Illuminating minds vs. chemical control: a comprehensive comparison of optogenetics and chemogenetics in neuromodulation

Article information

Abstract

Neuromodulation has significantly advanced with optogenetics and chemogenetics, providing precision in manipulating neural pathways for research and therapy. This review compares these methods by evaluating their molecular mechanisms, spatio-temporal control, applications, limitations, and future directions. Optogenetics employs light-sensitive ion channels for rapid neuronal control, ideal for fast neural processes. Chemogenetics utilizes synthetic ligands activating engineered receptors, enabling prolonged, non-invasive modulation suited for chronic studies. While optogenetics offers superior temporal precision, its invasiveness contrasts with chemogenetics’ non-invasive yet slower kinetics. Technical challenges include stability, phototoxicity, and ligand pharmacokinetics. Emerging hybrid systems, improved gene delivery techniques like clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats, and next-generation tools promise enhanced specificity and safety. Both methods demonstrate therapeutic potential in neurological and psychiatric conditions, although ethical and safety concerns regarding viral vectors and off-target effects remain critical. Combined, these tools significantly advance neuroscience and neuromodulatory treatments.

Introduction

Neuromodulation is a critical process in the nervous system that involves the dynamic regulation of neuronal activity and signaling pathways to influence various functions, including mood, cognition, and behavior. This regulation can be achieved through various mechanisms, ranging from the release of neurotransmitters and hormones to the application of electrical impulses. The significance of neuromodulation in neuroscience is underscored by its potential therapeutic applications in a range of neurological and psychiatric disorders, emphasizing the need for precise control over neural circuits for both research and clinical purposes [1].

Over the last few decades, innovative techniques such as optogenetics and chemogenetics have emerged, revolutionizing the field of neuromodulation. Optogenetics involves the use of light-sensitive proteins, known as opsins, that are genetically introduced into specific types of neurons. By delivering light of specific wavelengths, researchers can achieve precise control over neuronal activity, enabling the modulation of complex neural circuits with high spatial and temporal resolution [2-4]. This methodology has been particularly advantageous in studying neuronal networks and understanding their contribution to behavior and disease [5,6].

On the other hand, chemogenetics involves the use of engineered receptors sensitive to specific chemical ligands. One prominent approach is the designer receptors exclusively activated by designer drugs (DREADDs), which allow researchers to modulate neuronal activity via the administration of synthetic [7,8]. Unlike optogenetics, which require continuous light delivery, chemogenetic techniques allow for prolonged modulation of neuronal activity following a single administration of a ligand, thereby offering advantages in studying chronic conditions where long-term alterations in neuronal behavior are required [9,10].

Both optogenetics and chemogenetics have gained traction for their applicability in preclinical and clinical research, particularly in exploring treatment avenues for neurological disorders such as epilepsy, Parkinson’s disease, and depression [11,12]. Recent studies have highlighted the strengths of optogenetics in providing real-time feedback on neural circuit dynamics, allowing researchers to establish causal relationships between neuronal activity and behavioral [13-15]. However, chemogenetics offers the practicality of extended modulation without the need for direct light application, which can be logistically challenging in vivo [16].

The comparative merits of these techniques underscore a broader trend in neuroscience towards the integration of optogenetic and chemogenetic methods. Such hybrid approaches can enhance the precision of neuromodulation while providing flexibility in experimental design, addressing the specific demands of various research questions [17]. As the field continues to evolve, numerous studies have begun to explore synergistic applications of these techniques to refine our understanding of complex neural behaviors and their underlying mechanisms [12,18].

Historical and Conceptual Background

1. Origins and evolution of optogenetics

Optogenetics is a groundbreaking technique that began in the early 2000s, when scientists discovered that proteins from light-sensitive microorganisms, especially algae, could be used to control nerve cells. These proteins, such as channelrhodopsins, act as switches that open in response to specific light wavelengths. When inserted into neurons using genetic engineering, they allow researchers to turn these cells on or off using light. Early experiments showed that channelrhodopsins could trigger neuronal firing with remarkable precision [19-21].

Soon after, additional tools were developed, like halorhodopsins, which silence neurons when activated by yellow light. The combination of excitatory and inhibitory proteins allowed scientists to finely tune brain activity. Optogenetics quickly became a powerful method for understanding how specific groups of neurons contribute to perception, emotion, movement, and cognition. Over time, it has been applied to more complex models, including primates and even human tissue, demonstrating its broad potential in both basic research and clinical investigations [22,23].

