Preventing recurrent laryngeal nerve injury in thyroidectomy: the role of continuous vagal monitoring

Article information

Abstract

Recurrent laryngeal nerve (RLN) injury remain the most serious complication of thyroidectomy, particularly in high-risk cases involving reoperations, malignancy, or complex anatomy. Continuous intraoperative neuromonitoring (C-IONM) offers real-time nerve stimulation and electromographic feedback, enabling early detection of nerve stress and prevention of irreversible damage. This systematic review evaluates the efficacy, predictive accuracy, and clinical impact of C-IONM in reducing RLN injury during high-risk thyroid surgery. While bread population studies show limited benefit over visual identification or intermittent monitoring, targeted analyses reveal that C-IONM significantly lowers the incidence of permanent RLN injury in complex procedures. Its high negative predictive value supports safe surgical staging to prevent bilateral vocal cord palsy, transforming intraoperative strategy and elevating standards of care. Despite technical challenges and modest setup time, C-IONM demonstrates a favorable safety profile and cost-effectiveness when applied to high-risk cohorts. Adherence to standardized protocols from the International Neural Monitoring Study Group is essential for optimal outcomes. C-IONM should be considered a necessary adjunct in high-risk thyroidectomy, with future randomized trials needed to further quantify its impact.

Introduction

Thyroidectomy is a common surgical procedure, yet it carries the inherent risk of injury to the recurrent laryngeal nerve (RLN), which can result in transient or permanent vocal cord palsy (VCP) [1]. RLN injury remains the most critical complication of this surgery, leading to significant patient morbidity including voice dysfunction, compromised airway protection, and potential aspiration risk [2]. While the overall incidence of RLN injury in general patient population is reported to be relatively low—for instance around 1.1% in one retrospective cohort [2]—the potential for permanent bilateral RLN palsy presents a catastrophic outcome, often necessitating a permanent tracheostomy for airway management [3,4]. Reducing this incidence, particular in complex cases, is a fundamental goal for modern endocrine surgery.

This systematic review assesses the use of Continuous Vagal Nerve Monitoring (continuous intraoperative neuromonitoring, C-IONM) to reduce temporary and permanent RLN injury rates during high-risk thyroid surgery (e.g., re-operation or cancer). We conducted selective search in the biomedical literature database of PubMed which covered 2015–2025. The methodology strictly includes only high-quality randomized controlled trials and prospective studies and other systematic reviews that covered the following keywords: laryngeal nerve injuries, thyroidectomy, intraoperative neuromonitoring.

The initial efforts to safeguard the RLN utilized visualization alone (VA) combined with meticulous dissection. This was later augmented by intermittent intraoperative neuromonitoring (I-IONM), which involved periodic stimulation of the RLN or vagus nerve to confirm identification and structural integrity at specific points during the dissection [5,6]. However, I-IONM is fundamentally limited; it serves as an identification tool and can only detect a nerve injury after it has occurred [7-9]. C-IONM represents a major technological advancement achieved through the placement of a specialized electrode clamp on the vagus nerve proximal to the surgical field. This technique allows for the repetitive, ongoing stimulation of the vagus nerve, generating real-time electromyographic (EMG) signal from the laryngeal muscles. This dynamic monitoring capability is crucial, as it allows the detection of nerve distress or impending injury before irreversible damage is inflicted, thereby enabling immediate intervention [5,10].

The utility and cost-effectiveness of C-IONM are most pronounced when deployed in populations where the baseline risk of RLN injury is significantly elevated. High-risk thyroidectomy procedures are characterized by factors that obscure anatomical visualization increase the duration of nerve exposure, or involve significant neural manipulation [2,11]. Specific factors associated with a significantly increased risk of operative RLN injury include prior thyroid surgery (re-operation for recurrent goiter), thyroid carcinoma, extensive lymph node invation, and the technical requirement of a total thyroidectomy [11]. One retrospective study specifically identified prior thyroid surgery as a significant risk factor (p=0.006), alongside advanced age (over 45 years) and male ender [1]. Furthermore, complex anatomical variants, such as the non-recurrent laryngeal nerve (NRLN), drastically increase the difficulty of identification and protection, thus qualifying the procedure as high-risk [11,12].

