| J Neuromonit Neurophysiol > Volume 5(2); 2025 > Article |

|

Abstract

Mitochondrial dysfunction is a significant contributor to neurodegeneration, impacting neuronal health and function across various neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases. This review explores therapeutic strategies focused on mitochondrial rejuvenation, encompassing small molecule and metabolic modulation, mitochondrial augmentation therapies, and neuromodulatory approaches. Promising interventions include nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide boosters, antioxidants, and mitochondrial biogenesis activators that enhance energy metabolism and reduce oxidative stress. Stem cell-mediated mitochondrial transfer, isolated mitochondrial transplantation, and extracellular vesicle-based delivery represent innovative augmentation therapies aimed at restoring mitochondrial function. Additionally, red and near-infrared photobiomodulation alongside electrical and chemical neuromodulation is examined for its potential to enhance mitochondrial efficacy safely. The review also discusses translational barriers, including delivery challenges, timing of interventions, compatibility in donor-host integration, and the need for standardized functional assessments. Finally, clinical prospects highlight the importance of combining mitochondrial therapies with regenerative strategies and using engineering approaches for targeted and durable restoration of mitochondrial function, paving the way for enhanced outcomes in aging and neurodegenerative diseases.

Mitochondria, the essential organelles within cells, are primarily known as the powerhouse, generating adenosine triphosphate (ATP) through oxidative phosphorylation. However, their role extends far beyond energy production; mitochondria are implicated in several pivotal functions including calcium homeostasis, regulation of apoptotic processes, and production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), all of which are crucial for maintaining cellular health and functionality in neurons [1,2]. Neurons are particularly dependent on mitochondrial function due to their high energy demands; optimal mitochondrial activity is vital for neurotransmitter release and synaptic plasticity, both of which underpin neurotypical function [3]. Disturbances in mitochondrial dynamics, such as fission and fusion, can lead to impaired energetic status, which is detrimental for neuronal health, particularly in environments laden with energy demands [4].

As research advances, mitochondrial dysfunction emerges as a precursor to neurodegenerative processes, manifesting early in conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Parkinson’s disease (PD), and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) [5,6]. Accumulating evidence suggests that mitochondrial impairments not only contribute to cellular energetic deficits but also amplify oxidative stress and inflammatory responses within neural pathways, thereby accelerating neurodegeneration [7,8]. For instance, dysfunctional mitochondria may lead to increased ROS production, resulting in oxidative damage to proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids, thereby impairing neuronal viability and signaling [9]. Furthermore, studies indicate that mitochondrial abnormalities can evoke significant metabolic dysregulation, underlining their role as a common denominator across various neurodegenerative conditions [10].

The hypothesized link between mitochondrial dysfunction and aging provides further insight into its relevance in neurodegeneration. As age advances, mitochondrial function naturally declines, characterized by reduced mitochondrial biogenesis, increased mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) mutations and deletions, and diminished bioenergetic capacity [11,12]. This decline in mitochondrial integrity is compounded by age-related accumulations of oxidative damage, which serve to compromise neuroprotection and exacerbate neurodegenerative processes [13]. In essence, the deterioration of mitochondrial function may contribute to a vicious cycle, where aging-associated deficits in mitochondrial dynamics and performance facilitate neurodegeneration [14,15].

Recognizing the importance of mitochondrial health in the prevention and therapy of neurodegenerative disorders lays the groundwork for potential therapeutic strategies focused on mitochondrial repair and rejuvenation. Targeting mitochondrial dysfunction holds promise for ameliorating neuronal damage and enhancing synaptic repair. Recent advances suggest that interventions aimed at stimulating mitochondrial biogenesis, enhancing mitochondrial antioxidant defenses, or promoting mitophagy, wherein the selective removal of damaged mitochondria could be pivotal in restoring neuronal health and function [4,16]. For instance, agents such as resveratrol and compounds targeting the sirtuin pathway have demonstrated efficacy in mitigating oxidative stress and enhancing mitochondrial function [17]. Moreover, the restoration of mitochondrial function through gene therapy or pharmacological means has shown promise in preclinical models, acting as a pivotal strategy in neuronal rejuvenation [18].

