Modern tools for taste: a multimodal approach to gustatory function

Article information

Abstract

Taste plays a vital role in dietary behavior, nutritional status, and quality of life, yet gustatory dysfunction remains underrecognized in clinical practice. This issue is especially relevant among aging populations, patients undergoing ear, nose, and throat surgeries, and individuals recovering from post-viral syndromes such as coronavirus disease (COVID-19). Conventional assessment methods rely on subjective self-reporting, limiting diagnostic accuracy and early intervention. This review presents a comprehensive, multimodal framework for objectively evaluating taste function by integrating electrophysiological techniques, neuroimaging modalities, and emerging wearable tools. Electrogustometry offers direct assessment of peripheral taste nerve responses, while functional magnetic resonance imaging, magnetoencephalography, positron emission tomography, and functional near-infrared spectroscopy provide complementary insights into cortical taste processing. These methods capture both real-time activity and longer-term metabolic changes linked to gustatory function. The approach is further enhanced by artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning, which enable large-scale data integration, predictive modeling, and personalized treatment strategies. Applications span diverse clinical settings, including pre- and postoperative monitoring, COVID-19 recovery, and clinical trials for regenerative and neuromodulatory therapies. A proposed clinical workflow emphasizes longitudinal tracking, standardization, and AI-enhanced analytics. Together, these advancements pave the way for more precise diagnosis, individualized care, and translational research in gustatory neuroscience and sensory medicine.

Introduction

Taste function significantly influences human health, affecting nutritional intake, dietary choices, and the overall enjoyment of food. Humans perceive five basic tastes, sweet, salty, sour, bitter, and umami, which link to various physiological and psychological responses. Taste extends beyond enjoyment; it ensures balanced diets and adequate nutrition, particularly in vulnerable populations such as older adults and those with medical conditions. Additionally, changes in taste perception can indicate diseases like neurodegenerative disorders, metabolic conditions, and infections such as coronavirus disease (COVID-19), underscoring the critical need for accurate taste assessment [1,2].

In otolaryngology, particularly ear, nose, and throat (ENT) surgery, clinicians recognize the importance of assessing taste function. Surgical interventions involving the middle ear, parotid glands, tonsils, or thyroid glands risk damaging nerves or altering taste pathways due to their close anatomical proximity. Such surgeries may inadvertently impair taste, causing complications like dysgeusia or ageusia. Thus, effective preoperative assessment and postoperative monitoring are essential to mitigate risks of taste dysfunction [3,4].

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the prev-alence and clinical importance of taste dysfunction, with studies reporting up to 43.93% of COVID-19 patients experiencing altered taste. Many patients report ageusia independently of olfactory loss, raising concerns about the long-term nutritional impact on recovering individuals and emphasizing the complexity of taste assessment in clinical practice [5,6]. Additionally, taste dysfunction caused by medical treatments or medications (iatrogenic dysgeusia) increasingly concerns healthcare providers, particularly in elderly patients experiencing polypharmacy and chronic health condition [3].

Despite recognizing the clinical importance of taste dysfunction, healthcare providers urgently need objective, multimodal monitoring methods. Current subjective assessments are limited by variability and individual symptom interpretation. Combining electrophysiological techniques, advanced imaging, and sensory evaluations can provide comprehensive and objective assessments, helping clinicians better understand taste disorders and enabling personalized interventions to improve patient nutrition and quality of life [7,8].

Thus, adopting multimodal gustatory neuromonitoring represents a significant advancement in taste evaluation, combining the strengths of diverse methods to enhance clinical outcomes. This approach is particularly relevant given the rising incidence of taste dysfunction associated with COVID-19 and its broader health implications. Ongoing research and clinical experience support developing robust, evidencebased strategies to assess and address taste dysfunction comprehensively [9]. As the understanding of taste dysfunction evolves, so too must the approaches employed to monitor and address these complex sensory impairments.

Anatomy and Mechanics of the Gustatory System

Peripheral Components

The peripheral gustatory system initiates taste perception by detecting stimuli at the oral level. Taste buds, which are specialized sensory structures located primarily on the tongue, contain taste receptor cells that transduce chemical signals into neural impulses. These taste buds are distributed in specific regions of the tongue, including the anterior portion, primarily innervated by the facial nerve (CN VII) via the chorda tympani branch, and the posterior portion, which receives innervation from the glossopharyngeal nerve [10,11]. Furthermore, the vagus nerve (CN X) contributes to taste perception by innervating taste buds in areas such as the epiglottis and the pharynx [10,11]. The architecture of the tongue, including fungiform, foliate, and circumvallate papillae, supports the functionality of the gustatory system by housing these taste buds and varying the density of sensory receptors across different regions [12,13].

