nerve after thyroidectomy

Article information

Abstract

Recurrent laryngeal nerve (RLN) injury remains one of the most significant morbidities of thyroidectomy. When the nerve is sacrificed either because of tumor invasion or iatrogenic injury, immediate reinnervation can restore phonatory function and prevent laryngeal muscle atrophy, even though physiological motion rarely returns. This review summarizes the current understanding of nerve degeneration and regeneration following transection of a motor nerve, the mechanisms of synkinesis, and the surgical techniques available for RLN reinnervation. Among these, the ansa cervicalis to RLN anastomosis has emerged as a practical and physiologically ideal method. Applications of nerve conduits and recent innovations in external branch of the superior laryngeal nerve reinnervation are also discussed.

Introduction

Recurrent laryngeal nerve (RLN) injury is one of the most feared complications of thyroidectomy. Despite advances in surgical techniques and routine use of intraoperative nerve monitoring, permanent RLN palsy still occurs in 0.5%–2% of operations, particularly in reoperative or malignant cases [1,2]. When the nerve is intentionally sacrificed during en bloc tumor resection or resected accidentally, the resulting denervation of the intrinsic laryngeal muscles produces glottic incompetence, breathy voice, and aspiration.

Conventional surgical options such as injection laryngoplasty, type I thyroplasty, and arytenoid adduction improve glottic closure but do not restore neuromuscular activity or prevent long-term atrophy of the thyroarytenoid and lateral cricoarytenoid muscles. In contrast, reinnervation techniques aim to restore neural tone and maintain muscle bulk. Miyauchi et al. [3] demonstrated that immediate intraoperative reinnervation, even in patients with preoperative paralysis, significantly improved postoperative voice quality and stability. Thus, when RLN resection is unavoidable, the surgeon should attempt immediate reinnervation rather than leaving the nerve transected. This article is a narrative review based on a structured search of PubMed and Scopus databases for English-language literature published between 1985 and 2024. Search terms included “recurrent laryngeal nerve,” “reinnervation,” “thyroidectomy,” and “laryngeal nerve reconstruction.” Clinical studies, review articles, and experimental works describing intraoperative nerve repair, ansa cervicalis transfer, or nerve conduit applications were reviewed. Preference was given to studies with detailed surgical methodology and measurable voice or electromyographic outcomes.

Nerve Injury and Degeneration

Following RLN resection or injury, the distal segment undergoes Wallerian degeneration within hours, characterized by axonal fragmentation, myelin disintegration, and recruitment of Schwann cells and macrophages to clear debris and support regrowth [4]. If reinnervation does not occur within months, irreversible muscle atrophy and fibrosis ensue, reducing the potential for later recovery [5]. Experimental models demonstrate that motor endplates remain viable for 6–12 months, after which functional reinnervation becomes limited [6]. Therefore, timely reconstruction during the same surgery provides the best chance for functional restoration.

Synkinesis after Reinnervation

Although reinnervation re-establishes motor input, physiologic vocal fold movement rarely returns because regenerating axons do not selectively reinnervate adductor or abductor branches. The result is synkinesis, where both muscle groups receive mixed input, producing tonic adduction without normal abduction [7]. Clinically, this yields a stable but immobile vocal fold with improved tone and closure, allowing strong phonation but potentially limited respiration. Crumley’s model of “favorable synkinesis” explains that successful reinnervation enhances voice even when movement is absent, as the adductor tone dominates functionally [7].

Surgical Techniques of Reinnervation

1. Overview and principles

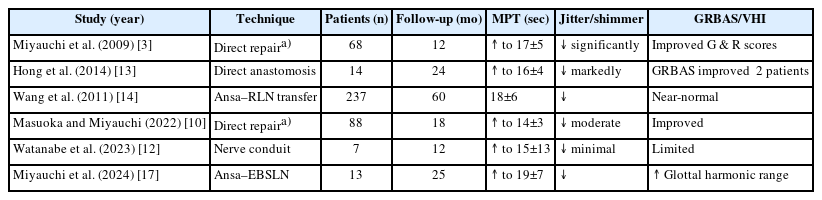

When the RLN is sacrificed during thyroidectomy, immediate reinnervation is the most physiologic means of preserving phonatory function. The primary aim is to re-establish motor input to the intrinsic laryngeal muscles to maintain muscle tone and prevent atrophy, even though true vocal fold movement rarely returns [3,4]. Reinnervation achieves dynamic neural tone rather than static medialization and can be performed with minimal added operative time in the thyroidectomy field. Fundamental principles include tension-free coaptation, meticulous handling of nerve ends, and alignment of fascicles under microsurgical magnification. The distal RLN stump should be identified and preserved whenever possible. Immediate intraoperative reconstruction produces better outcomes than delayed repair, as prolonged denervation leads to end-plate degeneration and fibrosis [3]. Papadopoulou et al. [8] reviewed 18 clinical studies and concluded that early repair consistently improves voice quality, regardless of technique. Representative clinical studies comparing reinnervation outcomes by technique are summaried in Table 1.

2. Direct end-to-end neurorrhaphy

Direct neurorrhaphy is preferred when both nerve ends are available and can be approximated without tension—typically when the transection is sharp and the segmental loss is less than 5 mm. Under microscopic visualization, the cut ends are freshened to healthy fascicles. The epineurium is coapted with two or three 9-0 nylon sutures using an interrupted pattern. A small amount of fibrin glue can supplement the repair to ensure fascicular contact and prevent suture-induced trauma. Gentle mobilization of the larynx and thyroid remnant can relieve minor tension at the coaptation site [3,4].

