Electrophysiological biomarkers in neurodegenerative diseases: recent advances and clinical implications

Article information

Abstract

Electrophysiological biomarkers are critical tools for understanding and diagnosing major neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), and Huntington's disease. These biomarkers reveal early disruptions in neural circuits before overt clinical symptoms become apparent. In Alzheimer's disease, electrophysiological changes such as hippocampal hyperexcitability, impaired synaptic plasticity, and disrupted theta-gamma oscillations strongly correlate with cognitive deficits and underlying pathological features like amyloid-beta and tau aggregation. Parkinson's disease is characterized by abnormal burst firing patterns of dopaminergic neurons, exaggerated beta oscillations within basal ganglia circuits, and impaired cortico-striatal synaptic plasticity, reflecting the effects of dopamine depletion and alpha-synuclein pathology. ALS demonstrates distinct electrophysiological features, notably hyperexcitability of motor neurons and impaired neuromuscular transmission, linked to mutant superoxide dismutase 1 and transactive response DNAbinding protein-43. Huntington's disease shows pronounced dysfunction in striatal circuits, marked by excitationinhibition imbalance and altered glutamatergic signaling, driven by mutant huntingtin toxicity. Collectively, these electrophysiological biomarkers provide early diagnostic insights and deepen our understanding of disease mechanisms, paving the way for targeted therapeutic interventions and improving the management and prognosis of neurodegenerative diseases.

Introduction

Neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer's disease (AD), Parkinson's disease (PD), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), and Huntington's disease (HD) are characterized not only by progressive cell loss but also by early functional disturbances in neural circuits. Electrophysiological biomarkers - measurable electrical patterns in the brain or nerves - have emerged as powerful indicators of these circuit dysfunctions. In some cases, aberrant neural activity precedes overt pathology: for example, in AD, network hypersynchrony and oscillatory rhythm alterations can be detected decades before clinical onset, and such early network changes predict future neurodegeneration [1]. Animal models of neurodegenerative diseases have been invaluable for identifying these electrophysiological signatures and dissecting their underlying mechanisms. Because they allow invasive and longitudinal recording at multiple scales (from single-neuron firing to large-scale electroencephalogram, electroencephalogram (EEG), oscillations), animal studies provide mechanistic insights linking electrophysiological abnormalities to molecular and cellular pathology.

Key electrophysiological biomarkers discussed in this review include:

• EEG and Local Field Potentials: Changes in brain oscillations (e.g., slowing of rhythms, loss of synchronization, or appearance of epileptiform spikes) have been observed in models of AD and HD, while exaggerated rhythmic activity in specific bands (such as beta oscillations) is a hallmark of PD models [2].

• Neuronal Firing Patterns: Altered firing rates and patterns (bursting, synchronization, or hyperexcitability) occur in affected circuits. For instance, cortical and hippocampal neurons in AD models can become hyperexcitable [3], dopaminergic network neurons in PD shift to bursty, oscillationlocked firing [2], and motor neurons in ALS models often show early hyperexcitability [4].

• Synaptic and Network Plasticity: Long-term potentiation (LTP) and depression (LTD) - measures of synaptic strength - are disrupted in several models. AD mice exhibit impaired LTP in hippocampal circuits as pathology accumulates [5], and HD models show progressive deficits in both short-term and long-term synaptic plasticity well before neuronal death [6].

By focusing on animal model findings, we can interpret how such electrophysiological changes contribute to disease mechanisms. Below, we review mechanistic insights gleaned from electrophysiological studies in animal models of the four major neurodegenerative diseases - AD, PD, ALS, and HD - highlighting how these biomarkers illuminate pathological processes.

Alzheimer's Disease

Recent research has identified several electrophysiological alterations in AD that serve as potential biomarkers of network dysfunction. Transgenic mouse models of AD-including amyloid precursor protein/presenilin-1 (APP/PS1), Tg2576 (APP Swe), and 5XFAD mice - consistently show aberrant neural network activity reminiscent of AD pathology. Key findings include hippocampal hyperexcitability, synaptic plasticity impairments, and disruptions in oscillatory brain rhythms (particularly in the theta and gamma frequency ranges). These changes are closely linked to cognitive deficits and the underlying amyloid-β (Aβ) and tau pathology of AD, highlighting their relevance for disease mechanisms and biomarker development.