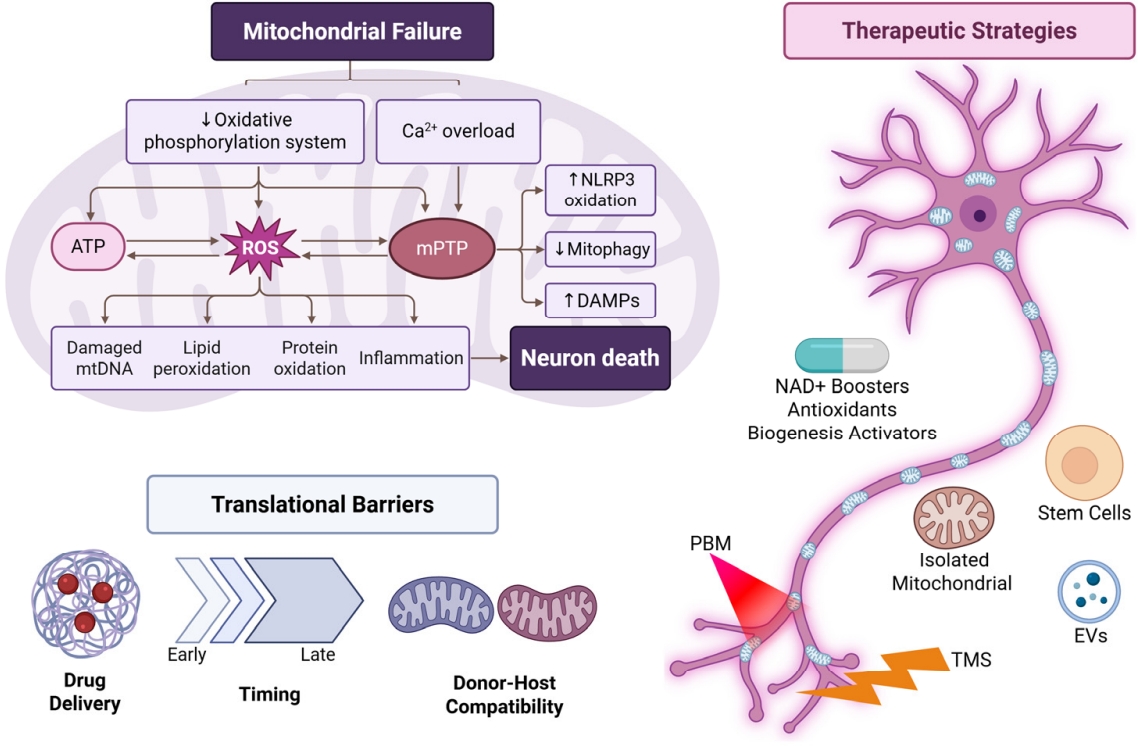

This review aims to synthesize current understanding of how mitochondrial dysfunction drives neuronal impairment and to evaluate therapeutic strategies designed to restore mitochondrial health in the context of neural aging and disease. By highlighting mechanistic targets, emerging interventions, and translational considerations, the goal is to define a clear pathway toward clinically meaningful neuronal rejuvenation through mitochondrial repair. Figure 1 illustrates how mitochondrial dysfunction contributes to neuronal degeneration and summarizes the therapeutic approaches discussed in this review.

Mitochondria are essential organelles within neurons, responsible for ATP generation through oxidative phosphorylation and the regulation of various metabolic pathways critical for neuronal health and function. Mitochondrial dysfunction represents a significant pathophysiological event in neurodegenerative diseases, contributing to neuronal cell degeneration. This section elaborates on the mechanisms that underlie mitochondrial failure in neurons, focusing on reduced oxidative phosphorylation leading to ATP deficits, calcium imbalance and excitotoxicity, mtDNA mutations, impaired proteostasis and mitophagy, and disruptions in axonal mitochondrial transport.

One fundamental role of mitochondria is ATP production via oxidative phosphorylation, a process critically dependent on the integrity of the electron transport chain (ETC) [19]. When oxidative phosphorylation becomes compromised, decreased ATP production occurs, which is particularly detrimental to neurons due to their high energy demands. For instance, in AD, there is a marked decline in oxidative phosphorylation efficiency, leading to energy deficits that contribute to synaptic dysfunction and neuronal death [20]. Mitochondrial dysfunction can manifest as various mitochondrial abnormalities, such as loss of mitochondrial membrane potential, reduced activity of key ETC complexes (like complex IV), and elevated production of ROS, which further exacerbate mitochondrial damage and impair ATP synthesis [21].

Studies have shown that an increase in oxidative stress can inhibit the mitochondrial ETC, leading to bioenergetic failure in neurons. For example, oxidative modifications to proteins within the ETC can hinder their function, creating a vicious cycle where energy deficiency perpetuates further mitochondrial dysfunction [22]. This deficient ATP production impacts neurons’ ability to maintain membrane potential and perform essential physiological functions, ultimately resulting in neuronal dysfunction and activation of apoptotic pathways [23].

Mitochondria are crucial for calcium homeostasis, which is fundamental for neuronal signaling and excitability. Calcium imbalance occurs due to disrupted mitochondrial calcium uptake and buffering capacity, often leading to excitotoxicity, a pathological process characterized by excessive stimulation of neurons by excitatory neurotransmitters like glutamate [24]. The regulation of intracellular calcium by mitochondria is vital as it affects neurotransmitter release and synaptic plasticity. Damaged mitochondria can result in elevated cytosolic calcium levels, overwhelming buffering capacity and triggering excessive neuronal activation. This process leads to neuronal injury through activation of calcium-dependent apoptotic pathways [24,25].

Moreover, oxidative stress can exacerbate calcium dysregulation by promoting the opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore, which facilitates the unnecessary release of calcium into the cytoplasm and promotes the release of pro-apoptotic factors such as cytochrome c. The importance of calcium homeostasis underscores that mitochondrial failure entails not only energy deficits but also disruptions in key signaling mechanisms leading to neuronal excitotoxicity, culminating in neurodegeneration.

mtDNA is particularly susceptible to mutations due to its proximity to the ETC, where ROS are generated as byproducts. The accumulation of mtDNA mutations contributes to mitochondrial dysfunction, implicated in various neurodegenerative diseases [26]. Impaired mtDNA repair mechanisms can exacerbate this issue, compromising mitochondrial function, altering proteostasis, and reducing mitochondrial biogenesis [27].

