Introduction

The hospitalization rate for degenerative myelopathy is estimated at 4.04 per 100,000 people per year, which is associated with high rates of surgical intervention [

1]. On the other hand, the incidence of thoracic degenerative myelopathy is 0.9 per 10,000 [

2]. As a critical step in surgical intervention, Plata Bello et al. [

3] advocated routine neuromonitoring during the preoperative positioning of patients with cervical degenerative myelopathy. They found that transcranial motor evoked potentials (TC-MEPs) were particularly useful in these cases [

3]. However, loss of the signal may be a false alarm. Furthermore, it is not possible to obtain a baseline TC-MEP in all cases. Myelopathy, thoracic surgery, and diabetes are particularly associated with failure to obtain TC-MEPs [

4].

The most common associations with eventful IOM in a retrospective study of 100 patients with cervical myelopathy were cervical ossified posterior longitudinal ligament, long-standing or high-grade myelopathy, and negative K-line [

5].

However, the use of intraoperative neruomonitoring (IOM) in decompression surgery for cevical and thoracic myelopathy poses a legal and ethical dilemma. If the patient’s positioning causes loss of IOM signals, and every attempt has been made to restore them, including repositioning, can the surgery continue? While it is tempting to cancel the surgery to avoid any harm in these cases, what if the patient awakens with neurological deterioration? Positioning the patient is technically a surgical step, and abandoning the surgery without decompression does not completely absolve the surgeon of blame. The patient has given his consent to have his spinal cord decompressed to halt the neurological deterioration of a known condition, and awakening with further deterioration and residual compression can be extremely disappointing. It could mean a lost opportunity for recovery, when some recovery could have occurred had the surgery been performed as agreed upon. On the other hand, continuing the surgery in a position that is presumed to cause mechanical damage to the spinal cord could cause harm and therefore be considered inappropriate.

We elected to ask spinal experts, mainly from the UK, for their take on the best practice in these situations.

Methods

We sent out a survey questionnaire through the British Association of Spine Surgeons (BASS) website exclusive to consultant spine surgeons. The survey was sent via BASS Newsletter to members on 22nd January 2025. It was open for voting for one month. Because it was intended only for consultants, not all BASS members were expected to participate. Therefore, the total number of people who were eligible to vote cannot be precisely determined. The survey was assessed and approved by the United Kingdom Spine Societies Board before the form was sent out. We also approached some surgeons directly. The survey had the following two questions:

1. You have positioned a patient for decompression surgery for myelopathy and subsequently completely lost IOM signals. Would you abandon surgery?

2. How do you justify your choice?

The first question had “yes” or “no” options and the second optional question had a free text entry.

We then conducted a systematic review of the medical literature to find the best available evidence on this topic.

Results

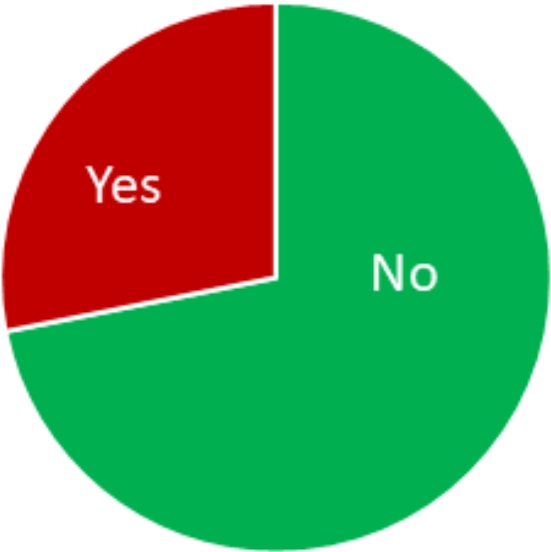

We received 32 responses. About 72% recommended continuing surgery (95% confidence interval, 55%–85%), while the remainder chose to discontinue it. Five surgeons stated that they do not routinely use IOM in degenerative myelopathy surgery. Two of them would only use IOM in patients with good neurological status. The ethical and legal imperative to avoid harm was the reason given by two surgeons for cancelling surgery. On the other hand, five surgeons justified their continuation by the need to decompress the already known compromised spinal cord. The most common response was to emphasize the need to discuss this scenario with the patient preoperatively during the consent process (six responses). One surgeon emphasized the need to assess the impact of neck movement on neurological symptoms preoperatively (

Table 1,

Figure 1).