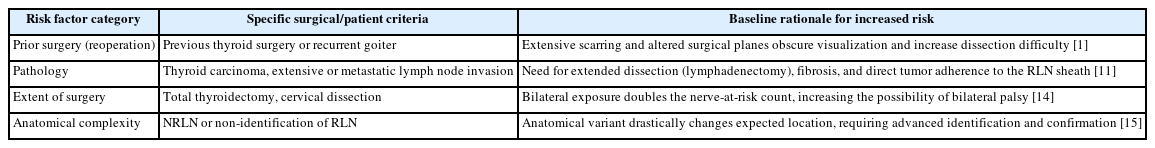

The concentration of these risk factors within specific patient groups establishes an elevated baseline neurological complication rate. Since published analyses suggest the IONM becomes cost-effective when the complication rate exceeds a threshold of 0.3% [13], the application of C-IONM to preoperatively defined high-risk cohorts is transitioning from an optional adjunct to a necessary standard of care. This approach ensures that the sophisticated protective technology is deployed where the medical benefit in terms of complication prevention, and the economic benefit, in terms of averted long-term care costs, are maximized. Table 1 [1,11,14,15] lists down defined high-risk factors for RLN injury based on surgical and patient specific criteria.

Comparative Efficacy of Continuous Intraoperative Neuromonitoring

Initial systematic reviews comparing intraoperative neuromonitoring (whether Intermittent or Continuous) against VA during thyroidectomy provided conflicting or inconclusive evidence regarding widespread risk reduction [16,17]. A 2022 meta-analysis on eight randomized clinical trials showed no statistically significant difference in the reduction of total, transient, or permanent RLN injury when using IONM compared to VA [18]. Similarly, pooled data comparing I-IONM and C-IONM outcomes in some analyses suggested largely overlapping 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) for injury rates, with a pooled definitive injury rate of 0.395% for I-IONM and 0.4% for C-IONM [19]. These findings often lead to the conclusion that the anatomical visualization remains the gold standard and that the IONM should not replace meticulous surgical technique [20].

A more granular analysis focusing specifically in high-risk surgical scenarios, such as thyroid reoperation, reveals a clear benefit associated with IONM use. The failure to demonstrate a universal reduction in transient RLN injury in general populations [19,20] suggest that C-IONM may no effectively prevent minor, reversible neural irritations. However, its effectiveness lies in preventing the progression to severe, irreversible damage. In a focused meta-analysis, the use of IONM in thyroid reoperation demonstrated a statistically significant reduction in permanent RLN injury compared to the VA group [20]. The summary odds ratio for permanent RLN injury was 0.62 (95% CI, 0.4–0.9; p=0.03), indicating a material protective effect. The specific incidence of permanent RLN injury in the IONM reoperation group was 2.39% compared to 2.88% in the VA group [20]. This statistically significant difference, although seemingly small in absolute terms is clinically profound, as permanent RLN palsy results in lifelong morbidity and requires subsequent corrective procedures [2]. This observation confirms that C-IONM provides a unique protective capacity, acting as an electrophysiological fail-safe that intervenes against the specific high-impact events that cause permanent damage.

Beyond general reoperations cases, C-IONM proves useful in addressing anatomical variations and complexity. A study evaluating C-IONM in patient with a NRLN found the technique to be feasible and safe, providing helpful diagnostic information to prevent VCP [21]. Specifically, in NRLN, a shorter vagus nerve onset latency 93.0 msec) was observed, which may serve as a characteristic indicator for distinguishing this anatomical variant intraoperatively [21]. In high-volume centers utilizing C-IONM, the technique not only reduces RLN injury but also allows for the assessment of functional prognosis, thereby enabling the timely initiation of rehabilitative treatments [22]. These findings collectively support the conclusion that C-IONM significantly reduces the risk of injury, particularly unilateral injuries, when optimized through continuous monitoring and standard techniques [23].