Hippocampal Hyperexcitability and Epileptiform Activity

Network Hyperexcitability: AD mouse models often exhibit excessive neuronal firing and hypersynchronous network activity in the hippocampus and cortex. For example, hAPP transgenic mice with high Aβ levels show spontaneous non-convulsive seizure activity in hippocampal and cortical circuits. This hyperexcitability is accompanied by compensatory sprouting of inhibitory GABAergic fibers and heightened synaptic inhibition in the dentate gyrus, yet overall results in synaptic plasticity deficits [7]. Similarly, Tg2576 mice display neuronal hyperexcitability and epileptiform EEG discharges early in life, even prior to extensive plaque deposition [8]. In APP/PS1 mice, the incidence of spontaneous seizures increases with rising Aβ plaque burden [9], indicating that amyloid pathology contributes directly to network overexcitation. Notably, in vivo two-photon calcium imaging in APP/PS1 models has revealed clusters of hippocampal cornu ammonis (CA) 1 neurons that become hyperactive even before amyloid plaque formation, correlating with soluble Aβ levels [10]. Acute lowering of Aβ can normalize this early hyperactivity, while exogenous A β can induce hyperexcitable firing in wild-type mice. These results identify hippocampal hyperexcitability as an early functional biomarker in AD models driven by soluble Aβ [8].

Epileptiform Discharges: The network hyperexcitability in AD models often manifests as epileptiform spikes or seizures. EEG recordings from hAPPJ20 (APP overexpressing) mice reveal recurrent hypersynchronous discharges, indicating subclinical seizure activity [11]. Intriguingly, these spikes tend to occur during periods of reduced gamma oscillation power [11], suggesting a breakdown of normal inhibitory rhythmic activity. Chronic network hyperactivity in AD mice has been linked to cognitive decline, akin to human AD patients where subclinical seizures are increasingly recognized. In fact, treating hAPP mice and APP23 mice with anti-epileptic drugs to suppress network overexcitation can reverse their synaptic and cognitive deficits [12], underscoring that epileptiform activity is not merely an epiphenomenon but a contributor to memory impairment. Conversely, reducing excitatory drive pharmacologically or genetically can prevent many Aβ-induced neuronal alterations [7]. These findings cement hippocampal hyperexcitability and epileptiform EEG activity as pathological biomarkers in AD models, linking excessive network activity to the memory deficits characteristic of the disease [7,12].

Synaptic Dysfunction and Impaired LTP

LTP Deficits: A hallmark of AD models is synaptic dysfunction, often evidenced by impaired LTP in the hippocampus. Transgenic mice overproducing Aβ consistently show deficits in LTP induction and maintenance that parallel their learning and memory impairments. In the Tg2576 model, for instance, LTP is completely abolished at the CA3-CA1 Schaffer collateral synapses, despite normal basal synaptic transmission [13]. Similarly, 5XFAD mice develop significant LTP impairments as early as 4 months of age, which worsen with advancing Aβ pathology [14]. Theta-burst stimulation fails to elicit normal potentiation in 5XFAD hippocampal slices, indicating an attenuation of synaptic plasticity that precedes overt cell death. These plasticity deficits are tightly coupled to memory problems in behavior - for example, spatial memory tasks are impaired in Tg2576 and 5XFAD mice at ages when CA1 LTP is deficient, linking synaptic plasticity failure to cognitive decline [13,14].

Mechanisms of Synaptic Impairment: Mechanistically, soluble Aβ oligomers are known to disrupt glutamatergic synapses and block LTP through multiple pathways (including N-Methyl-D-Aspartate (NMDA) receptor modulation and spine loss), while enhancing long-term depression. In AD models, Aβ -induced hyperexcitability itself may contribute to synaptic dysfunction by triggering compensatory inhibitory sprouting and alterations in dendritic structure that limit plasticity [15]. Tau pathology also plays a critical role in synaptic and network deficits: reducing endogenous tau levels in hAPP mice prevents the development of memory deficits and LTP impairment despite high Aβ levels [16]. Tau reduction likewise protects neurons from Aβ-induced excitotoxicity, suggesting that tau pathology is an important mediator of Aβ's synaptotoxic and neurotoxic effects. Conversely, tau abnormalities (as seen in tau transgenic mice) can themselves lead to hyperexcitability and synaptic loss, creating a vicious cycle. Overall, impaired LTP and related synaptic dysfunction are robust electrophysiological biomarkers in AD models that directly tie Aβ and tau pathology to the collapse of synaptic plasticity underlying learning and memory.