The failure of mitophagy, the selective removal of damaged mitochondria, is critical in compounding mitochondrial dysfunction in neurons. Proteins like PINK1 and Parkin play pivotal roles in recognizing and targeting dysfunctional mitochondria for degradation [28]. Impairments in these pathways can lead to the accumulation of damaged mitochondria, further contributing to oxidative stress and calcium dysregulation, ultimately resulting in neuronal death. Research indicates that neurons exhibit slower mitophagy rates compared to other cell types, making them particularly vulnerable to mitochondrial dysfunction over time [29,30]. Thus, the interplay between mtDNA mutations, proteostasis, and ineffective mitophagy exemplifies a multifaceted mechanism through which mitochondrial integrity is compromised, promoting neurodegenerative processes.

Mitochondrial transport along axons is crucial for maintaining energy homeostasis and meeting the local energy demands of synapses. Disruption in mitochondrial transport can lead to an inadequate supply of ATP to distal neuronal compartments, contributing to synaptic dysfunction. Mutations affecting proteins necessary for mitochondrial transport, such as dynein and kinesin, can impede mitochondrial movement, leading to energy deficits in neurotransmission areas [25].

Starvation or pathological conditions can exacerbate mitochondrial transport issues, resulting in stationary mitochondria that fail to support synaptic function and ultimately leading to neuron death. In rodent models of AD, impairments in axonal transport were linked to reduced mitochondrial motility along axonal microtubules, demonstrating how such disruptions can affect synaptic plasticity and overall neuronal function [31]. The interplay between mitochondrial transport and neuronal health underscores the critical need for effective mitochondrial dynamics to maintain neuronal integrity and function.

The persistence of proper mitochondrial function is crucial for neuronal health, given the central role of mitochondria in energy production, metabolic regulation, and calcium homeostasis in neurons. Mitochondrial dysfunction is a hallmark of many neurodegenerative diseases, underscoring the need for effective therapeutic strategies aimed at rejuvenating these organelles. This review discusses several promising therapeutic avenues: small molecule and metabolic modulation, mitochondrial augmentation therapies, and neuromodulatory and photonic approaches (Table 1).

The first approach to mitochondrial rejuvenation involves the use of small molecules that target mitochondrial pathways. Four main strategies have emerged: nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) boosters, antioxidants, sirtuin activators, and mitochondrial biogenesis activators.

NAD+ is a critical coenzyme involved in redox reactions and energy metabolism. As organisms age, NAD+ levels decline, contributing to mitochondrial dysfunction [32]. Administration of NAD+ boosters, such as nicotinamide riboside and nicotinamide mononucleotide, has been shown to enhance mitochondrial function, promote ATP production, and improve neuronal health in models of age-related cognitive decline [33]. These compounds can augment oxidative phosphorylation efficiency and enhance mitochondrial repair mechanisms, making them compelling candidates for therapeutic strategies targeting neurodegenerative disorders.

Oxidative stress is a significant contributor to mitochondrial dysfunction. Antioxidants, such as N-acetylcysteine (NAC), have been utilized to mitigate oxidative damage to mitochondrial components, thereby improving function and cellular viability. Studies in mouse models of spinal muscular atrophy have demonstrated that NAC supplementation can restore mitochondrial transport and morphology by reducing the generation of ROS and rescuing motor neuron degeneration [34]. The application of antioxidants in clinical settings for neurodegenerative diseases holds great promise, particularly in combining them with other pharmacological interventions.

Sirtuins are a family of NAD+-dependent deacetylases that play significant roles in mitochondrial function, DNA repair, and cellular stress response [35]. Activation of sirtuins, particularly SIRT1, has been linked to enhanced mitochondrial biogenesis and improved mitochondrial function. Compounds like resveratrol have been shown to activate sirtuins, thereby enhancing their protective effects against mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress. This adds a layer of complexity to therapeutic strategies as we consider sirtuin activation as a part of a multifaceted approach to restoring mitochondrial health in neuronal populations.

Promoting mitochondrial biogenesis is essential for maintaining a healthy mitochondrial pool in neurons. Agents such as PGC-1α activators can stimulate the expression of genes involved in mitochondrial biogenesis [36]. PGC-1α is recognized as a master regulator that coordinates mitochondrial biogenesis and antioxidant defenses [37]. This strategy has emerged as a potential avenue for pharmaceuticals aiming to restore mitochondrial function, particularly in aging and neurodegenerative diseases.

Another innovative approach to restore mitochondrial function is through mitochondrial augmentation therapies, including stem cell-mediated transfer, isolated mitochondrial transplantation, and extracellular vesicle (EV)-based delivery.

Stem cells possess remarkable regenerative potential and can be utilized to enhance mitochondrial function in damaged neurons. The transplantation of stem cells has shown promise in various models of neurodegeneration. Recent studies suggest that stem cells can transfer healthy mitochondria to dysfunctional neuronal cells, thereby enhancing cellular health and restoring mitochondrial capacity. This method not only provides a direct source of functional mitochondria but can also promote neuroprotective factors beneficial for neuronal survival.

Isolated mitochondrial transplantation has gained traction as a method for rejuvenating dysfunctional mitochondria in neurons. This involves the delivery of healthy mitochondria directly to cells that exhibit impaired mitochondrial function. Research indicates successful mitochondrial transfer can restore energy production, reduce oxidative stress, and promote cell survival in neurodegenerative models [38]. For example, the delivery of exogenous mitochondria has been demonstrated to rescue functional impairment and promote sensory neuron regeneration in models of nerve damage [39]. This approach mimics cellular mechanisms utilized in physiological processes such as mitochondrial fusion and fission but applies them therapeutically.