2. Development and advantages of chemogenetics

Around the same time, researchers developed chemogenetics, a method that uses engineered receptors activated by special synthetic drugs (e.g., DREADDs). Unlike optogenetics, chemogenetics doesn’t need light to work. Instead, it offers longer-lasting control over neurons using non-invasive drug delivery. This makes it useful for studying long-term brain processes or treating chronic conditions [24,25].

3. From animal research to human applications

Both techniques started in animal studies but are now being tested in humans. Optogenetics is especially helpful in fast-paced experiments where timing is crucial, while chemogenetics is better for slower, long-lasting effects. Today, researchers often combine the two approaches to take advantage of each method’s strengths. These tools are changing how we study the brain and opening new possibilities for treating diseases like Parkinson’s, depression, and epilepsy [26,27].

Mechanisms of Neuronal Activation and Inhibition

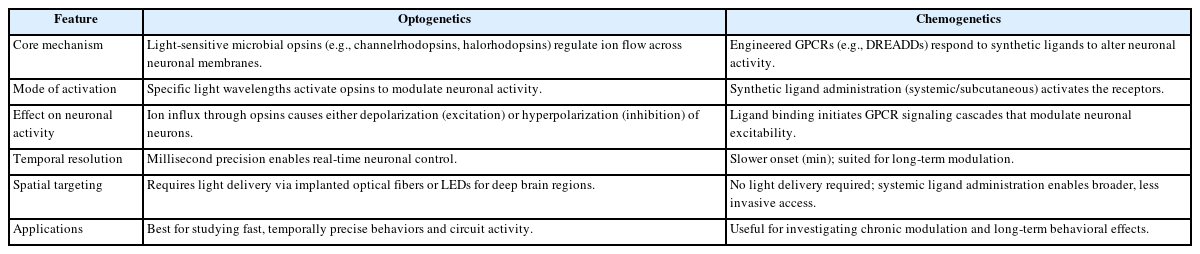

Recent advances in neuromodulation, especially in optogenetics and chemogenetics, have given scientists powerful tools to study how brain cells are turned on or off (Table 1). These tools help us understand how brain circuits work and are also being explored for new treatments in brain-related diseases [28-30].

Optogenetics uses light-sensitive proteins to control neurons. When light hits these proteins (like channelrhodopsins), it opens channels in the cell’s surface, letting in positive ions like sodium. This causes the neuron to become active and send signals. This process happens very quickly, allowing precise control of brain activity in real-time [31-34]. For stopping activity, other proteins (like halorhodopsins) open up channels for negative ions like chloride. This makes neurons less likely to fire. These tools allow researchers to turn brain activity on or off and study its effects on behavior, such as during anxiety or seizures [35,36].

Chemogenetics employs DREADDs that modulate neurons through intracellular signaling cascades [10]. G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) activate phospholipase C, increasing intracellular calcium and promoting excitation, while inhibiting cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) production, enhancing potassium conductance and reducing excitability. These signaling pathways influence synaptic strength and plasticity, aiding studies on learning, memory, and neuropsychiatric conditions. Importantly, both methods can modulate glial cell activity, with astrocytes playing key roles in neuromodulatory responses via gliotransmission. Optogenetics and chemogenetics, provide unprecedented opportunities to examine the intricate mechanisms of neuronal activation and inhibition. Understanding the mechanisms involved in these technologies not only serves to define their respective operational frameworks but also elucidates their broader implications for neuroscience research and therapeutic applications [37-39].

Genetic and Molecular Tools

Optogenetics and chemogenetics are advanced techniques that allow researchers to manipulate brain cell activity with great precision. Each method uses specific genetic tools that are delivered into the brain using viral vectors and targeted to selected neurons through genetic strategies. This section focuses on the technical aspects of these constructs, how they are delivered, and how researchers ensure their expression in the desired cell types.

In optogenetics, the main constructs are microbial opsins that vary in their ion selectivity, activation wavelength, and expression efficiency. These differences allow researchers to tailor their experiments to achieve precise control depending on whether they need fast excitation or inhibition of neurons. Newer versions of opsins continue to improve on light sensitivity, targeting precision, and minimal cellular stress. In chemogenetics, engineered GPCRs, primarily DREADDs, are used [40,41]. These tools are customized for different types of cellular responses, such as calcium signaling or cAMP suppression. Their long-lasting effects and compatibility with systemic drug delivery make them ideal for studying prolonged behaviors and chronic brain states.

For both approaches, the genetic constructs are typically introduced into the brain using viral vectors [13]. Among these, adeno-associated viruses (AAVs) are preferred due to their safety profile, ability to infect neurons, and stable gene expression over time. Lentiviruses are also used in cases where genome integration is desired for long-term studies. These viral vectors can be injected directly into targeted brain areas to achieve localized expression, and newer methods such as ultrasound-mediated delivery offer less invasive alternatives for broader applications.