Electrophysiological Principles and Predictive Value

The predictive power of C-IONM hinges on the continuous measurement of two key electrophysiological parameters: nerve amplitude and latency [5]. The process begins with establishing the baseline signal, or V1, immediately after the vagus nerve has been exposed and secured with the monitoring electrode [24]. This V1 value serves as the normative reference point for subsequent signal changes, the final assessment involves recording the V2 signal upon completion of the dissection of the RLN and before closing the incision. The integrity of this V2 signal is highly predictive of postoperative vocal cord function [14].

The unique advantage of C-IONM is its ability to detect nerve distress by surgical maneuvers—most commonly traction—before that distress results in permanent structural damage [5]. The system alerts the surgeon to an impending injury when a severe combined effect is registered: a reduction of the EMG signal amplitude greater than 15% coupled with an increase in latency greater than 10%, sustained over 40–60 seconds [25]. The drop in amplitude reflects a condition block or axonal injury, while increased latency is often indicative of traction or demyelination [15]. Importantly, these signal changes reliably signal impending nerve injury, enabling immediate corrective action. Studies have shown that when adverse EMG changes are noted, prompt modification of the causative surgical maneuver leads to recovery of the EMG signal and aversion of impending RLN palsy in approximately 70% of patients [25].

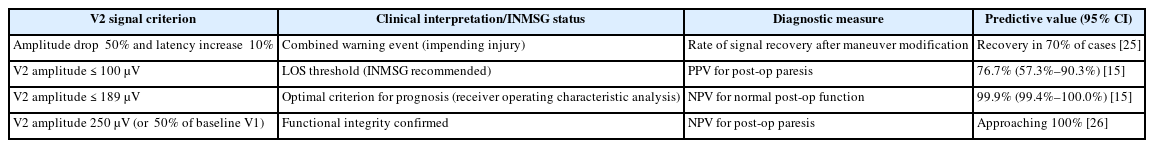

To standardize clinical practice and interpretation, the International Neural Monitoring Study Group (INMSG) has established quantitative criteria for defining significant signal degradation. The INMSG defines loss of signal (LOS) as the loss of recognizable EMG signal characterized by a curve amplitude falling below the 100 μV threshold [15,26].

Analysis of the predictive accuracy of the final V2 signal relative to postoperative vocal fold paresis suggest that while the INMSG threshold (≤100 μV) is highly effective, the most optimal criterion identified via Receiver Operating Characteristic curve analysis is a V2 amplitude ≤189 μV [26]. Successful implementation relies heavily on adherence to the INMSG guidelines, which provide the methodology for proper equipment setup and algorithms for interpreting changes in amplitude and latency [27].

The Clinical utility of C-IONM is best summarized by its predictive values. The technique exhibits an extremely high negative predictive value (NPV), which is the probability of normal postoperative function when the intraoperative signal is intact. When a robust V2 signal is obtained (e.g., amplitude>250 μV or >50% of the initial V1 value), the NPV for normal postoperative cord function approaches 100% [15,23]. For the optimal criterion of V2 amplitude ≤189 μV, the NPV was 99.9% [26].

Conversely, the positive predictive value (PPV) indicates the likelihood of postoperative paresis when a LOS occurs. For the INMSG-recommended criterion (V2 amplitude≤100 μV), the PPV is substantial, approximately 76% [26]. Although a LOS is highly predictive of injury, the fact that the PPV is not 100% emphasizes the possibility of signal recovery (partial or complete) at the end of the operation, which must be assessed before drawing the final prognosis [28].

The Robust Statistical predictability of C-IONM, particularly its high NPV, is critically dependent upon strict adherence to standardized technical protocols established by the INMSG [27]. Conflicting outcomes often seen in heterogeneous literature can be directly attributed to variations in anesthetic technique, tube positioning, and inconsistent application of neuromuscular blocking agents, all of which compromise signal integrity and increase the risk of false alerts [28]. The standardization mandated by C-IONM therefore elevates the rigor of the entire surgical team’s practice. Table 2 [15,25,26] enumerates quantified criteria for classification of signals based on INMSG standards used for prognoses.