The neuronal pathways involved in taste perception initiate in the taste receptor cells within the taste buds. These cells communicate with primary afferent nerve fibers, crucial for transmitting taste information towards the brainstem structures, primarily the nucleus of the solitary tract (NST). The NST functions as the initial relay station for taste signals before these impulses are conveyed to higher processing centers. Thermal and mechanical sensations, transmitted via the trigeminal pathway, also activate the NST, reinforcing the multisensory nature of taste perception [14,15]. Pathological conditions, such as neurological impairments, can affect these peripheral components, leading to taste dysfunction in various clinical scenarios, including post-surgical outcomes in ENT procedures [16].

Central Pathways in Gustation

The central pathways of the gustatory system extend from the NST to the thalamus and ultimately reach the gustatory cortex. From the NST, taste signals ascend to the ventroposteromedial nucleus of the thalamus, which relays the information to higher cortical centers. These include the insular cortex and the orbitofrontal cortex (OFC), where complex aspects of taste are processed. The NST is pivotal for processing taste information since it receives input from cranial nerves and houses first-order gustatory neurons [9,17,18]. Recent studies emphasize the thalamic role not merely as a relay but also as a processor of taste information, incorporating aspects of both sensory and emotional responses to taste stimuli [19].

Upon reaching the gustatory cortex, the processing advances to more complex dimensions such as flavor perception, which is influenced by integrated inputs from the olfactory system, providing context to taste experiences [18,20]. The OFC is particularly significant for evaluating the hedonic aspects of taste, intertwining cognitive assessments with gustatory processing [11,16]. The interconnected pathways that connect these structures indicate a highly organized network that shapes how taste perception is molded by both direct sensory input and additional contextual stimuli, underscoring the dynamic nature of gustatory processing and its behavioral outcomes [15,20].

Cross-modal Integration of the Gustatory System

Cross-modal integration is a critical aspect of the gustatory system, where taste is not processed in isolation but interacts with other sensory modalities. This interaction is especially evident in the integration of gustatory stimuli with olfactory and somatosensory inputs, such as those derived from the trigeminal system [21]. The interplay between taste and smell is well-documented, with studies revealing that a significant portion of flavor perception arises from olfactory inputs that complement the basic taste qualities detected on the tongue. The olfactory system enhances taste quality, allowing for the discrimination of complex flavor profiles that are fundamental to the human eating experience.

Somatosensory feedback provided by the trigeminal system also influences the perception of taste, with sensations such as temperature or irritation modifying the overall gustatory experience. For example, the spiciness of chili or the cooling effect of menthol activates trigeminal pathways, adding sensory depth to taste perception. This interaction is essential for holistic flavor interpretation and plays a role in guiding food preferences and dietary behaviors [20.21].

Additionally, research has identified neural mechanisms supporting these cross-modal interactions, reinforcing that the gustatory cortex operates within a broader sensory network. Understanding how these inputs converge in higher-order brain regions provides valuable insights into flavor perception and the mechanisms underlying taste disorders in conditions such as COVID-19. This multifaceted view underscores the importance of integrated sensory processing in both research and clinical applications [22].

Imaging-Based Approaches

Functional Activation of Gustatory Cortices: fMRI and MEG

Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and magnetoencephalography (MEG) are widely used neuroimaging techniques that map the brain's response to taste stimuli. fMRI detects hemodynamic changes, allowing visualization of blood oxygenation-level dependent signals associated with neural activation. During taste stimulation, fMRI studies consistently highlight activation in the insular cortex and OFC, regions known for processing taste quality and hedonic value [23]. The insula serves as the primary gustatory cortex and plays a key role in integrating interoceptive information, while the OFC contributes to the evaluative and reward-related aspects of taste [24].

MEG complements fMRI by capturing real-time magnetic fields generated by neuronal activity, offering superior temporal resolution. This makes it possible to observe the timing and sequence of taste processing in the brain [25]. When used together, fMRI and MEG provide a more complete picture of gustatory cortical dynamics, linking spatial patterns of activation with their temporal progression. This combination helps reveal how gustatory signals evolve across neural networks, and how different taste qualities are processed.