Disrupted Gamma Oscillations and Theta-Gamma Coupling

Gamma Rhythm Abnormalities: Gamma oscillations (roughly 30-80 Hz), which depend on intact inhibitory interneuron function, are often disrupted in AD. In APP transgenic mice, a reduction in gamma power and synchrony accompanies the emergence of epileptiform activity [11]. Verret et al. demonstrated that hAPP-J20 mice have impaired cortical and hippocampal gamma oscillations due to dysfunction of parvalbumin-positive (PV) interneurons, which normally coordinate fast rhythmic firing [11]. These mice showed reduced expression of the PV interneuron-specific Na_v1.1 sodium channel subunit (also observed in AD patient brains), leading to weakened inhibitory output. Strikingly, restoring Na_v1.1 levels in hAPP mice reinstated gamma oscillatory activity and greatly reduced network hypersynchrony and memory deficits [11]. This causally links gamma rhythm disruption with cognitive dysfunction in AD models: when gamma activity is normalized via improved interneuron function, learning and memory can recover. Consistently, other AD models (e.g. 5XFAD mice) exhibit early disturbances in gamma oscillation coherence along hippocampal circuits, even before significant neuron loss [17].

Theta-Gamma Coupling: Beyond isolated gamma or theta rhythm changes, AD models also show aberrant cross-frequency coupling, which is crucial for information processing. Theta (4-8 Hz) oscillations in the hippocampus normally modulate local gamma bursts (a phenomenon essential for memory encoding and retrieval). In several AD mouse lines, this theta-gamma coupling is altered early in the disease course. Notably, young TgCRND8 mice (carrying mutant APP) as young as 1 month old display significantly degraded theta-gamma phase-amplitude coupling in the hippocampal subiculum - a key output region - despite having barely any Aβ deposition [18]. Such coupling deficits were not present in even younger (15-day-old) animals, indicating that the network changes develop with the onset of Aβ -related pathology rather than purely genetic developmental effects. Likewise, 5XFAD mice in early stages show weakened synchronization between the entorhinal input (theta) and dentate gyrus network (gamma), evidenced by reduced phase-locking and coherence measures [17]. Because theta-gamma coupling is thought to underlie the temporal organization of memory ensembles, these disruptions provide a physiological basis for the memory fragmentation in AD. Importantly, the theta and gamma network disturbances often precede overt amyloid plaque accumulation or cognitive symptoms, underscoring their potential as early biomarkers. Indeed, they likely reflect the functional impact of soluble Aβ and subtle circuit remodeling before neurodegeneration is apparent.

Links to Cognitive Dysfunction and AD Pathology

The pathological electrophysiological changes in AD models are closely intertwined with cognitive impairment and the hallmark proteinopathies of AD (Aβ and tau). Hippocampal hyperexcitability - while initially arising as a compensatory response or early network symptom - can undermine the precision of neural coding, leading to memory deficits. In mice, excessive hippocampal activity has been shown to disrupt memory consolidation, and curbing this hyperactivity improves cognitive performance. Similarly, gamma oscillations and theta-gamma coupling are fundamental for learning; their disruption in AD impairs the coordination of neuronal ensembles during memory tasks. Restoration of normal oscillatory dynamics (for instance, via interneuron modulation in hAPP mice [19] or external stimulation paradigms) has proven effective in rescuing memory function, highlighting a causal relationship. On a molecular level, Aβ and tau pathologies drive these electrophysiological aberrations: Aβ oligomers can acutely depress synaptic plasticity and provoke network hyper-synchrony [8,16], while tau accumulation in dendrites amplifies neuronal excitability and network breakdown. Conversely, mitigating Aβ (e.g. with γ -secretase inhibitors) or tau (genetically or via immunotherapy) tends to normalize network activity and improve cognition. Thus, electrophysiological biomarkers like hyperexcitability, impaired LTP, and altered oscillations are not only correlates of AD pathology but also mechanistic links between amyloid/tau accumulation and cognitive decline. They offer valuable endpoints for evaluating therapeutic strategies and provide early indicators of neuronal dysfunction before irreversible neurodegeneration occurs [17,18].

Parkinson's Disease

PD involves characteristic disruptions of basal ganglia circuit activity due to nigrostriatal dopamine loss and protein aggregation pathology. Across PD models - including neurotoxin-induced models (1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) -treated rodents and 6-hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA) lesions) and genetic α-synuclein overexpression mice - investigators have identified several electrophysiological biomarkers of circuit dysfunction. Prominent among these are abnormal burst firing of substantia nigra pars compacta (SNc) dopaminergic neurons, pathological β-band oscillations in basal ganglia networks, and impaired cortico-striatal synaptic plasticity. Below, we summarize these abnormalities and their mechanistic links to dopamine depletion and α -synuclein aggregation.