EVs are naturally occurring nanoscale vesicles that facilitate intercellular communication and have been shown to carry various bioactive molecules, including proteins, lipids, and RNAs. EVs derived from stem cells or healthy donor cells can enhance mitochondrial function by delivering enzymatic components, signaling mediators, and even functioning mitochondria. This approach offers an innovative non-invasive strategy to improve neuronal function. Current research is exploring how engineered EVs can be tailored to target specific neuronal populations, enhancing their therapeutic potential in treating neurodegenerative diseases [40].

Recent advancements in neuromodulatory and photonic approaches provide novel means to modulate mitochondrial function and improve neuronal health through non-invasive techniques.

Photobiomodulation (PBM) refers to the use of low-level laser therapy, particularly in the red and near-infrared spectrum, to promote cellular repair and regeneration. Mechanistically, these wavelengths penetrate tissue and influence mitochondrial respiration by enhancing ATP synthesis and promoting mitochondrial biogenesis [41]. Studies have shown PBM can improve mitochondrial function, increase bioenergetics, and reduce oxidative stress in various models of neurodegeneration [42]. The safety and efficacy of this approach in clinical settings warrant further exploration, particularly in tandem with other therapeutic strategies for neurological disorders. A PBM-specific summary of biological targets, outcomes, and translational considerations is provided in Table 2.

Electrical stimulation can modulate neuronal activity and has been shown to enhance mitochondrial function. Techniques such as transcranial magnetic stimulation and deep brain stimulation exert effects on neuronal excitability and synchrony, which can influence mitochondrial function and efficiency [43]. Additionally, chemical modulators that target specific neuromodulatory pathways also hold promise for rejuvenating mitochondrial health. For instance, neurotransmitter modulation through selective agonists or antagonists may indirectly enhance mitochondrial function by optimizing neuronal signaling and energy demands during synaptic transmission [44].

These neuromodulatory approaches have the potential to act synergistically with other therapies, leading to a comprehensive strategy for restoring neuronal health by simultaneously addressing mitochondrial function and overall cellular dynamics.

Despite significant advancements in understanding mitochondrial dysfunction and its contributions to neurodegenerative diseases, the translatable therapeutic strategies aimed at mitochondrial rejuvenation face multifaceted barriers. This section discusses the delivery challenges for long-range neuronal networks, the timing of interventions concerning injury and disease progression, the integration of donor mitochondria with the host, and the necessity for standardized functional assessments beyond mere survival.

Delivering therapeutic agents to the distal parts of long-range neuronal networks poses considerable challenges. Neurons, especially those with extensive axonal projections, such as motor neurons and cortical pyramidal neurons, have unique architectures that require tailored approaches for effective drug delivery [45]. Traditional systemic administration of therapeutic molecules often struggles to achieve sufficient concentrations at synaptic terminals, which depend on mitochondrial dynamics for energy production and health.

Studies have shown that mitochondrial dysfunction can propagate from localized areas along the axonal length, where ineffective mitochondrial transport exacerbates the problem [46]. Thus, strategies for localized delivery of mitochondrial therapeutics via intranasal or intrathecal routes are currently under investigation. Novel methods, such as the formulation of drug carriers targeting mitochondrial pathways directly, hold potential but require further refinement to ensure efficient uptake and transport across neuronal membranes [47]. Overcoming the complexities of neuronal architecture will be crucial for the successful translation of mitochondrial therapies.

The timing of therapeutic interventions in the context of mitochondrial dysfunction is another critical factor influencing therapeutic efficacy. Interventions targeted at mitochondria must be strategically timed to coincide with critical windows of neurodegeneration or compensatory capacity. For instance, therapeutic strategies directed at enhancing mitophagy or mitochondrial biogenesis may be particularly effective when initiated early during neurodegeneration when compensatory mechanisms can still be activated.

In models of AD, evidence suggests that the restoration of mitochondrial function is more effective in earlier disease states compared to advanced stages characterized by extensive neuronal loss and irreversible damage [48]. Preclinical findings indicate that initiating therapies at pre-symptomatic stages or at early symptom appearances can significantly boost the therapeutic window for functional recovery [49]. Thus, a better understanding of disease progression and timely interventions may yield improved outcomes in clinical settings.

The integration of transplanted or transferred mitochondria from donor cells into host neurons raises significant questions regarding compatibility. Mitochondrial transplant therapies must ensure that donor mitochondria can efficiently integrate, complement the host cellular machinery, and become functionally operative within the recipient neuron [50]. Various intrinsic and extrinsic factors may influence the fate of transplanted mitochondria, including the degenerative state of host neurons and the compatibility of mitochondrial membranes and signaling pathways between donor and recipient cells.

Current studies utilize induced pluripotent stem cells and other cellular models to explore compatibility issues at a molecular level. Mitochondrial transfer experiments have indicated that differences in membrane potentials and mitochondrial dynamics can dictate the success of integration into host systems [51]. Optimization of mitochondrial donor sources to match recipient cell types or preconditioning recipient cells to enhance compatibility may represent viable strategies for improving therapeutic outcomes and ensuring efficacy [52].

Another major barrier to the successful translation of mitochondrial therapies remains the lack of standardized functional assessments. While improved survival rates among treated populations indicate therapeutic success, a comprehensive understanding of mitochondrial functionality and overall neuronal health is pivotal. Current assessments often focus on cell viability rather than robust mitochondrial measures like ATP production efficiency, mitochondrial bioenergetics, or the restoration of metabolic pathways.