Bedside-Compatible Monitoring: fNIRS and PET

Functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) and positron emission tomography (PET) offer additional tools for assessing cortical activity during gustatory processing, especially in clinical or bedside settings. fNIRS is a portable, non-invasive technique that measures changes in oxygenated and deoxygenated hemoglobin in cortical regions, capturing functional responses to taste stimuli. Its flexibility and accessibility make it particularly valuable for evaluating taste perception in populations with mobility or health limitations [26,27]. Recent advancements in fNIRS technology have paved the way for integrating this method into practical clinical settings, allowing for continuous monitoring during taste stimulus exposure [28].

PET provides insights into metabolic brain activity and is useful in detecting functional changes related to gustatory dysfunction in conditions such as neurodegenerative diseases. It can identify altered glucose metabolism in gustatory regions like the insula and OFC. However, PET's higher cost and exposure to ionizing radiation limit its routine use [29].

Recent studies support the use of combined fNIRS and PET for complementary insights, with fNIRS offering high temporal flexibility and PET providing deep metabolic context [30,31]. These hybrid imaging strategies are particularly promising for clinical studies, where tracking treatment response or disease progression is critical.

Toward Multimodal Integration in Taste Neuroimaging

Each imaging modality provides unique insights into gustatory function, wherein fMRI and PET capture spatial and metabolic patterns, MEG offers precise temporal information, and fNIRS enables bedside-friendly monitoring. Together, they support a more comprehensive understanding of how the brain processes taste. Integrating findings across modalities allows clinicians and researchers to correlate peripheral taste stimulation with real-time brain activity, facilitating improved diagnosis and treatment planning.

Emerging research increasingly supports multimodal imaging strategies, combining tools like fMRI and fNIRS or MEG and PET to bridge the gap between brain function, sensory perception, and behavioral outcomes. These integrated approaches are essential for advancing our knowledge of taste-related neural processing, particularly in clinical populations affected by surgery, aging, or infection-related taste disorders such as those seen in COVID-19. A comparative overview of these modalities, including their strengths, limitations, and clinical applications, is summarized in Table 1.

Sensory and Gustatory Evaluation Methods

Taste Strips and Threshold Testing

Taste strips and threshold testing are widely used clinical tools that help assess the function and sensitivity of the gustatory system. Taste strips are paper strips impregnated with known concentrations of basic taste compounds (sweet, salty, sour, bitter, and umami), which are applied to the tongue to determine taste recognition ability. These tests are simple, cost-effective, and easy to standardize, making them useful for both research and clinical screening [32].

Threshold testing measures the lowest concentration of a taste stimulus a person can detect or correctly identify. When administered systematically, these tests help identify early signs of gustatory dysfunction. Clinical studies have shown that selfreported taste loss often overestimates actual dysfunction, reinforcing the importance of using validated sensory methods. Standardized administration protocols and proper evaluator training further enhance reliability and reproducibility [32-34].

Whole-Mouth Gustatory Test

Whole-mouth gustatory testing involves the use of liquid tastant solutions presented to the entire oral cavity, offering a more ecologically valid representation of real-world taste perception [33,34]. This method assesses detection and recognition thresholds, as well as intensity ratings, providing a comprehensive view of gustatory sensitivity.

Compared to localized tests, whole-mouth methods can capture broader impairments across different oral regions. This approach is especially valuable for assessing generalized taste loss due to systemic diseases, medication side effects, or viral infections such as COVID-19. Studies have also shown promising correlations between whole-mouth test results and neural responses in gustatory brain regions, making it a useful tool in conjunction with neuroimaging techniques [35,36].

Isolating Taste from Other Sensory Modalities

One of the central challenges in gustatory assessment is separating pure taste perception from the influence of smell and trigeminal (somatosensory) inputs [37]. These modalities often activate simultaneously during eating and drinking, contributing to the overall perception of flavor. For instance, olfactory input enhances taste complexity, while the trigeminal system conveys texture, temperature, and irritation (e.g., spiciness or cooling effects) [38].

To improve test specificity, researchers have introduced masking techniques to suppress olfactory or trigeminal cues during gustatory evaluation. These approaches aim to isolate taste stimuli and avoid confounding sensory contributions. Although complete isolation is challenging, incorporating such controls allows for more accurate analysis of taste perception, particularly in clinical populations where multisensory integration may be disrupted.