Burst Firing in SNc Dopaminergic Neurons

In healthy conditions, SNc dopaminergic neurons typically exhibit autonomous pacemaking with relatively regular firing. PD models, however, show a shift toward irregular, bursty firing patterns in surviving dopamine neurons. In 6-OHDA-lesioned rats, for example, the remaining SNc neurons maintain nearnormal firing at moderate dopamine loss but begin to exhibit increased firing rates and burst discharges as depletion becomes severe [20]. Hollerman and Grace noted that only after extreme (>96%) striatal dopamine depletion do SNc neurons show significant increases in firing rate and burst activity, suggesting a compensatory recruitment of burst firing in response to profound dopamine loss [20]. Similarly, in MPTP-treated parkinsonian animals, basal ganglia output neurons shift to bursty firing modes. Pallidal neurons in MPTP-lesioned primates fire in high-frequency bursts rather than tonic patterns [21], and an increased incidence of burst firing is also observed in subthalamic nucleus (STN) neurons under dopamine-depleted conditions [22]. These burst firing patterns are correlated with motor deficits of parkinsonism [22]. Notably, burstiness in SNc dopaminergic cells may also arise from intrinsic and network changes associated with PD. Loss of autoinhibitory dopamine signaling and aberrant synaptic inputs (e.g. hyperactive STN drive) likely contribute to transitioning SNc neurons into burst firing modes. In genetic PD models, there is evidence that early α-synuclein accumulation can dysregulate intrinsic excitability of SNc neurons. For instance, phosphatase and tensin homolog-induced putative kinase 1 or α-synuclein mutant mice show dopamine neurons that are hyperexcitable and prone to irregular firing, linking proteinopathy to altered pacemaker stability [23,24]. Thus, abnormal burst firing in SNc dopamine neurons is a hallmark of PD pathophysiology, reflecting both the loss of normal dopamine-mediated regulatory feedback and potential toxic effects of α-synuclein on neuronal firing homeostasis.

Aberrant Beta Oscillations in Basal Ganglia Circuits

One of the most distinctive network-level abnormalities in PD is the emergence of exaggerated beta-frequency (13-30 Hz) oscillations throughout the cortico-basal ganglia-thalamic loop. In patients with PD, local field potentials in the STN and cortex show heightened β oscillatory power that correlates with bradykinesia and rigidity [21]. Toxin-based PD models replicate this phenomenon. Dopamine-depleted 6-OHDA rats display excessive synchronous oscillations at β frequencies in the basal ganglia, especially during activated brain states [25]. Mallet et al. demonstrated that after dopamine lesion in rats, neurons in the external globus pallidus (GPe) become abnormally synchronized at 20 Hz, despite a reduction in their mean firing rates [25]. This aberrant synchrony extends across basal ganglia nodes: STN and GPe form a hyper-coupled network that can resonate in the β range, and such oscillatory coupling is also seen in MPTP-treated primates [22]. Increased population synchrony is a pervasive feature, with normally uncorrelated neighboring pallidal neurons firing in phase after dopamine loss. These β oscillations are not mere epiphenomena; they likely interfere with information coding in motor circuits. Mechanistically, dopamine depletion is a key trigger: removal of dopamine's stabilizing influence on striatal output and STN excitability permits the GPe-STN recurrent circuit to generate rhythmic burst oscillations [25]. Consistent with this, restoring dopamine tone (via Levodopa (L-DOPA) or dopaminergic grafts) suppresses β oscillations and ameliorates motor deficits [21]. Interestingly, mice overexpressing α -synuclein without overt dopamine loss do not exhibit the typical β hyper-oscillations. Lobb et al. found that 5-6 month old α-syn transgenic mice with motor impairment actually showed a slight decrease in β-band power (during active cortical states) and no emergence of synchronized burst firing in basal ganglia output neurons [24]. This contrasts with toxin models and suggests that highamplitude β oscillations in PD are principally a consequence of dopamine depletion-induced circuit imbalances, rather than solely α-synuclein aggregation. Nevertheless, in later stages of α-synuclein pathology when dopamine neurons do degenerate, β oscillopathy is expected to arise as in other PD models.