Accurate targeting of specific cell types is crucial for both techniques. In optogenetics, cell-type specificity is often achieved using recombinase systems like Cre-loxP or Flp-FRT, which allow opsins to be expressed only in selected neurons based on the genetic background of the animal model [42]. Chemogenetics uses similar targeting methods, combining specific promoters with viral vectors or transgenic models to restrict DREADD expression to the desired neuron populations. Intersectional strategies, where two or more genetic elements must be present for expression are also increasingly used for even finer control.

In summary, optogenetics enables rapid, reversible control of neural activity using light, while chemogenetics offers prolonged, drug-based modulation of brain circuits. Both rely on genetically engineered constructs, carefully selected delivery systems, and precise genetic targeting. These technologies continue to evolve, improving their reliability, safety, and compatibility with complex experimental designs and therapeutic goals.

Temporal and Spatial Control

Optogenetics and chemogenetics offer distinct advantages when it comes to controlling the brain over time and space. Optogenetics provides extremely rapid control, on the scale of milliseconds, making it ideal for studying fast brain activities like decision- making or reflexes. In contrast, chemogenetics operates on a slower timescale, with effects that begin minutes after drug administration but can last for hours. This makes chemogenetics more suitable for exploring longer-term behaviors or brain states, such as mood or sleep regulation [43,44].

Spatially, optogenetics is limited by the reach of light, which typically affects only the area surrounding the implanted fiber. Although new technologies like holographic stimulation can broaden coverage, the need for surgical light delivery remains a limitation. Chemogenetics, using systemically administered drugs, can modulate larger brain regions non-invasively. However, this broader effect may reduce precision by unintentionally affecting nearby or unrelated neurons [45-47].

Both methods allow for cell-type-specific targeting through genetic tools, such as Cre-loxP systems in transgenic animals. These tools help ensure that only certain neurons are affected, even when large brain regions are exposed to light or drugs. However, practical limitations such as light penetration in optogenetics or drug spread in chemogenetics can still influence the actual specificity achieved in experiments.

When considering duration and reversibility, optogenetics enables immediate control that stops as soon as the light is turned off, which is valuable for precise timing. However, its effects are brief unless light is continuously delivered. Chemogenetics, while slower to activate, provides long-lasting effects with a single dose, which is better for studying sustained changes in behavior or brain function [48,49]. Overall, the choice between these techniques depends on the experimental goals, whether real-time precision or long-term modulation is required.

Experimental and Clinical Applications

Optogenetics has become a powerful tool in neuroscience research, allowing scientists to control specific neurons with high temporal precision. This has enabled detailed studies of how neural circuits influence behaviors like learning, memory, decision-making, and sensory processing [50,51]. By activating or silencing certain neurons during tasks, researchers can directly observe the causal role of brain activity in behavior. Chemogenetics complements this by offering slower but longer-lasting control, making it better suited for studying changes that unfold over minutes to hours. Using DREADDs, scientists can explore how specific neurons contribute to sustained behaviors or long-term brain plasticity [52,53].

Both techniques have shown great potential in animal models of neurological and psychiatric disorders. Optogenetics has been used to interrupt seizures in epilepsy models and to normalize behavior in models of depression and anxiety. Chemogenetics, in turn, has demonstrated promise for conditions like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease [54]. Targeting key brain areas can improve motor function or cognitive symptoms. It also allows studying and potentially regulating neural circuits involved in mood and stress-related disorders.

The possibility of translating these technologies into human therapies is actively being explored. In the field of vision restoration, optogenetics has progressed to early clinical trials where light-sensitive proteins are expressed in retinal cells to help patients regain visual perception [55]. It’s also being studied in cardiology, where light control of heart tissue may help treat arrhythmias [56]. These developments show that optogenetics has potential far beyond brain research, though it still requires invasive light delivery systems, which may limit its clinical use.

Chemogenetics is also moving toward clinical application, particularly for treating chronic pain, depression, and other mood disorders. Its ability to modulate brain activity through non-invasive drug delivery makes it an attractive alternative to conventional medications, potentially with fewer side effects [57-59]. While both optogenetics and chemogenetics are promising for therapeutic use, challenges such as safe gene delivery, precise targeting, and long-term safety still need to be addressed before these technologies can become widely used in clinical settings.