Impact on Intraoperative Strategy and Bilateral Palsy Prevention

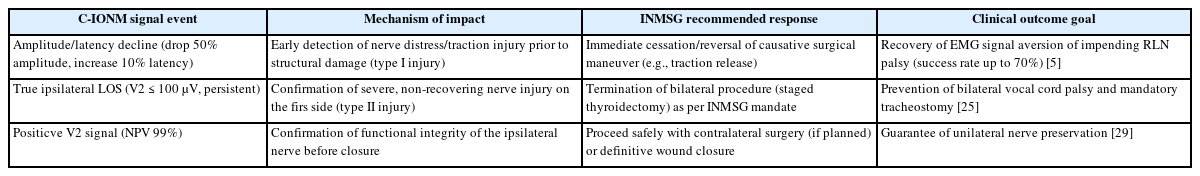

The clinical value of C-IONM is fundamentally realized through its ability to directly influence surgical strategy in real-time. By providing dynamic feedback, the monitor allows the surgeon to link the signal degradation—often manifesting as drop in amplitude—directly to a specific maneuver, such as excessive traction or the use of an energy device near the nerve [7]. This immediate feedback mechanism allows for the detection of potentially reversible type I injuries [22]. When severe signal blocks occur, the surgeon is immediately warned and can cease or reverse the causative action, such as releasing traction on the thyroid lobe [28]. This capacity for modification led to surgical plan changes in 31.3% of cases exhibiting severe signal blocks in one cohort, successfully averting permanent damage in a large proportion of cases [5,22].

When a LOS is detected during the dissection of the RLN, the surgeon must follow a systematic troubleshooting algorithm to determine if the event is a true neurological injury or a technical failure (false LOS) [28]. Technical errors, which can be caused by monitoring equipment dysfunction, endotracheal tube malposition, or residual neuromuscular blockade, must be excluded first [24]. A critical diagnostic step is the stimulation of vagus nerve on the contralateral side. If the contralateral vagus nerve stimulation yields a positive EMG signal, it confirms that the monitoring equipment is functional, thereby classifying the ipsilateral signal loss as a true LOS event requiring immediate clinical action [28]. The most crucial strategic impact of C-IONM is its function as a safety mechanism for preventing the catastrophic outcome of bilateral VCP. If a true ipsilateral LOS persists without recovery at the end of the first side’s operation, the nerve is deemed severely injured [28]. In this scenario, the INMSG consensus mandates that the planned bilateral procedure must be terminated and staged, meaning the surgeon stops the procedure and delays the contralateral dissection until the nerve has sufficient time to recover postoperatively [3].

This staging strategy is vital because bilateral VCP can lead to acute laryngeal obstruction, often requiring tracheostomy in approximately 30% of affected patients [2]. C-IONM elevates the standard of care for planned bilateral procedures, especially in high-risk patients. Because the monitoring system provides a rapid high-certainty prognosis for unilateral nerve function (NPV 99% when V2 is robust), it empowers the surgeon to proceed safely or to halt the operation based on the definitive electrophysiological evidence, thus making bilateral palsy an almost entirely preventable disaster in monitored cases [3,28]. Table 3 [5,25,29] summarizes impact of implementing C-IONM based on focused surgical outcome. This transforms the use of C-IONM from a technical preference into a component of ethical surgical practice for bilateral thyroidectomy.