Cortico-Striatal Synaptic Plasticity Deficits

Long-term synaptic plasticity at cortico-striatal synapses - including LTP, LTD, and depotentiation - is critical for motor learning and action selection. PD and its models consistently show impairments in these forms of plasticity, implicating them as electrophysiological biomarkers. In dopamine-intact striatum, high-frequency cortical stimulation can induce LTP of excitatory transmission onto striatal medium spiny neurons, while low-frequency stimulation triggers LTD, and an established LTP can be erased by low-frequency stimulation (depotentiation). Dopamine depletion disrupts this bidirectional plasticity. In 6-OHDA-lesioned rats, the induction of striatal LTP/LTD is blunted or lost, reflecting "pathological plasticity" [26]. For example, Calabresi and colleagues showed that 6-OHDA lesions prevent the normal induction of both LTP and LTD in striatal slices, an effect attributable to the absence of dopamine receptor activation during the plasticity protocols. This deficit can be reversed by dopamine replacement: chronic L-DOPA treatment restores some forms of synaptic plasticity in lesioned rat [26]. However, improperly restored plasticity may underlie complications (e.g. L-DOPAinduced dyskinesias are associated with a selective loss of depotentiation in striatum). In genetic PD models, synaptic plasticity changes can precede cell loss. Mice overexpressing human α-synuclein show early cortico-striatal plasticity abnormalities despite intact nigrostriatal innervation. Watson et al. reported that transgenic α-syn mice have altered short-term plasticity (enhanced paired-pulse facilitation) and develop a unique presynaptic LTD at corticostriatal synapses that is absent in wild-type mice [27]. These mice also showed an exaggerated response to cAMP-elevating stimuli (forskolin), suggestive of aberrant cAMP/PKA signaling at synapses. Overall, elevated α-synuclein levels appear to dampen glutamate release and perturb the normal synaptic strengthening in striatum [27]. This synaptopathy in α-syn models may mimic early PD stages, wherein synaptic dysfunction and plasticity failure contribute to motor deficits before extensive cell death. Indeed, a function of normal α-syn is regulating synaptic vesicle trafficking and neurotransmitter release, and pathogenic α-syn oligomers can interfere with NMDA receptor-dependent forms of plasticity [23]. Thus, dopamine depletion and α-synuclein pathology converge on cortico-striatal synapses to impair the adaptive plasticity needed for smooth motor control.

Mechanistic Links to Dopamine Depletion and α-Synuclein

The above electrophysiological changes are interrelated consequences of dopamine loss and α -synuclein accumulation. Dopamine depletion is a primary driver of network dysfunction: it removes crucial modulatory inputs that normally stabilize firing patterns and coordinate activity. Loss of tonic D2-receptor inhibition in the indirect pathway leads to STN hyperactivity, which in turn promotes burst firing and β oscillatory entrainment in the STN-GPe loop. Likewise, without dopamine's facilitation of cortical inputs to the direct pathway, striatal neurons cannot induce LTP, and endocannabinoid-mediated LTD is compromised - locking basal ganglia circuits in a maladaptive state. In toxin-based models, these mechanisms explain the emergence of bursty, synchronized β activity that correlates with akinetic symptoms [22,25]. The fact that dopaminergic therapies and STN deep brain stimulation (which overrides intrinsic STN rhythms) can suppress β oscillations and reduce burst firing further supports the causative role of dopamine-dependent network changes in these abnormalities [21].

α-Synuclein aggregation, on the other hand, contributes both upstream and downstream of dopamine neuron loss. Intraneuronal α-syn aggregates (Lewy bodies) impair neuronal homeostasis through multiple mechanisms - mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and disrupted protein recycling - which can make SNc dopaminergic neurons hyperexcitable and vulnerable to degeneration. Notably, α -syn can directly perturb synaptic function: it associates with synaptic vesicle machinery and NMDA receptor subunits, altering neurotransmitter release and postsynaptic plasticity signaling [23]. This synaptic dysfunction can lead to early network dysregulation even before dopamine neurons die. For instance, extracellular α-syn oligomers have been shown to abnormally activate NMDA receptors, tipping the balance toward synaptic depression and hindering LTP induction [23]. Over time, α-syn-induced synaptic alterations may exacerbate firing irregularities and promote the cascade of circuit changes seen in PD. Additionally, as α-syn pathology spreads and dopamine cells are lost, the full spectrum of PD electrophysiology (bursting, oscillations, plasticity failure) becomes evident. Intriguingly, the α-syn overexpression model by Lobb et al. highlights that dopamine loss is requisite for the largescale oscillatory and firing alterations, since those transgenic mice did not manifest strong β oscillations or nigral burst firing until significant dopamine dysfunction occurred [24]. This underscores the view that α-synuclein pathology sets the stage (via synaptic and neuronal stress), but dopamine depletion is the tipping point that unleashes network-wide pathological activity.