Discussion

The rate of complications in spinal surgery is 1% on average, but higher in complex surgeries [

4]. IOM is a safety tool that is more commonly used in spine theatres for live feedback between neural tissues and surgeons. Establishing baseline TC-MEPs and somatosensory evoked potentials readings is important before and after positioning the patients, although recording them is not always possible. Any subsequent drop in signals should prompt a reassessment of the surgical plan. Routine checks of the connections of IOM wire connections along with the patient’s vital signs are the usual initial responses to any decrease in IOM signals.

In degenerative cervical myelopathy, the prone position may place pressure on the cord if neck flexion or, more commonly, extension further constricts the already critically narrow spinal canal. X-ray and optimisation of neck position should be performed promptly. Also, general haemodynamic responses to prone position may impair the circulation to the cord and exacerbate its ischemia.

IOM is not a universally adopted practice in the thousands of decompressive operations for myelopathy performed worldwide annually. A total of 19% of our sample confirmed that they would not routinely use it, and would only monitor the myelopathic patients with favourable neurology. In fact, a survey conducted by BASS and Society of British Neurological Surgeons found that the use of neuro-monitoring in cervical and posterior thoracic decompression for myelopathy is “neither mandatory nor commonplace”. It is highly recommended for anterior thoracic discectomy, but not mandatory. The BASS website recommends considering a return to the supine position in response to a decreased or lost IOM. The decision to proceed with surgery is considered individual and should be based on the patient’s underlying condition [

6].

Two important legal points were made in the responses to our survey regarding the reaction to dropped IOM signals after positioning. Firstly, “Those who proceeded without monitoring at all may be subject to the patient suing who can say: Had I but known monitoring was available, I would not have proceeded without the monitoring” stated one respondent. Secondly, “if you use monitoring, you cannot then ignore it. This patient had potentials when positioned which were subsequently lost. There is a medicolegal and ethical responsibility to stop the procedure. If the argument is that you cannot stop the procedure then why are you monitoring? If the patient has no potentials when positioned you can decide about proceeding on a risk vs benefit assessment.”, as another consultant reported.

Head positioning is critical in cervical myelopathy surgeries. Readjusting the position recovered signals in four out of five patients who had eventful IOM among 75 patients in one study. The fifth patient in that study had postoperative neurological deterioration but surgical decompression was completed [

3]. Reversing the positioning to neutral supine could be logic but does not necessarily mean recovery or safety.

What if the loss of signals is not reversed by abandoning the surgery? A patient who agreed to undergo surgery and then woke up with a new deficit without his stenosis being resolved would be nothing but extremely frustrated. “The loss of IOM signals suggests that there is a critical degree of cord compression and this is best treated surgically at the earliest opportunity. Abandoning surgery would just be 'kicking the can down the road'. In my opinion it is best to inform patients”, as per one opinion in the survey.

Both approaches may have their justifications, but not discussing the possibility of early signal loss with the patient in advance may be indefensible. One aspect of the concept of informed consent is that the patient must be informed of all treatment options, including the option of not intervening [

7]. Complications from surgical intervention may be grounds for malpractice claims, but so too may failure to intervene in a timely manner to prevent the natural progression of the disease process—for example, worsening of degenerative cervical myelopathy—be considered negligent [

8]. Therefore, it is prudent to discuss with the patient whether to use IOM and, if so, what reasons might lead him to forego surgery, especially before putting “knife to skin”.

Conclusion

IOM is an adjunct that is not universally used in decompressive surgery for myelopathy. Early loss of signals after the patient is positioned is a relative contraindication to proceeding with surgery. Nonetheless, there is no consensus among spinal surgeons regarding the necessity of continuing surgery. One important consideration is to include this scenario in the consent process and decide with the patient on the course of actions in case of loss of IOM signals.

This survey has limitations. It was only distributed to consultants working in the UK. The number of responses was small and there could have been selection bias in the responders. However, it shows a wide range of reasons behind each arm and should help guide surgeon’s choice when faced with the question of the survey in the real life.

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Download Citation

Download Citation Print

Print