To facilitate a rigorous evaluation of therapeutic interventions, standardized methods to assess mitochondrial function post-treatment must be developed. Functional assessments could include measuring ATP levels, evaluating mitochondrial dynamics, and quantifying ROS production alongside morphometric analyses of mitochondrial morphology. These assessments will provide critical data to correlate changes in mitochondrial performance with clinical outcomes in neurodegenerative diseases [53].

The exploration of mitochondrial rejuvenation therapies has gained prominence in addressing age-related decline and neurodegenerative diseases. With robust preclinical evidence supporting the functionality of various therapeutic interventions, the transition from laboratory settings to clinical applications holds significant promise. This is particularly relevant as the global aging population faces an increasing burden of neurodegenerative conditions.

Research focused on targeted mitochondrial therapeutics aims to mitigate age-related mitochondrial dysfunction, which is a critical factor in several neurodegenerative diseases, including AD, PD, and ALS. Literature indicates that dysfunctional mitochondria are implicated in the pathogenesis of these diseases, often leading to increased oxidative stress, mtDNA mutations, and diminished neuroprotection [45,54].

Aging is associated with a gradual decline in mitochondrial function; hence, interventions aimed at enhancing mitochondrial biogenesis, improving mitophagy, and boosting mitochondrial efficiency are particularly vital in older populations. For instance, studies have explored mitochondrial-targeting antioxidants that may relieve oxidative stress in neurodegeneration by protecting mitochondrial integrity and enhancing neuronal survival [55,56]. Additionally, activation of mitophagy has shown potential in alleviating the neurotoxic burden associated with the accumulation of damaged mitochondria, potentially improving cognitive outcomes in Alzheimer’s models [50].

To maximize therapeutic benefit, there is growing interest in combining mitochondrial repair strategies with regenerative therapies. This integrative approach can offer a dual mechanism—promoting recovery and resilience in neurons while also addressing mitochondrial dysfunction. Stem cell-based therapies can provide a viable means to restore functionality by replenishing damaged cells or enhancing the activity of resident neuronal stem cells.

Combining stem cell therapy with mitochondrial transfer protocols has demonstrated promise in preclinical studies, with evidence suggesting that healthy mitochondria can be delivered to distressed neuronal populations via stem cell exosomes or as isolated organelles [29]. Such strategies could facilitate more effective mitochondrial function restoration in diseases characterized by severe energy deficits. Engineering approaches that merge mitochondrial augmentation with regenerative techniques may further enhance neuronal repair and synaptic plasticity, amplifying the regenerative potential of the aging nervous system [57].

Advancements in engineering, including nanotechnology, gene delivery systems, and biomaterials, present exciting opportunities to enhance the targeted delivery of mitochondrial therapies. The development of nanoformulations capable of carrying mitochondrial-targeted therapeutics directly to neuronal tissues can minimize off-target effects and increase local concentrations at sites of mitochondrial dysfunction [58]. Moreover, innovative biomaterials could serve as scaffolds promoting neural growth while simultaneously integrating mitochondrial repair capabilities responsive to cellular needs [59].

Safety is paramount when developing these interventions; thus, ongoing efforts aim to ensure that mitochondrial augmentation therapies do not trigger excessive ROS production or other detrimental effects that could exacerbate existing neurodegenerative conditions. Engineering strategies that allow for precise temporal and spatial control over mitochondrial delivery could revolutionize clinical practices in neurodegeneration, enhancing therapy effectiveness while reducing potential side effects [60].

The landscape of mitochondrial therapeutic strategies is rich with opportunity, particularly in connection to age-related disorders and neurodegenerative diseases. By focusing on combinations of mitochondrial repair with regenerative approaches and leveraging engineering advancements, the potential for substantial clinical applications becomes increasingly tangible. Future studies will need to validate these strategies in clinical trials to confirm their safety, efficacy, and long-term benefits for patients facing neurodegeneration challenges [61].

Mitochondrial rejuvenation has the potential to serve as a transformative approach in mitigating age-related decline and neurodegenerative diseases, where mitochondrial dysfunction plays a pivotal role. By incorporating advanced therapies, such as small molecule modulations, mitochondrial augmentation techniques, and innovative neuromodulatory interventions, we can foster cellular health and restore mitochondrial performance crucial for neuronal function and survival. As we explore these therapeutic avenues, synchronizing interventions with regenerative therapies and leveraging emerging engineering approaches can significantly enhance the efficacy and safety of mitochondrial treatments.

Furthermore, understanding the intricacies of mitochondrial integration in host systems and addressing translational barriers will be vital for successful clinical applications. This necessitates a commitment to rigorous scientific validation through standardized functional assessments beyond mere survival metrics. Our collective efforts in elucidating the mechanisms underlying mitochondrial dysfunction and pioneering therapeutic strategies can pave the way for groundbreaking solutions aimed at restoring youthful characteristics to aging cells and tissues. Ultimately, these innovations will contribute to extending health span, alleviating the burden of neurodegenerative diseases, and improving the quality of life for aging populations.

References

1. Swerdlow RH. Mitochondria in neurodegeneration. In: Choi IY, Gruetter R, editors. Neural Metabolism In Vivo. Advances in Neurobiology, vol 4. Springer; 2012. p.885-906. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-1788-0_30.