In summary, electrophysiological hallmarks of PD - SNc neuron burst firing, exaggerated β oscillations in basal ganglia, and impaired cortico-striatal plasticity - have been consistently observed in rodent and primate models of dopamine depletion (6-OHDA, MPTP) and in α-synuclein models. These abnormalities provide insight into the circuit-level pathophysiology linking molecular disease processes to the motor symptoms of PD. Dopamine replacement or therapies targeting α-synuclein and synaptic health may therefore restore more normal firing patterns and synaptic plasticity, rebalancing the basal ganglia network. Continued research integrating toxin and genetic models will further clarify how dopamine and α-synuclein jointly drive these electrophysiological changes, guiding improved treatments for PD.

Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis and Huntington's Disease

Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: Hyperexcitability and Transmission Deficits

In ALS, an emerging electrophysiological hallmark is motor neuron hyperexcitability. Intrinsic electrical properties of motor neurons are altered such that they fire more readily than normal. For example, spinal motor neurons from superoxide dismutase (SOD1)-G93A mutant ALS mice (a familial ALS model) exhibit significantly increased firing rates in response to current injection, indicating elevated intrinsic excitability even before symptom onset [28]. This hyperexcitable phenotype has also been observed in patient-derived neurons and is thought to be a presymptomatic biomarker of ALS. Clinically, cortical hyperexcitability is detectable in ALS patients and even in presymptomatic carriers of ALS-causing mutations. Transcranial magnetic stimulation studies have shown that individuals carrying mutant SOD1 can display reduced cortical inhibition and heightened excitability well before weakness begins [29]. Such cortical disinhibition supports the "dying-forward" hypothesis, wherein upper motor neuron overactivity triggers downstream degeneration of lower motor neurons. Indeed, excitotoxic damage from hyperactive glutamatergic drive is proposed as one mechanism linking excitability to neuron loss [30].

Another key feature of ALS is altered synaptic transmission at the neuromuscular junction (NMJ). Even in early disease stages, motor nerve terminals show an impaired ability to sustain high-frequency firing. In SOD1-G93A mice, the most striking early deficit is a failure to maintain end-plate potential amplitudes during 20 Hz stimulation trains, appearing weeks before overt motor symptoms [31]. This suggests that neuromuscular transmission becomes functionally compromised prior to substantial motor endplate denervation. As the disease progresses, NMJ transmission deteriorates further - miniature EPP amplitudes and evoked responses eventually decline, culminating in the classic distal "dying-back" of motor nerve terminals. Notably, these early electrophysiological changes occur while motor axons and muscle endplates are still anatomically intact [31], highlighting functional impairment as a precursor to structural loss. Such findings underscore the potential of NMJ transmission metrics as early ALS biomarkers and therapeutic targets.

Mechanistically, the hyperexcitability and synaptic deficits in ALS models have been linked to the toxic biology of mutant SOD1 and transactive response DNA-binding protein-43 (TDP-43) proteins. Mutant SOD1 can disrupt ion channel function and astrocytic glutamate uptake, creating a hyperexcitable, glutamaterich environment that predisposes to excitotoxicity. Likewise, TDP-43 protein, which abnormally aggregates and mis localizes in most ALS cases, has been shown to induce cortical neuron hyperexcitability and synaptic dysfunction. In a TDP-43 transgenic mouse, mis localization of TDP-43 to the cytoplasm caused layer V pyramidal neurons in motor cortex to become intrinsically hyperactive, while their excitatory synaptic inputs were concurrently reduced in a compensatory response [32]. This TDP-43-driven cortical hyperexcitability mirrors the human disease and links aberrant TDP-43 aggregation to early electrophysiological disturbances. Overall, ALS is characterized by an excitation-inhibition imbalance in the motor system: excessive firing in upper and lower motor neurons and failing neuromuscular synapses. These electrophysiological abnormalities provide mechanistic insight into how mutant SOD1 or TDP-43 precipitate neuronal degeneration, and they offer quantifiable endpoints (e.g. cortical excitability, motor unit firing rates, NMJ synaptic fidelity) for tracking disease progression and therapeutic interventions.