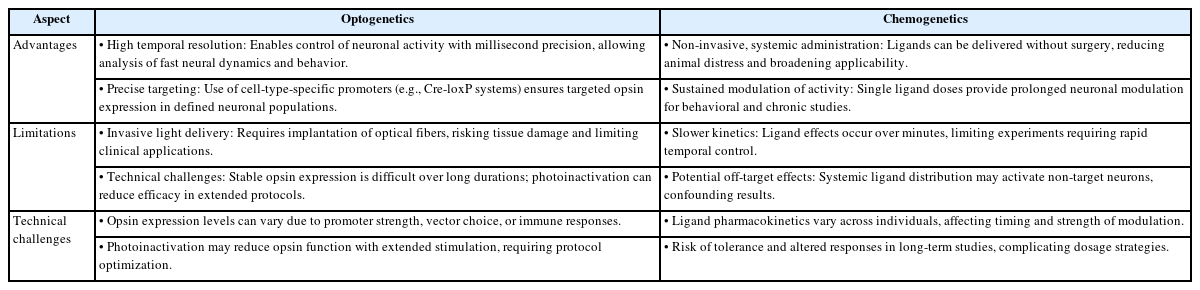

Table 2 summarizes the key advantages and limitations of optogenetics and chemogenetics as neuromodulatory tools. It highlights their distinct mechanisms, technical considerations, and suitability for different experimental paradigms. Understanding these differences is critical for selecting the appropriate method based on research objectives, required temporal precision, and potential constraints related to invasiveness, specificity, and long-term applicability [60-66].

Ethical and Safety Considerations

As optogenetics and chemogenetics move closer to clinical use, several ethical and safety issues must be addressed. One major concern is the use of viral vectors to deliver genes into the brain. While AAVs and lentiviruses are effective tools for gene transfer, they can trigger immune responses, causing inflammation or tissue damage [67-69]. Repeated exposure may worsen these reactions, especially in long-term treatments. There’s also the risk that viral DNA might unintentionally integrate into important parts of the genome, potentially disrupting normal cellular function or even contributing to tumor development [70,71].

Another concern is the possibility of off-target effects and toxicity. Sometimes, the genetic tools (opsins or DREADDs) might be expressed in unintended cell types, leading to unexpected outcomes. In chemogenetics, the synthetic drugs used to activate receptors could affect non-target neurons, resulting in unwanted changes in behavior [72]. In addition, some viral vectors can cause local inflammation or damage to sensitive brain cells, and these effects may vary depending on the method used or the individual’s age and immune system. These risks are especially important to consider for vulnerable populations, such as children.

To reduce these risks, researchers are exploring alternatives to viral delivery. Non-viral methods, such as nanoparticles, liposomes, and biodegradable carriers, are being developed to safely and efficiently introduce genes into target cells without triggering immune reactions [73-75]. These approaches may offer better safety profiles, especially for repeated use or sensitive applications. Ongoing innovation in biomaterials and delivery systems aims to improve both safety and effectiveness, while also addressing ethical concerns around the invasiveness and permanence of gene-based brain interventions.

Finally, as these technologies move toward human use, it’s essential to ensure proper ethical oversight. Clinical trials must clearly explain potential risks and long-term consequences to participants, using transparent and thorough consent processes. Regulatory frameworks should require both rigorous testing before approval and ongoing safety monitoring after treatment begins. Collaboration among scientists, ethicists, healthcare providers, and policymakers is key to guiding the responsible use of optogenetics and chemogenetics in a way that protects patients and supports innovation.

Future Directions and Innovations

The next generation of neuromodulation focuses on hybrid opto-chemogenetic platforms, which combine acute light-based control with prolonged ligand-based modulation. These systems enable multiplexed manipulation across time scales and cell types. Clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)-based genome editing improves gene targeting precision and allows single-cell resolution in modifying neuronal properties [76-80].

Advances in gene delivery include biodegradable scaffolds, magnetic nanoparticles, and blood-brain barrier-penetrant carriers. New opsins and DREADD variants are being engineered for enhanced sensitivity, reversibility, and spectral diversity. Meanwhile, base and prime editors reduce genomic instability and support safe, heritable modifications. Collectively, these innovations promise to extend neuromodulatory techniques into personalized neurotherapies.

Conclusion

Optogenetics and chemogenetics have revolutionized how we manipulate and understand neural circuits. Each offers distinct strengths—optogenetics in temporal precision and chemogenetics in long-term, non-invasive modulation. Hybrid approaches and CRISPR-based gene targeting are ushering in a new era of neuromodulation with greater specificity, scalability, and clinical relevance. Addressing ethical and technical challenges remains vital for translating these tools into safe and effective therapies. As these technologies mature, they hold promise not only for understanding brain function but also for treating an expanding spectrum of neurological and psychiatric conditions.

Notes

Funding

None.

Conflict of Interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Data Availability

None.

Author Contributions

All work was done by NTC.