2. Trinh D, Israwi AR, Arathoon LR, Gleave JA, Nash JE. The multi-faceted role of mitochondria in the pathology of Parkinson’s disease. J Neurochem 2021;156:715-52. doi: 10.1111/jnc.15154

3. Kann O, Kovács R. Mitochondria and neuronal activity. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2007;292:C641-57. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00222.2006

4. Wang Y, Xu E, Musich PR, Lin F. Mitochondrial dysfunction in neurodegenerative diseases and the potential countermeasure. CNS Neurosci Ther 2019;25:816-24. doi: 10.1111/cns.13116

5. Luo HM, Xu J, Huang DX, Chen YQ, Liu YZ, Li YJ, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction of induced pluripotent stem cells-based neurodegenerative disease modeling and therapeutic strategy. Front Cell Dev Biol 2022;10:1030390. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2022.1030390

6. Yao J, Irwin RW, Zhao L, Nilsen J, Hamilton RT, Brinton RD. Mitochondrial bioenergetic deficit precedes Alzheimer’s pathology in female mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009;106:14670-5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903563106

7. Sarkar S, Malovic E, Harishchandra DS, Ghaisas S, Panicker N, Charli A, et al. Mitochondrial impairment in microglia amplifies NLRP3 inflammasome proinflammatory signaling in cell culture and animal models of Parkinson’s disease. NPJ Parkinsons Dis 2017;3:30. doi: 10.1038/s41531-017-0032-2

8. Yan MH, Wang X, Zhu X. Mitochondrial defects and oxidative stress in Alzheimer disease and Parkinson disease. Free Radic Biol Med 2013;62:90-101. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.11.014

9. Libner CD, Salapa HE, Levin MC. The potential contribution of dysfunctional RNA-binding proteins to the pathogenesis of neurodegeneration in multiple sclerosis and relevant models. Int J Mol Sci 2020;21:4571. doi: 10.3390/ijms21134571

10. Noushad S, Sajid U, Ahmed S, Saleem Y. Oxidative stress mediated neurodegeneration; a cellular perspective. Int J Endorsing Health Sci Res 2019;7:192-212. doi: 10.29052/IJEHSR.v7.i4.2019.192-212

11. Alvarez-Mora MI, Podlesniy P, Riazuelo T, Molina-Porcel L, Gelpi E, Rodriguez-Revenga L. Reduced mtDNA copy number in the prefrontal cortex of C9ORF72 patients. Mol Neurobiol 2022;59:1230-7. doi: 10.1007/s12035-021-02673-7

12. Ignatenko O, Chilov D, Paetau I, de Miguel E, Jackson CB, Capin G, et al. Loss of mtDNA activates astrocytes and leads to spongiotic encephalopathy. Nat Commun 2018;9:70. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01859-9

13. Fišar Z, Hroudová J, Zvěřová M, Jirák R, Raboch J, Kitzlerová E. Age-dependent alterations in platelet mitochondrial respiration. Biomedicines 2023;11:1564. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines11061564

14. Mito T, Vincent AE, Faitg J, Taylor RW, Khan NA, McWilliams TG, et al. Mosaic dysfunction of mitophagy in mitochondrial muscle disease. Cell Metab 2022;34:197-208. e5. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2021.12.017

15. Castelli V, Benedetti E, Antonosante A, Catanesi M, Pitari G, Ippoliti R, et al. Neuronal cells rearrangement during aging and neurodegenerative disease: metabolism, oxidative stress and organelles dynamic. Front Mol Neurosci 2019;12:132. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2019.00132

16. Zong Y, Li H, Liao P, Chen L, Pan Y, Zheng Y, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction: mechanisms and advances in therapy. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2024;9:124. doi: 10.1038/s41392-024-01839-8

17. Millichap LE, Damiani E, Tiano L, Hargreaves IP. Targetable pathways for alleviating mitochondrial dysfunction in neurodegeneration of metabolic and non-metabolic diseases. Int J Mol Sci 2021;22:11444. doi: 10.3390/ijms222111444

18. Todorova V, Blokland A. Mitochondria and synaptic plasticity in the mature and aging nervous system. Curr Neuropharmacol 2017;15:166-73. doi: 10.2174/1570159x14666160414111821

19. Rumpf S, Sanal N, Marzano M. Energy metabolic pathways in neuronal development and function. Oxf Open Neurosci 2023;2:kvad004. doi: 10.1093/oons/kvad004

20. Berg RM, Møller K, Bailey DM. Neuro-oxidative-nitrosative stress in sepsis. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2011;31:1532-44. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2011.48

21. Alldred MJ, Lee SH, Stutzmann GE, Ginsberg SD. Oxidative phosphorylation is dysregulated within the basocortical circuit in a 6-month old mouse model of Down syndrome and Alzheimer’s disease. Front Aging Neurosci 2021;13:707950. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2021.707950

22. Teramoto S, Shimura H, Tanaka R, Shimada Y, Miyamoto N, Arai H, et al. Human-derived physiological heat shock protein 27 complex protects brain after focal cerebral ischemia in mice. PLoS One 2013;8:e66001. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066001

23. Stobart JL, Anderson CM. Multifunctional role of astrocytes as gatekeepers of neuronal energy supply. Front Cell Neurosci 2013;7:38. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2013.00038