Huntington's Disease: Striatal Circuit Dysfunction and E/I Imbalance

Huntington's disease primarily involves progressive degeneration of the striatum, and electrophysiological changes in striatal neurons serve as important biomarkers of dysfunction. The striatal medium-sized spiny neurons (MSNs) in HD models show early deviations in membrane and synaptic properties that precede neuron loss. In the fast-progressing R6/2 transgenic mouse (which expresses an exon 1 fragment of mutant huntingtin), MSNs become depolarized and hyperexcitable as the disease phenotype emerges. By the symptomatic stage, R6/2 MSNs have depolarized resting membrane potentials and increased input resistance, meaning they are more easily driven to fire [33]. Paradoxically, despite this intrinsic hyperexcitability, these neurons receive diminished effective excitatory drive from cortical afferents. Intracellular recordings reveal that larger stimuli are required to evoke synaptic responses in symptomatic R6/2 MSNs, and those excitatory postsynaptic potentials that do occur often have prolonged decay phases, indicating an excessive NMDA receptor component. This points to a deficit in normal corticostriatal synaptic transmission alongside abnormal NMDA receptor (NMDAR) signaling. Consistent with these findings, morphological studies show loss of dendritic spines on MSNs in R6/2 mice, reflecting the physical reduction of excitatory cortical inputs (since spines are the sites of glutamatergic synapses). Such synaptic pruning contributes to an early disconnection of cortex and striatum.

Notably, similar electrophysiological disturbances are observed in longer-term full-length mutant huntingtin models, underscoring that these changes are a fundamental consequence of the mutation rather than an artifact of the fragment model. MSNs in YAC128 mice (which carry the entire human mutant huntingtin gene) and in knock-in mice with ~140 CAG repeats develop the same core phenotype as R6/2 MSNs [34]. This includes a progressive increase in membrane input resistance and decreased membrane capacitance (signifying neuronal atrophy), along with a marked shift in synaptic balance: YAC128 MSNs show a lower frequency of spontaneous excitatory postsynaptic currents and a higher frequency of spontaneous inhibitory postsynaptic currents in certain cells. In other words, an excitation/inhibition imbalance arises in the striatal microcircuit, where glutamatergic input is functionally weakened while inhibitory GABAergic input (from interneurons or remaining MSNs) may be relatively enhanced. This imbalance can manifest as network-level dysrhythmias - for instance, juvenile-onset HD models often exhibit seizures or hyperkinetic movements, whereas later stages lead to overall circuit inhibition and bradykinesia. Electrophysiologically, the reduced corticostriatal excitation and increased inhibition impair the normal firing patterns of striatal output neurons, contributing to the motor and cognitive deficits seen in HD.

These synaptic and excitability changes are tightly linked to the pathogenic mutant huntingtin (mHTT) protein. mHTT aggregates in neurons and disrupts various cellular functions, including axonal transport of neurotrophic factors and the regulation of neurotransmitter receptors. Importantly, mHTT has been shown to alter glutamate signaling in a way that promotes neuronal injury. For example, studies in YAC128 mice found an increase in extrasynaptic NMDA receptor activity - an aberrant glutamate signaling mode that triggers pro-death pathways. This shift was evidenced by heightened NMDA currents outside of synapses accompanied by reduced activation of pro-survival CREB signaling [35]. The extrasynaptic NMDAR upregulation depends on mHTT proteolysis and is directly pathogenic, as its pharmacological inhibition (with low-dose memantine) can normalize signaling and improve neuronal function. Thus, the electrophysiological deficits in HD models provide mechanistic insight: mutant huntingtin disrupts the normal balance of synaptic excitation and inhibition in striatal circuits and renders neurons vulnerable to excitotoxic stress. Over time, this leads to diminished synaptic plasticity, loss of spines, and ultimately neuronal degeneration.

In summary, both ALS and HD exhibit distinctive yet analogous electrophysiological biomarkers - ALS is marked by hyperexcitability of motor neurons and failing neuromuscular synapses, while HD entails dysregulated excitatory/inhibitory synaptic function in the striatum. In each case, these electrical and synaptic abnormalities stem from the disease-defining protein aggregations (SOD1/TDP-43 in ALS, and mutant huntingtin in HD) and are intimately linked to the process of neurodegeneration. Tracking such electrophysiological changes in animal models (e.g. SOD1-G93A, TDP-43 transgenics, R6/2, YAC128) has shed light on disease mechanisms - for instance, revealing how neuronal hyperexcitability may drive excitotoxic motor neuron death in ALS, or how synaptic disconnection contributes to MSN vulnerability in HD. Importantly, these insights also suggest potential intervention points (such as modulation of neuronal excitability or synaptic receptors) that could help restore circuit stability and slow disease progression. The continued study of electrophysiological biomarkers in ALS and HD not only improves early diagnosis and monitoring but also enhances our understanding of the cascade from protein misfolding to neural network failure in these fatal neurodegenerative diseases.