Miyauchi et al. [3] demonstrated that immediate direct repair during thyroidectomy leads to significant improvement in phonation, even in patients who already had preoperative paralysis. Postoperative electromyography (EMG) showed reappearance of motor unit potential within 6 months. When feasible, direct repair is considered the standard method for recent transection with preserved nerve ends.

3. Interposition (cable) nerve grafting

If a segment of the RLN must be resected with tumor and the gap exceeds 5–10 mm, direct repair may cause traction, and an interposition graft is required. Suitable donors include the great auricular nerve, ansa cervicalis branch, or sural nerve [9,10]. After measuring the defect with the neck in a neutral position, a graft of slightly greater length is harvested to prevent tension. The graft is reversed to minimize misdirected branching, then coapted to the proximal and distal RLN stumps using 9-0 or 10-0 nylon sutures under microscopy. Each junction may be reinforced with fibrin sealant. Biological wraps (fascia or absorbable sheath) can be applied to prevent scar tethering [11,12].

When the proximal RLN is partially damaged but still conductive on intraoperative neuromonitoring, neurorrhaphy between viable fascicles and the graft can yield functional reinnervation. Early reconstruction—ideally during the same operation—allows regenerating axons to reach the target muscle before irreversible atrophy develops [4]. Cable grafting restores muscle tone and bulk in the majority of patients. Studies comparing direct repair and interposition grafting report equivalent improvements in maximum phonation time, shimmer, and perceptual voice quality [8]. Synkinetic reinnervation prevents muscle wasting, resulting in a stronger, steadier voice. However, delayed grafting beyond 6–12 months has inferior outcomes due to muscle fibrosis [13].

4. Ansa cervicalis to recurrent laryngeal nerve reinnervation

When the proximal RLN cannot be preserved—such as when invaded to its origin or sacrificed during central compartment dissection—the ansa cervicalis provides an ideal motor donor. It is purely motor, of comparable diameter to the RLN, and easily accessible in the thyroidectomy field [14]. The physiologic advantage lies in the ansa’s tonic firing pattern, which provides continuous low-level stimulation of the reinnervated laryngeal muscles. This maintains adduction and prevents atrophy while avoiding paradoxical synkinesis [7].

The main ansa trunk or a dominant branch is identified and used for end-to-end anastomosis. Postoperative EMG typically demonstrates reinnervation potentials within 3–6 months [15].

The ansa–RLN technique has shown reproducible, long-term success. In a large series of 237 patients, Wang et al. [14] found that postoperative stroboscopy and acoustic measures were indistinguishable from those of normal controls. Similar results have been reported in other cohorts [15]. The donor site morbidity is negligible, and the procedure adds only 10–15 minutes to operative time. Because the reinnervated fold remains in a slightly adducted, tensioned position, the patient retains a strong, non-breathy voice while the contralateral fold handles abduction. This “physiologic medialization” makes the ansa–RLN method particularly suited for unilateral resection [15]. In practice, anatomical variations such as duplication of the ansa loop or dominance of the superior root should be recognized intraoperatively. When multiple donor branches are available, the branch with the largest diameter and closest proximity to the RLN stump is preferred to minimize tension and optimize axonal alignment [14,15].

5. Vagus-to-recurrent laryngeal nerve anastomosis

Vagus transfer is rarely indicated today but remains a salvage option when both the proximal RLN and ansa cervicalis are unavailable. Voice improvement is variable, and donor morbidity—including dysphagia, weak cough, and loss of vagal reflexes—limits its use [7,10].

Application of Nerve Conduits

Synthetic and biological nerve conduits can bridge short RLN gaps when direct repair is not feasible. Clinical studies have demonstrated that collagen conduits can support axonal regeneration and maintain alignment over short defects [12,16]. However, outcomes depend heavily on immediate surgery and distal muscle viability. However, current evidence is limited to small case series, and long-term outcomes remain uncertain. Future developments in bioactive or electrically conductive scaffolds may enhance targeted axonal regeneration and functional specificity [12,16]. Comparative analyses indicate that immediate (within 24 hours) reinnervation yields superior electromyographic recovery and perceptual voice quality compared to delayed procedures performed months later. Nonetheless, even delayed reinnervation can improve muscle tone and voice stability relative to static medialization alone [8,13].

Reinnervation of the External Branch of the Superior Laryngeal Nerve

Injury to the external branch of the superior laryngeal nerve (EBSLN) reduces pitch range and vocal endurance. Miyauchi et al. [17] introduced ansa cervicalis to EBSLN anastomosis, restoring high-tone phonation in most patients without donor-site complications. Reported postoperative improvements include recovery of G3–H5 pitch range and sustained high-frequency phonation, supporting its role in professional voice users [17].

Conclusion

When the recurrent or superior laryngeal nerve is transected during thyroidectomy, leaving it unrepaired should no longer be standard practice. Immediate reconstruction—by direct anastomosis, cable graft, or especially ansa cervicalis transfer—preserves muscle tone, prevents fibrosis, and yields strong, stable phonation. Physiological movement does not return, but functional voice nearly always does.

Notes

Funding

None.

Conflict of Interest

Hyoung Shin Lee is an editorial board member of the journal, but was not involved in the review process of this manuscript. Otherwise, there is no conflict of interest to declare.

Data Availability

None.

Author Contributions

All work was done by HSL.