24. Cherra SJ 3rd, Steer E, Gusdon AM, Kiselyov K, Chu CT. Mutant LRRK2 elicits calcium imbalance and depletion of dendritic mitochondria in neurons. Am J Pathol 2013;182:474-84. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.10.027

25. Massaad CA, Amin SK, Hu L, Mei Y, Klann E, Pautler RG. Mitochondrial superoxide contributes to blood flow and axonal transport deficits in the Tg2576 mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. PLoS One 2010;5:e10561. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010561

26. Liu X, Betzenhauser MJ, Reiken S, Meli AC, Xie W, Chen BX, et al. Role of leaky neuronal ryanodine receptors in stress-induced cognitive dysfunction. Cell 2012;150:1055-67. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.052

27. Weyemi U, Paul BD, Bhattacharya D, Malla AP, Boufraqech M, Harraz MM, et al. Histone H2AX promotes neuronal health by controlling mitochondrial homeostasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2019;116:7471-6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1820245116

28. Du F, Yu Q, Yan SS. PINK1 activation attenuates impaired neuronal-like differentiation and synaptogenesis and mitochondrial dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease trans-mitochondrial cybrid cells. J Alzheimers Dis 2021;81:1749-61. doi: 10.3233/JAD-210095

29. Cai Q, Zakaria HM, Simone A, Sheng ZH. Spatial parkin translocation and degradation of damaged mitochondria via mitophagy in live cortical neurons. Curr Biol 2012;22:545-52. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.02.005

30. Tang T, Hu LB, Ding C, Zhang Z, Wang N, Wang T, et al. Src inhibition rescues FUNDC1-mediated neuronal mitophagy in ischaemic stroke. Stroke Vasc Neurol 2024;9:367-79. doi: 10.1136/svn-2023-002606

31. De La Rossa A, Laporte MH, Astori S, Marissal T, Montessuit S, Sheshadri P, et al. Paradoxical neuronal hyperexcitability in a mouse model of mitochondrial pyruvate import deficiency. Elife 2022;11:e72595. doi: 10.7554/eLife.72595

32. Hees JT, Harbauer AB. Metabolic regulation of mitochondrial protein biogenesis from a neuronal perspective. Biomolecules 2022;12:1595. doi: 10.3390/biom12111595

33. Xu CC, Denton KR, Wang ZB, Zhang X, Li XJ. Abnormal mitochondrial transport and morphology as early pathological changes in human models of spinal muscular atrophy. Dis Model Mech 2016;9:39-49. doi: 10.1242/dmm.021766

34. Zheng YR, Zhang XN, Chen Z. Mitochondrial transport serves as a mitochondrial quality control strategy in axons: implications for central nervous system disorders. CNS Neurosci Ther 2019;25:876-86. doi: 10.1111/cns.13122

35. Bros H, Niesner R, Infante-Duarte C. An ex vivo model for studying mitochondrial trafficking in neurons. Methods Mol Biol 2015;1264:465-72. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-2257-4_38

36. Hori I, Harashima H, Yamada Y. Development of liposomes that target axon terminals encapsulating berberine in cultured primary neurons. Pharmaceutics 2023;16:49. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics16010049

37. Niescier RF, Chang KT, Min KT. Miro, MCU, and calcium: bridging our understanding of mitochondrial movement in axons. Front Cell Neurosci 2013;7:148. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2013.00148

38. Loss O, Stephenson FA. Developmental changes in trak-mediated mitochondrial transport in neurons. Mol Cell Neurosci 2017;80:134-47. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2017.03.006

39. Au NPB, Chand R, Kumar G, Asthana P, Tam WY, Tang KM, et al. A small molecule M1 promotes optic nerve regeneration to restore target-specific neural activity and visual function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2022;119:e2121273119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2121273119

40. Seager R, Lee L, Henley JM, Wilkinson KA. Mechanisms and roles of mitochondrial localisation and dynamics in neuronal function. Neuronal Signal 2020;4:NS20200008. doi: 10.1042/NS20200008

41. Maddison DC, Mattedi F, Vagnoni A, Smith GA. Analysis of mitochondrial dynamics in adult drosophila axons. Cold Spring Harb Protoc 2023;2023:75-83. doi: 10.1101/pdb.top107819

42. Mandal A, Wong HC, Pinter K, Mosqueda N, Beirl A, Lomash RM, et al. Retrograde mitochondrial transport is essential for organelle distribution and health in zebrafish neurons. J Neurosci 2021;41:1371-92. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1316-20.2020

43. Sabui A, Biswas M, Somvanshi PR, Kandagiri P, Gorla M, Mohammed F, et al. Decreased anterograde transport coupled with sustained retrograde transport contributes to reduced axonal mitochondrial density in tauopathy neurons. Front Mol Neurosci 2022;15:927195. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2022.927195

44. Watters O, Connolly NMC, König HG, Düssmann H, Prehn JHM. AMPK preferentially depresses retrograde transport of axonal mitochondria during localized nutrient deprivation. J Neurosci 2020;40:4798-812. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2067-19.2020

45. Ma Q, Xin J, Peng Q, Li N, Sun S, Hou H, et al. UBQLN2 and HSP70 participate in Parkin-mediated mitophagy by facilitating outer mitochondrial membrane rupture. EMBO Rep 2023;24:e55859. doi: 10.15252/embr.202255859

46. McWilliams TG, Prescott AR, Montava-Garriga L, Ball G, Singh F, Barini E, et al. Basal mitophagy occurs independently of PINK1 in mouse tissues of high metabolic demand. Cell Metab 2018;27:439-49.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2017.12.008