Conclusion

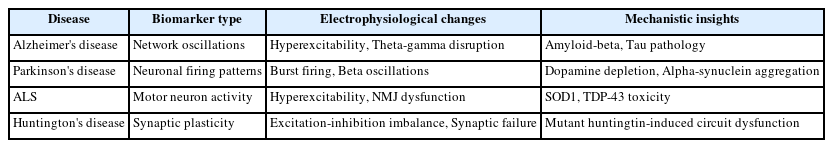

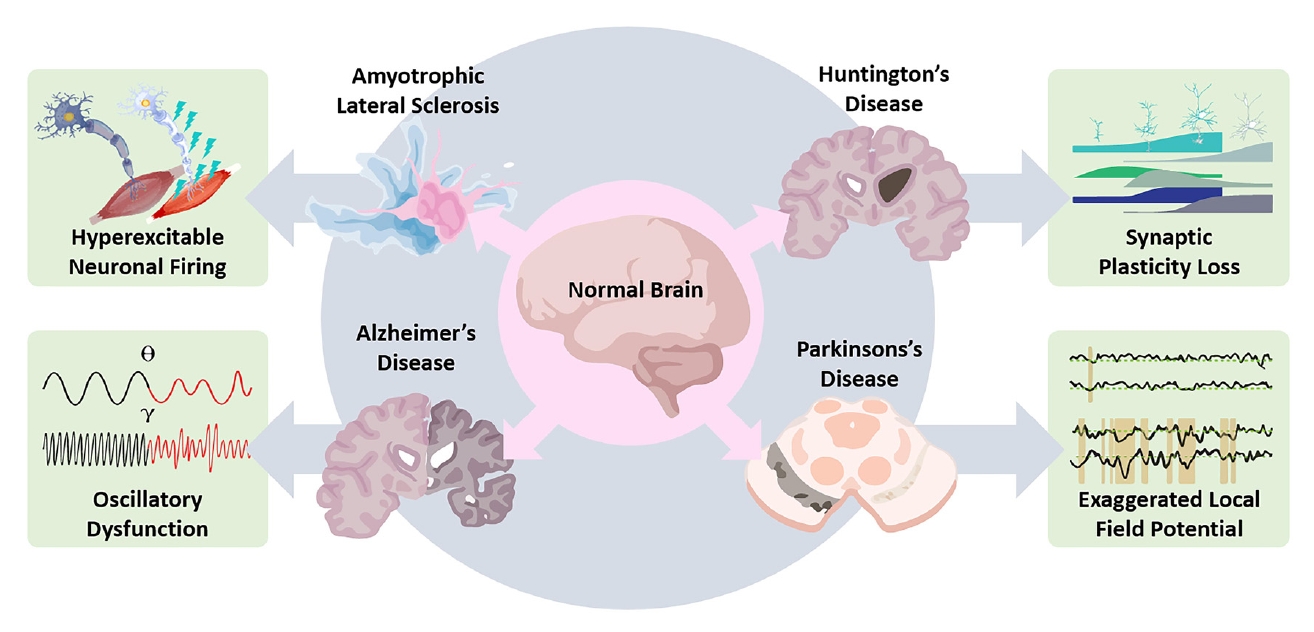

Electrophysiological biomarkers significantly enhance our understanding of the pathological mechanisms underlying neurodegenerative diseases, including AD, PD, ALS, and HD (Table 1, Figure 1). These biomarkers have proven invaluable in identifying early and subtle neural circuit dysfunctions before the onset of overt clinical symptoms or significant structural damage. Animal model studies have been instrumental in elucidating these electrophysiological alterations, providing detailed mechanistic insights into how abnormal neuronal activity, synaptic dysfunction, and disrupted neural oscillations contribute to disease progression. For instance, hippocampal hyperexcitability in AD, aberrant beta-band oscillations in PD, motor neuron hyperexcitability in ALS, and excitation-inhibition imbalance in HD all highlight specific pathological features that could serve as early diagnostic tools and therapeutic intervention points. Future research directions should focus on integrating these electrophysiological biomarkers with molecular and genetic data to develop comprehensive diagnostic and therapeutic strategies. Advancements in electrophysiological techniques and analytical tools will further enhance their clinical utility, potentially transforming patient management through earlier diagnosis, more accurate prognosis, and tailored therapeutic approaches, ultimately leading to improved outcomes and quality of life for individuals affected by these debilitating neurodegenerative conditions.

Notes

Funding

None.

Conflict of Interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Data Availability

None.

Author Contributions

All work was done by HSR.