Refining these methods and combining them with neurophysiological or neuroimaging tools enables a deeper understanding of how isolated taste signals are processed, supporting more targeted diagnosis and treatment of gustatory disorders [39].

Toward a Multimodal Gustatory Monitoring Framework

Multimodal Integration of Gustatory Monitoring Techniques

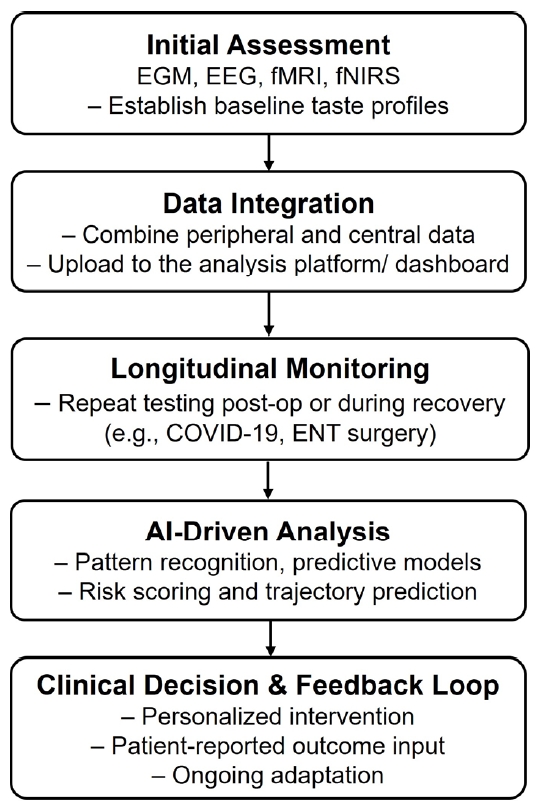

A comprehensive gustatory monitoring framework integrates electrogustometry (EGM), fMRI, and electroencephalography (EEG). EGM measures peripheral taste nerve responses by recording electrical activity in response to applied taste stimuli, offering objective insights into the functional integrity of taste pathways. fMRI and EEG provide complementary perspectives by visualizing brain activation patterns and electrical activity associated with taste perception. This combined approach allows clinicians and researchers to link peripheral taste responses with central processing dynamics, thereby enabling more accurate diagnosis and characterization of gustatory disorders. The proposed clinical workflow for integrating electrophysiological, neuroimaging, and AI-based tools is illustrated in Figure 1.

Pre- and Postoperative Monitoring of Taste Function

Multimodal monitoring proves especially valuable in clinical scenarios involving surgeries that risk disrupting taste pathways, such as ENT procedures affecting the parotid glands, tonsils, or thyroid. Preoperative assessments using EGM and neuroimaging can establish baseline profiles of taste function, helping predict postoperative outcomes. Postoperatively, repeated evaluations allow clinicians to track recovery trajectories and distinguish between transient disruptions and long-term deficits in gustatory function. These data support timely interventions and individualized rehabilitation strategies to restore or compensate for taste loss, enhancing patient quality of life.

Gustatory Recovery Monitoring and Broader Clinical Applications

The COVID-19 pandemic has increased awareness of gustatory dysfunction, particularly cases of prolonged or isolated ageusia. Multimodal monitoring tools such as EGM, fMRI, and EEG provide valuable insights into the progression and recovery of taste function in affected individuals by capturing both peripheral and central nervous system responses. These tools help clinicians assess not only the presence of dysfunction but also the underlying neurophysiological mechanisms driving persistent symptoms.

This monitoring framework is also relevant to broader clinical contexts. In aging populations, agerelated degeneration of taste receptors and nerves can reduce dietary satisfaction and contribute to malnutrition. Similarly, polypharmacy and chronic conditions often found in elderly or medically complex patients may disrupt normal gustatory signaling. Neurodegenerative diseases like Parkinson's and Alzheimer's also affect cortical taste processing, making accurate monitoring essential for early symptom detection and nutritional management.

Furthermore, this integrative approach is well-suited for use in clinical trials evaluating regenerative therapies or neurostimulatory interventions aimed at restoring taste function. By linking patient-reported outcomes with objective physiological and neural markers, clinicians can more precisely evaluate treatment efficacy and track response over time.