47. Doccini S, Morani F, Nesti C, Pezzini F, Calza G, Soliymani R, et al. Proteomic and functional analyses in disease models reveal CLN5 protein involvement in mitochondrial dysfunction. Cell Death Discov 2020;6:18. doi: 10.1038/s41420-020-0250-y

48. Yuan P, Song F, Zhu P, Fan K, Liao Q, Huang L, et al. Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase 1-mediated defective mitophagy contributes to painful diabetic neuropathy in the db/db model. J Neurochem 2022;162:276-89. doi: 10.1111/jnc.15606

49. Pérez MJ, Ivanyuk D, Panagiotakopoulou V, Di Napoli G, Kalb S, Brunetti D, et al. Loss of function of the mitochondrial peptidase PITRM1 induces proteotoxic stress and Alzheimer’s disease-like pathology in human cerebral organoids. Mol Psychiatry 2021;26:5733-50. doi: 10.1038/s41380-020-0807-4

50. Xie C, Zhuang XX, Niu Z, Ai R, Lautrup S, Zheng S, et al. Amelioration of Alzheimer’s disease pathology by mitophagy inducers identified via machine learning and a cross-species workflow. Nat Biomed Eng 2022;6:76-93. doi: 10.1038/s41551-021-00819-5

51. Fang EF, Hou Y, Palikaras K, Adriaanse BA, Kerr JS, Yang B, et al. Mitophagy inhibits amyloid-β and tau pathology and reverses cognitive deficits in models of Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Neurosci 2019;22:401-12. doi: 10.1038/s41593-018-0332-9

52. Tian S, Yan S, Meng Z, Sun W, Yan J, Huang S, et al. Widening the lens on prothioconazole and its metabolite prothioconazole-desthio: aryl hydrocarbon receptor-mediated reproductive disorders through in vivo, in vitro, and in silico studies. Environ Sci Technol 2022;56:17890-901. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.2c06236

53. Doxaki C, Palikaras K. Neuronal mitophagy: friend or foe? Front Cell Dev Biol 2021;8:611938. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2020.611938

54. Zhong W, Rao Z, Xu J, Sun Y, Hu H, Wang P, et al. Defective mitophagy in aged macrophages promotes mitochondrial DNA cytosolic leakage to activate STING signaling during liver sterile inflammation. Aging Cell 2022;21:e13622. doi: 10.1111/acel.13622

55. Hsieh CH, Shaltouki A, Gonzalez AE, Bettencourt da Cruz A, Burbulla LF, St Lawrence E, et al. Functional impairment in Miro degradation and mitophagy is a shared feature in familial and sporadic Parkinson’s disease. Cell Stem Cell 2016;19:709-24. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2016.08.002

56. Wang W, Ma X, Bhatta S, Shao C, Zhao F, Fujioka H, et al. Intraneuronal β-amyloid impaired mitochondrial proteostasis through the impact on LONP1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2023;120:e2316823120. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2316823120

57. Lee Y, Kim M, Lee M, So S, Kang SS, Choi J, et al. Mitochondrial genome mutations and neuronal dysfunction of induced pluripotent stem cells derived from patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Cell Prolif 2022;55:e13274. doi: 10.1111/cpr.13274

58. Palomo GM, Granatiero V, Kawamata H, Konrad C, Kim M, Arreguin AJ, et al. Parkin is a disease modifier in the mutant SOD1 mouse model of ALS. EMBO Mol Med 2018;10:e8888. doi: 10.15252/emmm.201808888

59. Qu X, Pan P, Cao S, Ma Y, Yang J, Gao H, et al. Immp2l deficiency induced granulosa cell senescence through STAT1/ATF4 mediated UPRmt and STAT1/(ATF4)/HIF1α/BNIP3 mediated mitophagy: prevented by enocyanin. Int J Mol Sci 2024;25:11122. doi: 10.3390/ijms252011122

Figure 1.

Mitochondrial dysfunction pathways leading to neuronal loss and corresponding therapeutic strategies. Metabolic therapies, mitochondrial transplantation, stem-cell/EV approaches, PBM, and TMS target mitochondrial repair and neuroprotection. ATP, adenosine triphosphate; ROS, reactive oxygen species; mPTP, mitochondrial permeability transition pore; DAMPs, damage-associated molecular patterns; NAD+, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide; PBM, photobiomodulation; TMS, transcranial magnetic stimulation; EVs, extracellular vesicles.

Table 1.

Emerging therapeutic strategies for mitochondrial rejuvenation in neural dysfunction

NAD+, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide; EV, extracellular vesicle; PBM, photobiomodulation; ROS, reactive oxygen species; TNT, tunneling nanotube; ETC, electron transport chain; ATP, adenosine triphosphate; NMN, nicotinamide mononucleotide; NR, nicotinamide riboside; NAC, N-acetylcysteine; MSC, mesenchymal stem cell; LED, light emitting diode; TMS, transcranial magnetic stimulation; DBS, deep brain stimulation.

Table 2.

PBM-based strategies for mitochondrial rejuvenation in neural dysfunction

-

METRICS

-

- 0 Crossref

- 0 Scopus

- 238 View

- 10 Download

- ORCID iDs

-

Celine Abueva

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8402-7838 - Related articles

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Download Citation

Download Citation Print

Print