Technical Implementation, Safety Profile and Economic Considerations

The implementation of C-IONM requires specific technical expertise and adds some complexity to the operative sequence. The time required to establish monitoring, including vagal nerve dissection and electrode placement, has been reported to range from 3 to 26 minutes, with a median setup of 6 minutes. This constitute a relatively small percentage of the total surgical procedure time (ranging from 2.9%–12.2%) [30]. Despite its advantages, C-IONM is not devoid of technical limitations [5]. Challenges often involve system malfunctions or setup error. Electrode displacement particularly stimulation clamp on the vagus nerve, is a recognized complication, reported to occur 11 times in 5 cases in one prospective trial, frequently necessitating replacement [30]. The occurrence of technical error necessitates meticulous troubleshooting to distinguish a genuine neurological event (true LOS) from an equipment or setup failure (false LOS).

C-IONM is broadly regarded as a safe adjunct in thyroid surgery, particularly when compared to the morbidity associated with VCP [27] notwithstanding its use is associated with rare specific complications related to electrode placement and vagal nerve stimulation. Adverse events reported include a case of temporary vagal nerve paralysis secondary to dislodged electrode. Likewise, in the initial phase of surgery shortly after calibration, there has been one reported case of hemodynamic instability manifested as bradycardia and hypotension [31]. Apprehensions surrounding the need to access the vagus nerve by opening the carotid sheath, coupled with the possibility of stimulation-related complications, have contributed to skepticism regarding the widespread adoption of C-IONM. Nonetheless, the overall rate of the procedure-related complications remains very low in large cohort studies, validating its favorable safety profile.

The upfront cost associated with the routine use of C-IONM equipment increase the immediate surgery cost. Yet, a comprehensive economic evaluation requires balancing this expense against the potential for long-term cost savings derived from preventing complications. Analysis suggests that IONM is highly cost-effective when the baseline neurological complication rate of the surgical procedure exceeds 0.3% and the rate of prevention following IONM alert is greater than 14.2%. For high-risk procedures—such as reoperations or cases involving malignancy—the RLN injury rates significantly exceeds the 0.3% threshold [1,30]. Preventing a single permanent VCP, which otherwise necessitates subsequent costly interventions such as voice therapy injection laryngoplasty, or arytenoid adduction [11,16], can result in substantial long-term economic savings and enhanced patient quality of life. Therefore, C-IONM is an economically justified investment in high-risk scenarios [14].

The effectiveness and safety data support the growing international acceptance of C-IONM as a useful technique for mitigating risk of RLN and external branch of the superior laryngeal nerve injury [27]. The widespread utility of the technology hinges entirely on the standardized application. The INMSG has established comprehensive guidelines detailing recommended methods for equipment setup, troubleshooting algorithms for signal errors, and interpretation of electrophysiological data. It is imperative that the surgeons intending to use IONM are fully familiar with these INMSG protocols, as they provide the framework necessary for translating electrophysiological signals into actionable surgical decisions [27].

The mandatory technical requirements for successful C-IONM—including standardized anesthesia, precise endotracheal tube placement, and strict adherence to signal interpretation algorithms—drive a higher standard of technical rigor across the operating room team [21,26,27]. The successful implementation of C-IONM protocols within high-volume center this acts as a quality assurance mechanism, standardizing surgical practice and training the next generation of surgeons in data-driven neural protection techniques.

Conclusion and Future Directions

C-IONM has become a vital tool in high-risk thyroid surgery, offering real-time functional nerve monitoring beyond simple identification. While broad studies show mixed results, targeted meta-analyses confirm C-IONM significantly reduces permanent transient laryngeal nerve injury in complex cases like reoperations. Its key advantage is early detection of nerve stress, enabling timely surgical adjustments and preventing irreversible damage. High negative predictive value ensures functional integrity, supporting staged thyroidectomy when persistent ipsilateral LOS occurs to avoid bilateral VCP. Given its proven efficacy, predictive strength (INMSG criteria), and cost-effectiveness in high-risk settings, C-IONM should be the standard for patients undergoing reoperations, malignancy-related dissections, or total thyroidectomy. Despite strong observational support, future randomized trials focused on high-risk groups and standardized protocols are essential to quantify C-IONM’s precise impact.

Notes

Funding

None.

Conflict of Interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Data Availability

None.

Author Contributions

All work was done by PA.