The incorporation of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning enhances the utility of this framework. These technologies enable automated pattern recognition across multimodal datasets, support early identification of dysfunction trends, and help predict long-term recovery trajectories. Combined with wearable and portable platforms currently under development, this approach supports real-time, patientspecific interventions.

Ultimately, multimodal gustatory neuromonitoring supports a personalized medicine approach to taste dysfunction. It facilitates early detection, targeted intervention, and ongoing evaluation, offering meaningful improvements in clinical care and quality of life for individuals experiencing altered taste perception. Table 2 outlines key clinical scenarios where multimodal gustatory monitoring provides measurable benefits, illustrating its relevance across disease contexts and treatment pipelines.

Challenges and Future Directions

Standardization and Validation of Gustatory Assessment Protocols

One of the most pressing challenges in advancing gustatory monitoring is the lack of standardized, validated protocols. Current tools such as EGM, EEG, and imaging-based techniques often vary in methodology, sensitivity, and evaluation criteria. This inconsistency hampers the comparability of clinical and research findings and impedes the development of normative benchmarks. Standardization is especially critical given the substantial inter-individual variability in taste perception influenced by age, sex, genetics, and comorbidities. Establishing validated, reproducible testing frameworks would support the generation of population-level reference data and ensure clinical reliability.

Balancing Accuracy with Patient Comfort in Gustatory Assessments

Another key challenge lies in balancing the diagnostic accuracy of gustatory assessment techniques with their invasiveness and clinical practicality. While EGM offers direct, quantitative measurements of taste nerve function, it can be uncomfortable for some patients. Conversely, neuroimaging modalities such as fMRI and PET, although informative, are resource-intensive and less accessible in routine clinical settings. Emerging solutions include wearable EEG and fNIRS devices that offer non-invasive, real-time data collection with greater feasibility. Future research should focus on optimizing these tools for broader implementation, particularly in primary care and rehabilitation contexts.

Addressing Inter-individual Variability and Developing Normative Data

The considerable variability in taste perception and its neural representation poses both a scientific and clinical challenge. Factors such as genetic makeup, disease state, medication use, and cultural background contribute to diverse taste experiences. In neuroimaging studies, this results in heterogeneity in cortical activation patterns even under similar stimulation. There is a critical need for large-scale studies to establish normative baselines that account for such variability. Expanding demographic representation in research will allow more accurate interpretation of results and support the development of personalized interventions.

Future Integration of AI and Wearable Technologies

AI and wearable neurotechnologies represent promising tools for the future of gustatory monitoring. AI can assist in analyzing large, complex datasets by identifying subtle patterns and classifying types of taste dysfunction. Predictive modeling may help anticipate long-term outcomes and guide early interventions. Meanwhile, wearable systems incorporating sensors and portable EEG or fNIRS units can enable continuous gustatory monitoring outside clinical environments. Together, these advances promise to enhance the accessibility, personalization, and diagnostic power of taste assessments across diverse populations.

Conclusion

Multimodal gustatory neuromonitoring represents a transformative approach to understanding and managing taste dysfunction. By integrating electrophysiological tools like EGM, neuroimaging modalities such as fMRI and EEG, and emerging wearable technologies, clinicians and researchers can achieve a more comprehensive view of both peripheral and central aspects of gustatory processing. This multimodal strategy bridges the gap between subjective reports and objective data, enhancing diagnostic accuracy and guiding targeted interventions.

The convergence of diverse methodologies allows for tailored assessments in various clinical contexts, from pre- and post-operative monitoring in ENT surgeries to tracking recovery in COVID-19 survivors or individuals with neurodegenerative conditions. Realtime monitoring capabilities and AI-driven data analysis further support dynamic, individualized care pathways that align with the principles of precision medicine.

Looking forward, broader adoption of standardized testing protocols, expanded normative data, and the integration of AI and wearable systems will be critical to scaling this approach across clinical and research settings. Multimodal gustatory monitoring not only enhances our understanding of taste function but also supports early detection, patient-specific management, and continuous outcome evaluation, ultimately improving nutritional health and quality of life for diverse populations affected by taste disorders.

Notes

Funding

None.

Conflict of Interest

Celine Abueva is an editorial board member of the journal, but was not involved in the review process of this manuscript. Otherwise, there is no conflict of interest to declare.

Data Availability

None.

Author Contributions

All work was done by CA.